Urgent message: Previously JUCM-published research revealed that even very low risk for a major adverse cardiac event left clinicians uncomfortable with discharging patients per 2018 ACEP guidelines. What can be learned from a follow-up study reflecting the updated version?

Rebekah Samuels, OMS-III; Francesca Cocchiarale; Samidha Dutta, DO, PGY-3; Jarryd Rivera, MD; Amal Mattu, MD; Michael Pallaci, DO; Paul Jhun, MD, FAAEM; Jeff Riddell, MD; Cameron Berg, MD; and Michael Weinstock, MD.

Citation: Samuels R, Cocchiarale F, Dutta S, Rivera J, Mattu A, Pallaci M, Jhun P, Riddell J, Berg C, Weinstock M. What is the acceptable miss rate for a major adverse cardiac event (MACE)? A follow-up survey after release of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) clinical policy on acute coronary syndromes. J Urgent Care Med. 2022;16(8):33-37.

ABSTRACT

Introduction

This study sought to characterize the acceptable miss rate among participants of the Essentials of Emergency Medicine conference in 2021 to determine if responses have changed since the publication of the 2018 chest pain guidelines of the American College of Emergency Physicians. A very low “acceptable miss rate” among clinicians results in unnecessary admissions and risk of patient harm from nosocomial infections, falls, false positive tests, unnecessary procedures, and expense.

Methods

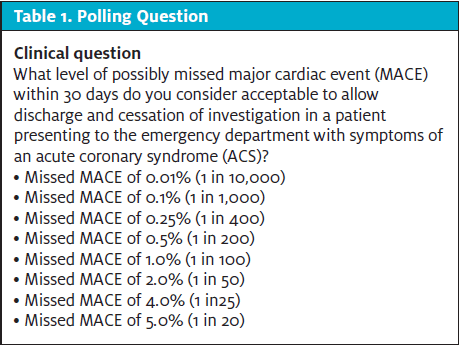

A survey was conducted during the Essentials of Emergency Medicine conference in 2021, the same conference at which the pilot survey was conducted in 2018. The 2021 survey consisted of one clinical and five demographic questions, identical to the 2018 pilot survey. The clinical question directly polled participants on what percent of possible MACE within 30 days they would be comfortable when discharging a patient presenting to the ED with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Results

Out of the 126 study participants, most were attending physicians (66.4%) with 0-5 years of clinical experience (37.1%). Nearly half of the participants practiced medicine in the United States, with the remaining participants practicing in Canada (18.7%), Australia (2.4%), United Kingdom (0.8%), and other countries (27.6%). Half of study participants reported an acceptable miss rate of 0.01% to 0.1%. Only 31% of participants were comfortable with a MACE rate of 1% to 2% as recommended by the 2018 ACEP guidelines.

Conclusion

Among a small international cohort of emergency medicine providers, a significant number of clinicians were not comfortable with the current ACEP guidelines regarding the acceptable miss rate for MACE, with only 50% comfortable with a miss rate of greater than 0.1% for MACE.

INTRODUCTION

In 2018, chest pain was the second most common presenting symptom to the emergency department, accounting for 5.5% of all encounters and totaling more than 7 million visits.1 Chest pain is also a common presentation to the urgent care, either as a primary complaint, or an associated complaint. Clinicians must investigate and triage these patients to avoid deadly consequences such as acute coronary syndrome (ACS), while also weighing the risks of false positive testing, costs of the evaluation, and the risks and benefits of admission. Unfortunately, even with thorough data gathering (history, exam, testing), ACS is occasionally not identified. Therefore, we must define an acceptable miss rate of ACS.

Patients presenting with possible cardiac symptoms are stratified into risk categories; the HEART score and EDACS pathway are two examples of clinical decision aides. The HEART score uses a scoring system based on history, ECG findings, age, risk factors, and troponin.2,3 With a low-risk HEART score (0-3), there is an expected 0.8%4 to 1.7%2 risk of major adverse cardiac event (MACE), defined as death, myocardial infarction, or revascularization in the following 4–6 weeks. With a low-risk score on the HEART pathway (two troponin tests), there is a 0.4% risk of MACE.3 With a low-risk score on EDACS,5 there is a 0.54% risk of MACE, based on a 2021 systematic review .6 Based on the risk, a disposition decision is made based on the recommendation of the clinician and/or with a process of shared decision making (SDM).

Without the ability to completely rule out the possibility of ACS, there is a possibility of a MACE even in low-risk patients.

The question What is an acceptable rate of MACE (major adverse cardiac event)? was presented to healthcare providers at the Essentials of Emergency Medicine conference in Las Vegas in 2018 and published previously, showing the majority of clinicians (47%) were only comfortable with rate of MACE less than 0.1%.7 This previous work was completed prior to the release of the 2018 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) clinical practice guidelines, which recommended a higher acceptable missed diagnosis rate of 1%–2% for a 30-day MACE in nSTEMI ACS.8

This study sought to characterize the acceptable miss rate among participants of the Essentials of Emergency Medicine conference in 2021 to determine if responses have changed since the publication of the 2018 ACEP chest pain guidelines.

METHODS

A survey was conducted during the Essentials of Emergency Medicine conference in 2021, the same conference at which the pilot survey was conducted in 2018.7 The conference is a 3-day event for continuing medical education credit that is certified by the American Medical Association for Physician’s Recognition Award Category. Due to social distancing, the 2021 conference was online only and had a total of 2,187 livestream attendees. The survey was available to all the attendees as a link on the conference app, which the conference attendees were asked to download.

The 2021 survey consisted of one clinical and five demographic questions identical to the 2018 pilot survey. All data were compiled into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Demographic questions covered professional role, practice setting, years of experience, primary work environment, and country of practice. The clinical question directly polled participants on what percent of possible MACE within 30 days they would be comfortable when discharging a patient presenting to the ED with symptoms of ACS (Figure 1). Descriptive statistics were calculated. This investigation received an “exempt” status by the Adena Health System IRB.

RESULTS

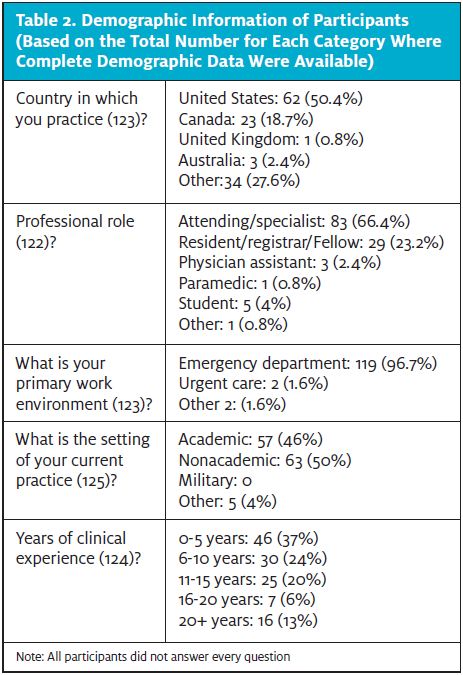

Out of the 126 study participants most were attending physicians (66.4%) with 0–5 years of clinical experience (37.1%). Nearly half of the participants practiced medicine in the United States, with the remaining participants practicing in Canada (18.7%), Australia (2.4%), United Kingdom (0.8%), and other countries (27.6%) (Table 2).

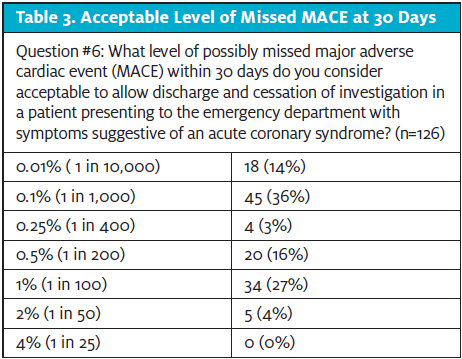

Half of study participants reported an acceptable miss rate of 0.01% to 0.1%. Only 31% of participants were comfortable with a MACE rate consistent with the 2018 ACEP guidelines of 1% to 2% (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The ACEP Clinical Policy states an acceptable missed rate of adverse cardiac events is 1% to 2%.8 In our 2021 study, which demographically had fewer participants from the United States but similar percentage of attending responses, we found that half of the surveyed participants only accept a missed MACE rate of 0.01% or 0.1%, 10-200 times lower than the 2018 recommended ACEP guideline. Furthermore, a similar 2018 study reported that nearly half of surveyed emergency medicine providers also accepted a missed rate of only 0.01%-0.1%.7 These results are both similar to the original study performed by Than, et al.9 The evident discrepancy of accepted rates between ACEP and practicing physicians poses a simple question: Why?

Though our study defines the acceptable miss rate and not the reasons for such a conservative approach in such a large percentage of clinicians, the risk of litigation can certainly play a decisive role in the influence of how physicians practice medicine. Over 90% of physicians believe that physicians order more tests due to fear of litigation.10 With missed MI being the leading cause of malpractice claims,11 it is not surprising that clinicians would want to minimize risk in patients with chest pain. However, a majority of MACEs—58% in Backus’s 2013 validation study—are revascularization procedures as opposed to death or MI.2

Admitting or sending a patient with low-risk chest pain to the ED is not without risk. In fact, there is a significant risk of a preventable adverse event with the very act of hospitalization.12 The majority of these adverse events are related to procedures and medications.13 A 2014 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 4% of patients had at least one hospital-acquired infection during their inpatient stay.14

Although missed MIs may pose medicolegal risk as well as a justified hospital stay, risk-stratification algorithms such as HEART and EDACS can greatly lower the risk of inappropriately discharging a patient home. Mahler, et al found that 0.4% of patients who were identified as low risk using the HEART score experienced death or an acute MI within 30 days.3 Use of the EDACS decision tool enables clinicians to discharge up to 55% of chest pain patients who were stratified as low risk.6

Did the recommendations for an acceptable miss rate from ACEP in 2018 change practice? With an identical survey being performed at the same conference both before and after the ACEP guidelines, we did not find any change in the acceptable miss rate of the clinicians who responded to this survey. The time it takes to translate findings from biomedical research to standardized patient care is up to 17 years.15 Our study was completed 3 years after the new acceptable missed MACE rate was published by ACEP in 2018.

LIMITATIONS

Our response rate is incalculable, as the survey was only available to those who downloaded the conference app, and those data are unavailable. It is possible that many of the 2,187 virtual attendees did not download the app and as such were not eligible to take the survey. That being said, the response rate was likely low, potentially reflecting a small sample pool including doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners that participated in the study. Over 50% of those who completed the survey were practitioners within the U.S., which presents more variability from the originally surveyed clinicians in 2018, but still only represents certain populations of emergency care.7

The low number of total responses, coupled with the responders all being attendees at a medical conference, may reflect selection bias and may limit the external validity of these findings. There was one respondent who did not answer all questions, but their identity was not able to be verified so the number of respondents in the demographic table and the answers to the question about MACE are not equal (of the 126 study participants, answers to all of the demographic questions include only 122 responses).

There are different tools used to define low-risk patients and risk of a major adverse cardiac event, such as HEART and EDACS. The HEART score is commonly utilized in the ED, but the lack of questions relating to other clinical decision support tools, including EDACS, may have limited the degree of clinicians’ ability to sort patients into definitive categories.

Though the answers to the actual question may be accurate, the wording of the question may serve to draw the participant to an incorrect conclusion; use of the word “missed” may imply litigation and poor practice16 and simply because MACE was missed, does not necessarily imply an adverse patient outcome.17

CONCLUSION

Among a small international cohort of emergency medicine providers, a significant number of clinicians were not comfortable with the current ACEP guidelines regarding the acceptable miss rate for a major adverse cardiac event, with only 50% comfortable with a miss rate of >0.1% for MACE.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2018-ed-web-tables-508.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2022.

- Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2153-2158.

- Mahler SA, Lenoir KM, Wells BJ, et al. Safely identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circulation. 2018;138(22):2456-2468.

- Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Aryal S, et al. HEART score risk stratification of low-risk chest pain patients in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(2):187-203.

- Than M, Flaws D, Sanders S, et al. Development and validation of the Emergency Department Assessment of Chest pain Score and 2 h accelerated diagnostic protocol. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(1):34-44.

- Boyle RSJ, Body R. The diagnostic accuracy of the Emergency Department Assessment of Chest Pain (EDACS) Score: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(4):433-441.

- Weinstock MB, Pallaci M, Mattu A, et al. Most clinicians are still not comfortable sending chest pain patients home with a very low risk of 30-day major adverse cardiac event (MACE). J Urgent Care Med. 2021;15(5):17-21.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Suspected Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes, Tomaszewski CA, Nestler D, Shah KH, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Emergency Department Patients with Suspected Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(5):e65-e106.