Published on

Urgent message: The goal for urgent care clinicians tasked with treating patients presenting with traumatic lacerations is rapid and cosmetic resolution of the injury. Using aseptic technique while repairing traumatic lacerations will minimize the risks of infections.

INTRODUCTION

Myriad advances in wound repair have emerged since the pioneer of antiseptic medicine, British surgeon Joseph Lister, transformed the field of surgery by incorporating his research in bacteriology and wound infections to improve patient outcomes. Today large variations and controversies in wound care treatment exist.1While manyurgent care centers utilize sterile, single-use laceration trays, with all the necessary supplies and instruments for performing minor surgical procedures, others assemble needed supplies and instruments individually wrapped.

The need for antibiotic therapy, delayed primary healing, healing by secondary intention, and referral to a wound-care center in severe cases may be avoided by using aseptic technique to reduce the risks of infection. To this end, all necessary steps should be taken to limit microbial contamination and avoid a prolonged healing process. Aseptic technique incorporates practices and procedures by medical staff to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs), an infection acquired as a result of treatment. Here, we re-examine the validity of evidence-based medicine components of aseptic technique in laceration repairs done in the urgent care setting.

BACKGROUND

As of the Urgent Care Association’s 2012 Benchmarking Report, laceration repair was the most common procedure done in an urgent care center.2 In the United States, 7 to 9 million lacerations treated annually account for approximately 8.2% of emergency department visits and 4% of urgent care center visits.3,4 The majority of lacerations presenting to urgent care centers result from traumatic encounters with dirty objects and surfaces. Common causes of lacerations with a high risk of infection are listed in Table 1. These lacerations require a more aggressive infection-prevention strategy such as the use of aseptic technique.

| Table 1. Common Causes of Lacerations Associated with Increased Risk of Infection ● Falls on dirty floors ● Table corner injuries ● Injuries from dirty tools/instruments/fishhooks ● Water exposure (ponds, lakes, rivers, ocean, swimming pools/hot tubs) ● Injuries during contact with sewage/mud ● Dog and cat bites ● Human bites ● Immunocompromised patients (eg, diabetes, HIV, medication-induced) ● Lacerations with dirt or particles embedded deep into the wound |

Intermediate and complex lacerations fall into this category. They may be very jagged, many layers deep, located over a joint, containing dirt or particles requiring extensive debridement and wound irrigation, or having a potential for nerve damage. Practicing aseptic technique is fundamental to decreasing the risks of infection, especially when treating high-risk lacerations. Lacerations repaired in an unsterile environment are at an increased risk for infection due to microbial contamination. Figure 1 highlights the case of a patient in her mid-40s who presented to the urgent care center as scheduled 10 days postrepair to have her thigh laceration sutures removed. This otherwise healthy patient was not diabetic, did not have HIV, renal failure, asplenia, or liver cirrhosis, nor was on medication-induced immunosuppression. The provider who performed the laceration repair used nonsterile gloves and did not practice aseptic technique. Treatment rendered at the postrepair visit included suture removal, 10 days of antibiotic therapy with sulfamethoxazole 800 mg-trimethoprim 160 mg bid, and the wound allowed to heal by secondary intention. Although the scar once fully healed did not impair function or cause physical discomfort, it resulted in a disfiguring hypertrophic scar. An important goal in laceration repair must include a good cosmetic result.5

Figure 1. Image of infected thigh laceration repair in which aseptic technique was not used. Red arrows show sites of purulent drainage prior to cleaning the wound. Green arrows show reddish areas indicating spreading cellulitis. Image courtesy of Oscar D. Almeida, Jr., MD, FACOG, FACS.

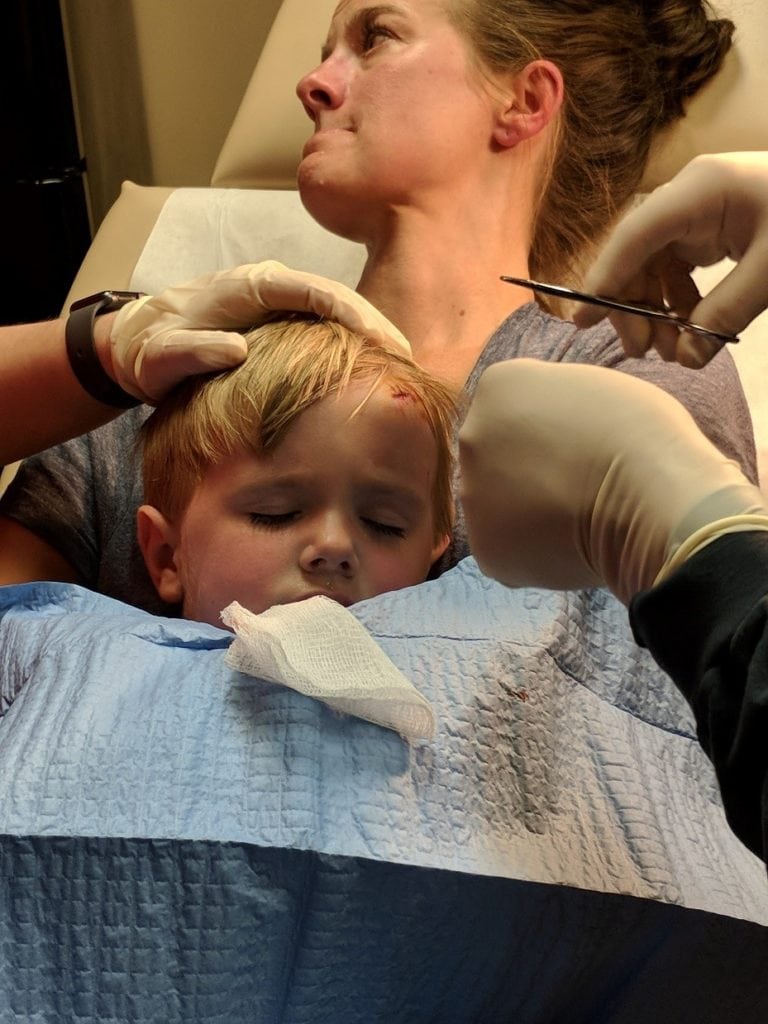

Maintaining a sterile field while the urgent care provider repairs traumatic lacerations in young children can be challenging. Since head and neck wounds account for the majority of pediatric lacerations, using aseptic technique in these procedures will minimize the risks of infection. Employing the parental papoose technique in children under the age of 6 years may provide an added level of comfort to the child while laying on their parent’s lap during the laceration repair.6 The additional cooperation by the child will minimize uncontrolled movements which can compromise the sterile field. Figure 2 illustrates use of the Parental Papoose Technique while maintaining a sterile field in a young child laying on his mother’s lap having his forehead laceration repaired.

Figure 2. Maintaining a sterile field using the parental papoose technique.Image courtesy of Oscar D. Almeida, Jr., MD, FACOG, FACS.

AREAS OF ASEPTIC TECHNIQUE CONTROVERSY

Sterile vs Nonsterile Gloves

This is the most controversial component of aseptic technique. Generally, nonsterile gloves are used for nonsurgical medical procedures and examinations. One of the main differences between sterile and nonsterile gloves is the acceptable quality level (AQL) of pinholes, indicating the percentage of gloves in the sample that will have pinholes in them. Sterile gloves have a lower AQL than nonsterile gloves. Because of this, nonsterile gloves should be considered a potential extrinsic infectious foci because they cannot provide an impenetrable barrier between the patient and healthcare provider7who may not have practiced appropriate hand hygiene.

A laboratory-based study of nonsterile gloves in patient rooms found that 75% of gloves sampled were contaminated with at least 1 species of bacteria, most commonly coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, diphtheroids, and Micrococcus species.8Interestingly, bacteria were not recovered on gloves from a newly opened box. This is significant because unless a new box of nonsterile gloves is opened for each laceration repair procedure, the potential risk for dirty gloves in an urgent care procedure room is high. Unlike hospital and outpatient operating rooms, urgent care procedure rooms are not thoroughly cleaned and disinfected according to Joint Commission standards following each procedure.

One study of more complicated skin surgery procedures conducted by private dermatologists examined infection rates and found a higher rate of infection when procedures were done with nonsterile gloves (14.7%) instead of sterile gloves (3.4%) (P<0.001).9Superficial suppuration accounted for 94% of the surgical site infections, with 5.9% progressing to abscess formation. These findings support the preferred use of sterile gloves for the majority of intermediate and complex lacerations treated in the urgent care center.

An extensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials comparing infection rates from procedures limited to oral surgery, Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, standard incisions, and simple laceration repairs concluded that sterile gloves were not superior to nonsterile gloves.10However, not every trial was a randomized controlled trial and the inclusion of observational studies increased the risk of bias. More importantly, other extensive surgeries and complicated laceration repairs were excluded, calling into question the applicability of these findings for the urgent care centers since many traumatic lacerations treated in these facilities are extensive and contaminated.

The main attraction for the use of nonsterile gloves for laceration repairs appear to be the decreased glove cost. Perhaps it would be prudent to have a procedure room drawer exclusively designated for nonsterile gloves to be used for simple laceration repairs. This would prevent the provider from using nonsterile gloves that have been exposed to fomites in sick patient care areas.

Handwashing

Although gloves are routinely worn during repair of lacerations, they are not by themselves a substitute for hand hygiene in preventing infections. Regrettably, routine handwashing prior to procedures is inconsistent. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, healthcare providers wash their hands less than half of the times they should.11One study noted that the rate of compliance with hand hygiene was found to be significantly lower when gloves are worn.12

Potential glove leaks underscore the need for proper handwashing to prevent infections before donning gloves for a procedure. Albin, et al found significantly high latex surgical glove leak rates following surgical and dental procedures.13In the event of a glove perforation during a procedure, the risk for infection will be minimized if the hands are properly washed beforehand.

Tap Water vs Sterile Water for Wound Irrigation

By achieving dilution of the microbial load, wound cleansing is one of the most important components and should be the first step taken in preventing subsequent laceration infections. Overall, tap water has been evaluated and found to be safe for wound cleansing. A Cochrane review concluded that compared with sterile saline, wound cleansing with tap water was found to be statistically as safe for prevention of subsequent infection.14For example, when a construction worker with a laceration presents to the urgent care center, it is prudent to have them thoroughly wash the wound with soap and water.

However, it is noteworthy to mention that clear water does not necessarily equate to safe water.15 Contamination of potable water can occur under several circumstances including natural disasters such as hurricanes and flooding, accidental spillage of waste, urbanization, or damage to infrastructure. If there is any concern regarding the quality of tap water, sterile saline is always the safe bet.

Pearls

- Don’t use open-box nonsterile gloves that have been laying in patient care areas for laceration repairs, as they may have been collecting fomites.

- Unless you are confident of the tap water quality, use sterile saline for wound irrigation. Many of us at times have seen rust or other particles in tap water.

- Always practice good hand hygiene prior to donning gloves.

- Individualize your aesthetic technique according to the degree of risk for infection. Infection risk is lower in simple, clean, superficial lacerations.

- A postprocedure infection can impact healing and cause scarring. Wounds that become infected generally have a worse cosmetic result.

CONCLUSION

Aseptic technique is a fundamental component in the strategy to prevent postlaceration repair infections. In low-risk cases such as simple, superficial clean lacerations, clean nonsterile gloves may be used with minimal risk of infection. A consistent hand hygiene policy should be mandated and followed in all urgent care centers. Our goal should always include a satisfactory cosmetic result.

REFERENCES

- Ubbink DT, Brolmann FE, Go P, Vermeulen H. Evidence-based care of acute wounds: a perspective. Adv Wound Care(new Rochelle). 2015;4(5):286-294.

- Urgent Care Association of America. 2012 Urgent Care Benchmarking Results. Available at: http://www.ucaoa.org. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Singer AJ, Thode HC, Jr, Hollander JE. National trends in ED lacerations between 1992 and 2002. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:183-188.

- Weinick R, Burns R, Mehrotra A. How many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics? Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1630-1636.

- Almeida OD Jr. Repair of split earlobe lacerations in the urgent care. J Urgent Care Med. August 2019. Available at: https://www.jucm.com/repair-of-split-earlobe-lacerations-in-the-urgent-care/. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Almeida OD Jr. Employing the parental papoose technique in treating young children. J Urgent Care Med. 2018;13(1):26-29.

- Hebl JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med.2006;31(4):311-323.

- Diaz MH, Silkaitis C, Malczynski M, et al. Contamination of examination gloves in patient rooms and implications for transmission of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(1):63-65.

- Rogues AM, Lasheras A, Amici JM, et al. Infection control practices and infectious complications in dermatological surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65:258-263.

- Castelli G, Friedlander MP. The (sterile) gloves are coming off. Clin Rev.2018;28(9):e1-e2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. Available at: http//:www.cdc.gov/handhygiene. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Fuller C, Savage K, Besser S, et al. The dirty hand in the glove: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

- Albin MS, Bunegin L, Duke ES, et al. Anatomy of a defective barrier: sequential glove leak detection in a surgical and dental environment. Crit Care Med.1992;20(2):170-184.

- Fernandez R, Griffiths R. Water for wound cleansing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD003861.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Housing Reference Manual. Chapter 8 – Rural water supplies and water quality issues. Available at: https://cdc.gov/nceh/publications/books/housing/cha08.htm. Accessed September 25, 2020.

Oscar D. Almeida, Jr., MD, FACOG, FACS is a staff physician at Urgent Medcare Medical Center in Huntsville, AL and a former adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of South Alabama College of Medicine. Dr. Almeida has been an invited faculty for the Urgent Care Association Wound Care Workshops.