Published on

Differential Diagnosis

- ST-Elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Hyperkalemia

- Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and rate-related right bundle branch block (RBBB)

- Atrial fibrillation with pre-excitation (Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome)

Diagnosis

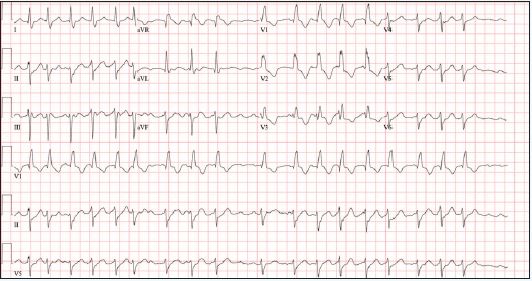

The repeat ECG (Figure 2) reveals atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response at a rate of 132 beats per minute. There is a left axis deviation and a wide QRS with rSR’ in V1-V3 and a broad, slurred S-waves laterally—consistent with RBBB. There are no ST deviations. When comparing with the prior ECG, the RBBB is new.

The current conceptual understanding of the trifascicular framework of the intraventricular conduction system derives from a series of seminal papers by Rosenbaum, et al from 1969 to 1973. These works elucidated three conduction terminals—one in the right ventricle (the right bundle) and two in the left ventricle (the anterior and posterior divisions of the left bundle).1-3

Conduction disturbances of any or all three conduction terminals may result from structural abnormalities of the His-Purkinje system caused by necrosis, fibrosis, calcification, infiltrative disease, electrolyte disturbances, or impaired vascular supply.4

Rate-related bundle branch blocks were first described in the mid-20th century. In most cases, rate-related bundle branch blocks occur due to a prolonged refractory period of a diseased bundle. When a critical heart rate is exceeded, the diseased bundle fails.5,6

Rate-related bundle branch blocks can be especially challenging to diagnose when the rate is regular and fast (eg, supraventricular tachycardia), creating a regular, wide complex tachycardia that appears like ventricular tachycardia. The irregularly irregular rhythm makes ventricular tachycardia unlikely and favors atrial fibrillation. There is no evidence of ST-elevation or findings of hyperkalemia (eg, peaked T waves). Atrial fibrillation with pre-excitation (ie, Wolf-Parkinson-White) characteristically produces a rate that exceeds 250 bpm at times and has variable QRS morphologies, neither of which is present in this ECG.

Clinical relevance

Syncope is a transient, self-limited loss of consciousness and postural tone, followed by spontaneous recovery back to baseline. It is a common chief complaint in the urgent care environment. While the underlying cause is not often determined in the urgent care setting, it is important to rule out severe or life-threatening etiologies of syncope. This is best done by a thorough history and physical exam, and careful examination of the ECG.

Cardiac arrhythmias are an extremely important consideration when evaluating a patient with syncope. This patient initially presented in sinus rhythm with a left anterior fascicular block. However, she became symptomatic when she was in atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and demonstrated a new, rate-related RBBB. These ECGs together demonstrate significant underlying conduction disease (ie, RBBB, left anterior fascicular block). This patient should be evaluated by a cardiologist/electrophysiologist urgently.

Learnings/What to Look for

- Right bundle branch blocks can be identified by a QRS >120 msec, rSR’ in V1-V3, and a broad, slurred S-wave in the lateral leads (I, aVL, V5, and V6)

- Left anterior fascicular blocks can be identified by left axis deviation, rS complexes in leads II, III, aVF (small R waves and deep S waves), qR complexes in leads I, aVL, (small Q waves and tall R waves)

- Rate-related bundle branch blocks happen when a diseased bundle encounters a critical rate

- Patients with significant conduction disease are at higher risk of dysrhythmias

Pearls for initial management:

- All patients with syncope should receive an ECG

- Utilize the clinical history and exam in tandem with the ECG to identify the etiology of syncope

- Syncope presumed secondary to cardiac arrhythmia should be transferred to a facility with cardiology capabilities

REFERENCES

- Rosenbaum MB. The hemiblocks: diagnostic criteria and clinical significance. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1970;39(12):141-146.

- Rosenbaum MB, Elizari M V, Lazzari JO, et al. Intraventricular trifascicular blocks. Review of the literature and classification. Am Heart J. 1969;78(4):450-459.

- Elizari M V, Acunzo RS, Ferreiro M. Hemiblocks revisited. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1154-1163.

- Surawicz B, Childers R, Deal BJ, Gettes LS. AHA/ACCF/HRS Recommendations for the Standardization and Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram. Part III: Intraventricular Conduction Disturbances a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(11):992-1002.

- Bauer GE. Bundle branch block under voluntary control. Br Heart J. 1964;26:167-179.

- Vessel H. Critical rates in ventricular conduction: unstable bundle branch block. Am J Med Sci. 1952;44(6):830-842.