Shoulder Pain in a Young Male

Urgent message: Traumatic injury isn’t the only factor to be weighed in patients with subluxation.

Author: Ralph S. Bovard, MD

Author Information: Ralph S. Bovard, MD, is a staff physician in the Department of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine, University of Minnesota Physicians, Minneapolis, MN.

Case Presentation

An 18-year-old male presented to the clinic with a complaint of left shoulder pain. He had been riding on a metro bus a week earlier when it turned suddenly, throwing him against the side of the vehicle. He stated that he had immediate discomfort in the affected shoulder that had persisted to the current time. The patient described the pain as an aching, continuous discomfort. He had ongoing difficulty with lifting the left arm and decreased motion due to pain. He was contemplating a lawsuit against the metropolitan bus service.

Observations and Findings

ROS: Not sleeping well

ALLERGIES: None

SURGERIES: None

FAMILY HISTORY: Type II diabetes, heart disease, and elevated cholesterol

MEDICATIONS: Ibuprofen for pain

Physical Exam

Morbidly obese male: Height 5′ 11″, weight 463 lb, BMI 64.6 kg/m2.

The patient was AOx3 with normal respirations. Despite the radiographic appearance, he did not hold his left arm in a fixed position or evidence the discomfort normally seen with a frank glenohumeral (GH) shoulder dislocation. He had pain with attempts to actively elevate the left arm above 45 degrees in forward flexion or abduction. He had pain with attempts to thumb-down abduct in the line of scaption above 45 degrees. With the elbow adducted to the side, however, he strongly resisted external rotation and internal rotation. While lying supine on the exam table, the patient tolerated passive abduction to 90 degrees with external rotation to 75 degrees and internal rotation to 60 degrees. He did have a positive apprehension sign and an equivocal relocation sign.

Neurovascular function was intact to the left arm and hand. Specifically there was normal sensation in the axillary and musculocutaneous nerve distributions. The patient had normal range of motion at the elbow and wrist. His grip strength was >100 lb with the injured left hand and 125 lb with the dominant right hand.

Diagnostic Studies

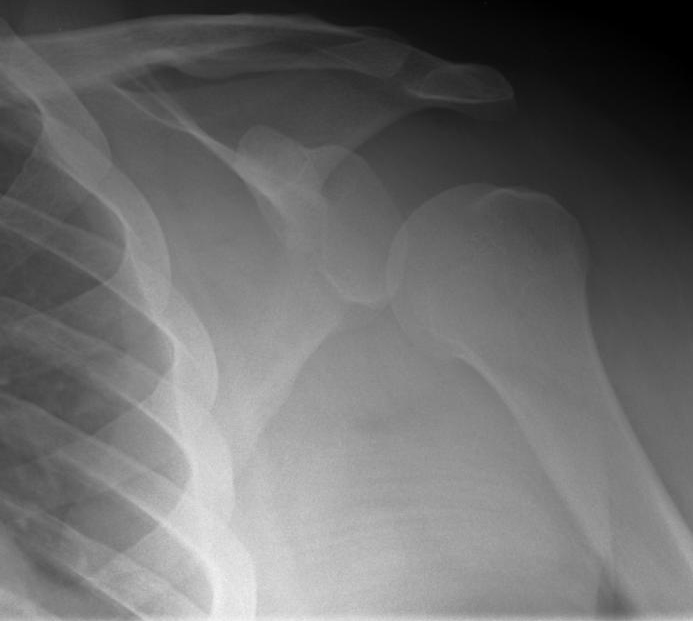

No lab tests were ordered. Three x-rays of the left shoulder, including the AP view in Figure 1, were obtained.

FIGURE 1

The AP and Y-views demonstrated an inferiorly displaced humeral head with respect to the glenoid socket. The subacromial space, normally ~10 mm, was greater than 25 mm. The axillary view was difficult to interpret due to soft tissue interposition. There was no evidence of a Hill Sachs lesion or a bony Bankart lesion. The findings were consistent with a glenohumeral subluxation or possible “perching” inferior-posterior partial dislocation.

Magnetic resonance imaging was obtained, which was normal. The humeral head was clearly demonstrated to be positioned anatomically relative to the glenoid fossa.

There was no evidence of injury or inflammation to the supraspinatus, subscapularis, or infraspinatus cuff tendons. The labrum appeared normal. There were no Hill-Sachs or soft tissue Bankart lesions.

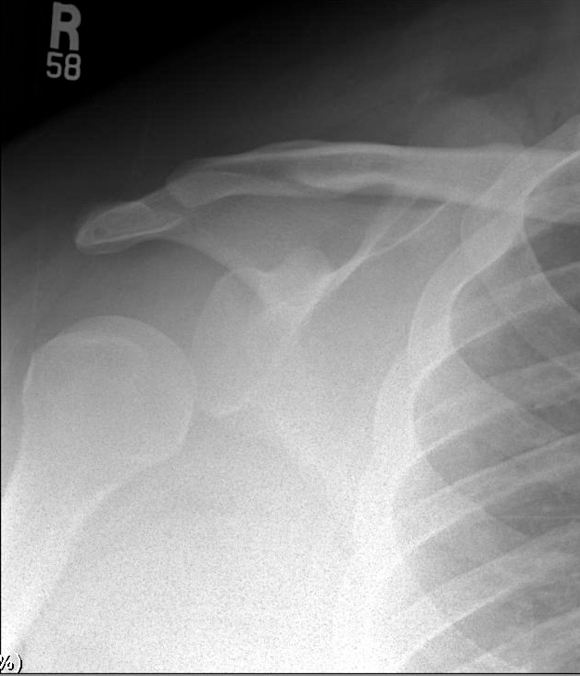

At the follow-up visit we obtained x-rays of the uninjured right shoulder (Figure 2) which demonstrated inferior subluxation of the humeral head relative to the glenoid fossa.

FIGURE 2

Diagnosis

The patient’s findings were consistent with bilateral inferiorly subluxed humeral heads due to the excessive weight of his arms. This was felt to be an overload rather than a traumatic injury process.

Course and Treatment

No attempt was made to “relocate” or “reduce” the GH subluxation/dislocation at the initial visit*. A physical therapy referral was completed for the patient with the aim of strengthening the rotator cuff and shoulder musculature. He was encouraged to initiate a weight loss program. No injections or surgical remedies were advised.

General Discussion

The patient’s findings were consistent with bilateral inferior displacement of humeral heads relative to the glenoid. This GH subluxation appeared to be due to the size and weight of the patient’s arms. Suboptimal muscle stabilization in concert with global stretching of the GH capsular ligaments would be necessary to allow this to occur. It should be noted that the x-rays were obtained with the patient upright with his arm in a dependent position subject to the forces of gravity. The MRI was obtained with the patient lying supine on the gantry for image acquisition. In the recumbent position the GH joint subluxation then spontaneously reduced.

In true recurrent traumatic injuries to the GH joint the findings are classically Traumatic, Uni-lateral (and uni-directional), a Bankart lesion (soft tissue and/or bony) is often present, and Surgery is the indicated remedy. The acronym TUBS is used to describe this phenomenon. Congenital laxity of the joint, seen more frequently in females, is typically Atraumatic, Multidirectional, Bilateral, and Rehabilitation rather than surgery is preferable, but if surgery is indicated, an Inferior capsular shift may be indicated. AMBRI is the acronym for this condition.

The distinction between traumatic and atraumatic shoulder instability has been recognized since Hippocrates. Neer presciently added a third category which he termed “acquired instability.” Such patients lack a history of true traumatic injury nor do they have any underlying collagen disorder causing generalized laxity. Rather, repetitive microtrauma leads to an enlarged joint capsule, as seems to be the situation in this young man’s case.

*The author was a ski clinic physician and, over the course of 3 years, reduced ~90 dislocations. This patient’s injury was recognized as atypical at the time of the initial clinical exam.