URGENT MESSAGE: Unlike most retail and service businesses in which customer transactions result in immediate cash in the register, the nature of insurance and government billing in urgent care creates accounts receivable, which can be a complicating factor when buying or selling an urgent care practice.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc is Practice Management Editor of JUCM—The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine, a member of the Board of Directors of the Urgent Care Association of America, and Vice President of Strategic Initiatives for Practice Velocity.

When a hospital, private equity, or medical group acquires an urgent care center, they can structure the transaction as an acquisition of the entire business—including assumption of the seller’s contracts and liabilities—or it can buy selected assets such as the seller’s name and goodwill or furnishings, fixtures, and equipment; assume specific obligations of the seller such as leases; and/or purchase the seller’s accounts receivable.

Accounts receivable constitute money owed to a business. When an urgent care center treats a patient, it will book the visit price as revenue, but also as a “receivable” because it is still owed money. In our industry, accounts receivable consist of billings to government benefit administrators and private insurance companies for patient visits, billings to employers for services like drug screens and physicals, and billings to patients for balances not paid by insurance. Accounts receivable are considered an asset owned by the business, with the economic “value” being the future cash generated as payments are received; these can then be used to cover operating expenses, capital investments, and distributions to the owners.

A big issue with accounts receivable—vs a pure cash business—is that revenue is rarely equal to the price of services provided. The difference between billings and what a third-party payer approves is written off as the “contractual allowance.” Balances owed to the center but not paid are written off as “bad debt.” Depending on the center’s fees relative to its contracts, actual cash collections can be a fraction of the price of services provided.

The collectability of all receivables is not equal. Some payers, such as state Medicaid programs, have a reputation for “low rate” but “fast and reliable” pay. Commercial insurance companies are known to mark down medical bills to what the contract will cover, to deny claims if coding rules are not followed, or to require supporting documentation such as a copy of the chart before paying a claim.

With private insurance shifting to high-deductible plans and raising copays and co-insurance, increasingly patients who present an insurance card are personally responsible for the entire cost of their visits. If an urgent care center does not correctly assess and collect this patient responsibility at the time of service, time is lost billing and through the process of receiving a “zero” Explanation of Benefits from the insurance company then trying to collect directly from the patient. Collections rates on patient financial responsibility after the fact can be low.

When evaluating an urgent care practice for purchase, the buyer must be able to accurately place a value on the accounts receivable, which includes understanding how long ago the services were rendered (aging), who the balances are owed from, and historic collections rates on those types of accounts, as well as billings/collections practices ranging from benefits verification, front-end collection of patient responsibility, billing system capabilities, and staffing and workflow in the billing department. This evaluation can require significant due-diligence; otherwise, if the buyer’s collections rates fall short of what’s anticipated, the buyer would have overpaid for the practice (diluting its return on its investment) and/or the seller could forego some payment of past services rendered.

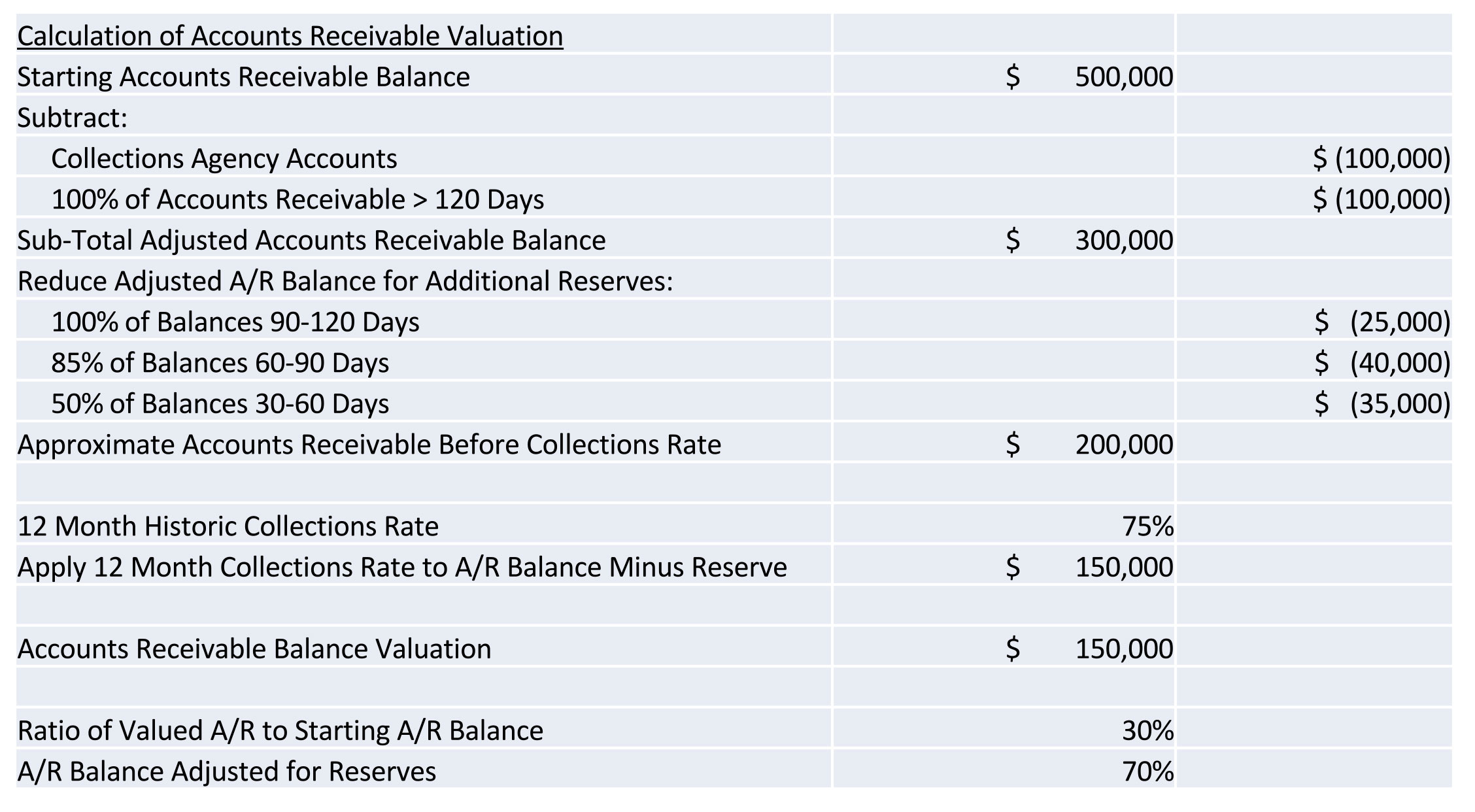

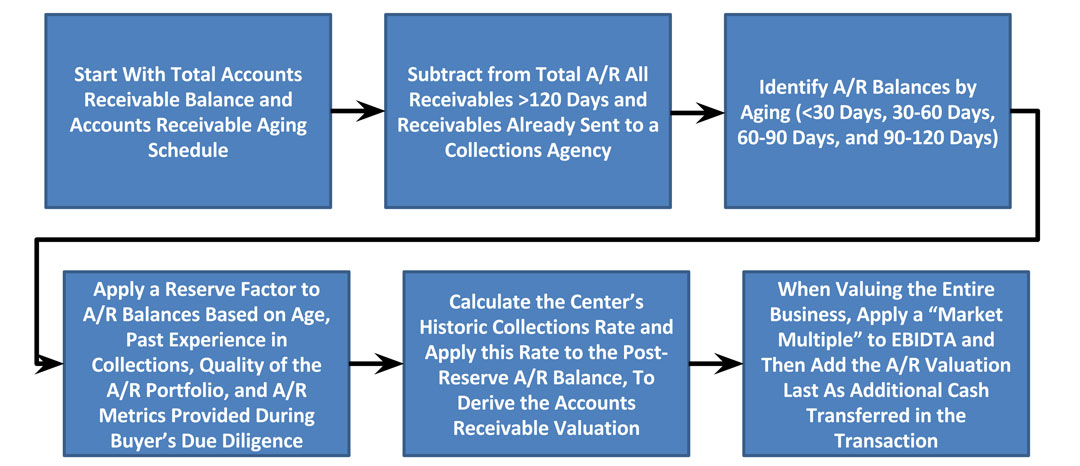

Figures 1.0 and 2.0 illustrate how to value accounts receivable when acquiring an urgent care practice.

Figure 1.0: Calculation of Accounts Receivable Valuation

Valuation of accounts receivable entails adjusting the current A/R balance by the expected rate of collections depending on the age of receivables. For example, receivables already in collections and those greater than 120 days are generally deemed “uncollectable” and thus excluded from valuation. Balances under 120 days are reduced by a “reserve” risk that the balances are uncollectable. The practice’s historic collections rate is then applied to the adjusted A/R balance.

Figure 2.0: Process Illustration of Valuing Accounts Receivable

The following process diagram details the steps followed to derive the adjusted accounts receivable balance in Figure 1.0

In addition to correctly valuing receivables, the following issues must be considered by both buyers and sellers:

- Legal: Can an acquiring practice bill the seller’s accounts receivable using the buyer’s tax ID? Are the buyer’s contracts with third-party payers at the same terms as the seller’s, or would the buyer have to somehow assume the seller’s contracts? Such would change the deal from an asset purchase to a purchase/integration of legal entities, which adds additional layers of legal work and could expose the buyer to additional unwanted liabilities of the seller.

- Systems: If the buyer and seller are on different billing platforms, the buyer may have to migrate the seller’s data to the buyer’s system, which could entail significant IT consulting expense. The buyer would have to consider this expense in calculating a value for the seller’s practice. Otherwise the buyer’s team would have to implement, learn, and support two billing platforms. Often, the buyer will continue to use the seller’s system and the seller’s billing employees for a period of time after the sale, which not only delays integration of the acquired practice but means additional costs (eg, software licensing fees and retention payments for the seller’s staff). Maintaining two systems creates additional work throughout the buyer’s organization. For example, the accounting department’s month-end financial reconciliation is complicated by adding another system that must be “locked down” at each month-end close.

- Personnel: Most billing departments embedded in urgent care operations (not third-party billing companies) are not set up to be collections agencies for others’ receivables, so the buyer’s billing team would have to look at resources, workflow, etc., detracting from its current focus collecting for the business it runs today. The acquiring practice may have to retain the billing team from the acquired practice—with significant retention bonuses paid—changing the economics of the deal.

- Costs: Collection of accounts receivable adds costs in addition to systems and personnel, such as clearinghouse fees for electronic claim submissions, rendering fees for paper statements, postage, phone calls, secondary insurance submission, and communication time with payers and patients. In addition to correctly valuing the seller’s receivables according to aging, type, and performance, a buyer must also consider its direct and indirect costs in collecting the receivables and adjust the valuation accordingly.

- Policies: Differences between the buyer’s and seller’s billing and collections policies affect not only collections rates, but also patient experiences and perceptions. Medical billing organizations typically manage their unpaid receivables internally for approximately 90 to 120 days, during which all third-party payment issues are resolved and the remaining patient financial responsibility is determined. After three attempts at collecting from patients, the practice typically turns over any unpaid patient balances to an outside collections agency who may ultimately “ding” an unpaying patient’s credit rating. If the seller’s patients are used to paying only a copay at time of service and being billed for any deductibles; if the seller has continued to treat patients with outstanding balances; or if the seller writes off uncollectable debt vs sending it to external collections, new policies to the contrary may improve collection rates for the buyer but risk alienating patients, ultimately affecting the center’s volume.

- Financing: The buyer may be limited in what it can pay for a practice, or lenders may be hesitant to allocate money in funding agreements to purchase accounts receivable. Lenders may argue that buying accounts receivable, which has some unknown characteristics, increases its risk. On the other hand, having an immediate stream of cash flow from receivables could help a buyer make its debt service and provide working capital for the acquired operation.

If a buyer chooses not to acquire the accounts receivable, the seller will have to collect on remaining balances. Sellers prefer transactions that provide a clean ending, so with accounts receivable included in the sale, all payments coming into the center or through the mail belong to the buyer. Most banks will accept documentation from the purchase agreements or bill of sale, enabling the buyer to deposit checks made payable to the seller.

In addition, “seamless” transition should be considered from the patient’s perspective. It’s much easier for patients to continue to do business with the urgent care center as they always have, as opposed to having to differentiate bills sent from the seller and buyer. Acquiring accounts receivables also provides the buyer an opportunity to communicate with past patients about the practice transition, helping retain those patients under the new ownership.

The biggest reason for an urgent care buyer to forego acquiring accounts receivable is inability to reach agreement on valuation. However, every transaction is unique and it’s the duty of all parties involved in a transaction—brokers, attorneys, accountants, and consultants—to make sure all aspects of the transaction are reviewed competently and executed successfully, regardless of whether the receivables are included.