Brad Laymon, PA, CPC, CEMC

Over my career as a physician assistant, I have delved extensively into the intricacies of medical coding guidelines. Through collaborative initiatives with healthcare systems and fellow clinicians, I have been able to identify 9 common, recurring coding pitfalls. This process came with significant time and experience, and I want to share what I’ve learned as my ultimate objective has always been advancing charting accuracy to instill confidence among providers in their coding practices.

1. Failure to ‘Diagnose’ Abnormal Vital Signs

Generally, it’s best to add abnormal vital signs as a separate diagnosis if they are not part of a primary diagnosis, but this is a practice I’ve rarely observed among my colleagues. This confirms that the abnormal vital has been identified and appreciated. For example, unexplained tachycardia can be added as a diagnosis with the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) code R00.0, “tachycardia, unspecified.”1 Similarly, any patient whose blood pressure (BP) is elevated while in the urgent care (UC) center can have that vital sign abnormality added as a diagnosis. If they have a history of hypertension, then you have met the criteria for a chronic illness with exacerbation. If they do not have a history of hypertension, elevated BP could be added as a diagnosis with a plan for managing the elevated BP (ICD-10 code R03.0). Adding such diagnoses better capture the complexity of the patients we care for.2

2. Failure to Identify a Chronic Illness with Exacerbation

The occurrence of exacerbations of chronic illness are frequent causes for patient encounters in urgent care. From a medical coding perspective, a chronic condition is deemed poorly controlled if it fulfills specified criteria and the patient does not achieve treatment goals.

Consider the following examples:

- A 67-year-old male with a complaint of “a chronic back pain flare up” arrives in the UC. He denies any injury but states it started after raking the back yard for about 45 minutes. He takes meloxicam 7.5 milligrams as needed for this chronic condition.

- A 34-year-old female complains of an asthma attack. She has used her albuterol inhaler with little relief. She denies any recent upper respiratory infection.

- A 59-year-old male patient is being seen for a sore throat, but his blood pressure is 168/97. He does have a history of hypertension (HTN). He is prescribed hydrochlorothiazide 25 milligrams daily.

What do these patient complaints have in common? They all have chronic illnesses that are exacerbated and/or poorly controlled.

Let’s look at the possible ways in which UC clinicians might address or manage these 3 examples:

- The 67-year-old male with chronic back pain will start taking acetaminophen 1000 milligrams every 8 hours scheduled as well as his meloxicam 7.5 milligrams once daily instead of using it as needed for the next 5-7 days.

- The 34-year-old female with the asthma attack was given 1 albuterol nebulizer treatment in the center with improvement in her breathing. She will continue her albuterol inhaler at 2 puffs every 4-6 hours as needed and start a short course of oral prednisone.

- The 59-year-old male patient who is being seen for a sore throat has a blood pressure reading of 168/97. The clinicians has a discussion about his elevated blood pressure during the visit. He reveals that he is not taking his hydrochlorothiazide as prescribed. He will resume his hydrochlorothiazide 25 milligrams once daily, monitor his BP daily at home, and see his primary care provider for further evaluation/treatment.

What level of service would you code the above examples? The correct level of service—with proper documentation—would be level 4 for all the above visits.

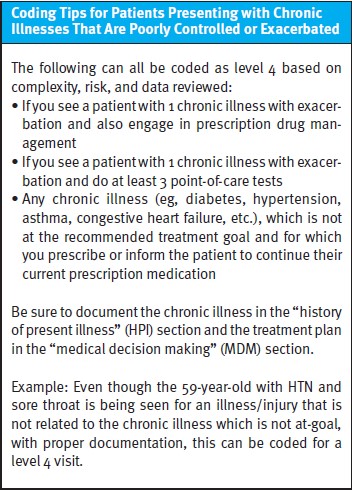

Coding Tips for Patients Presenting with Chronic Illnesses That Are Poorly Controlled or Exacerbated

The following can all be coded as level 4 based on complexity, risk, and data reviewed:

- If you see a patient with 1 chronic illness with exacerbation and also engage in prescription drug management

- If you see a patient with 1 chronic illness with exacerbation and do at least 3 point-of-care tests

- Any chronic illness (eg, diabetes, hypertension, asthma, congestive heart failure, etc.), which is not at the recommended treatment goal and for which you prescribe or inform the patient to continue their current prescription medication

Be sure to document the chronic illness in the “history of present illness” (HPI) section and the treatment plan in the “medical decision making” (MDM) section.

Example: Even though the 59-year-old with HTN and sore throat is being seen for an illness/injury that is not related to the chronic illness which is not at-goal, with proper documentation, this can be coded for a level 4 visit.

3. Failure to Document Independent Historian

Obtaining history from multiple historians is additional work and increases the complexity of medical care, yet providers frequently fail to document this. An independent historian can be a parent, guardian, surrogate, spouse, or witness, to name a few, who provides all or part of the history because the patient is unable to provide a complete or reliable history due to verbal difficulties, dementia, psychosis, or because a confirmatory history is judged to be necessary. The independent history does not need to be obtained directly in person. Phone calls count. Interpreter services, importantly, do not count towards use of independent historians. Most significantly, independent historians need to be identified as such in our documentation.

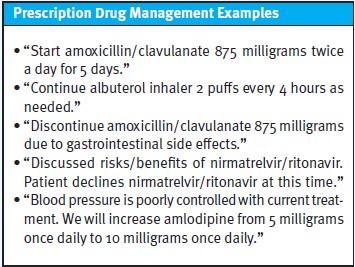

4. Failure to Document Prescription Drug Management

In UC, we are constantly prescribing and adjusting medications, but we infrequently document all these discussions to capture this work for our coding. Prescription drug management criteria are met when a provider discusses, starts, continues, discontinues, or adjusts a prescription medication. Documentation of the drug, strength, and dosage should be noted.

Prescription Drug Management Examples

- “Start amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 milligrams twice a day for 5 days.”

- “Continue albuterol inhaler 2 puffs every 4 hours as needed.”

- “Discontinue amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 milligrams due to gastrointestinal side effects.”

- “Discussed risks/benefits of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Patient declines nirmatrelvir/ritonavir at this time.”

- “Blood pressure is poorly controlled with current treatment. We will increase amlodipine from 5 milligrams once daily to 10 milligrams once daily.”

5. Failure to Discuss Tests That Are Considered But Not Ordered

We commonly consider many tests which are not ordered, either because we ultimately deem them to be not indicated or because the patient declines for some reason. If you recommend point-of-care tests or other labs, but the patient declines, document this conversation to receive credit. Similarly, if you consider further testing such as a chest x-ray for a patient with a cough, but decide that it’s not necessary because the patient has normal vital signs and significant rhinorrhea, document this as well. Documenting these will count toward the risk/complexity of patient management. If a patient declines a test that you’ve recommended, it’s important to document both the conversation and the rationale given for the patient to decline the test.

6. Failure to Mention Comorbidities

If the patient has a comorbid condition that could increase the risk of complications and/or management of the patient, these conditions should be added as a diagnosis, and a brief treatment plan should be included in the MDM. For example, in a diabetic patient who presents with a foot wound, the diabetes would significantly increase the risk for infection and poor healing. Adding diabetes as a secondary diagnosis and a brief treatment plan such as, “patient will continue metformin 500 milligrams twice a day, check blood glucose level daily, maintain a strict diabetic diet, and follow up with their primary care provider,” is sufficient.

Consider when and why to use comorbid conditions. The American Medical Association (AMA) guidelines1 state “comorbidities and underlying diseases, in and of themselves, are not considered in selecting a level of evaluation and management services unless they are addressed, and their presence increases the amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed or the risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.”

Examples would include:

- The diabetic patient presenting with any wound with counseling on diabetes

- A COVID-positive individual exhibiting multiple chronic conditions

- A patient with HTN experiencing chest pain and shortness of breath

- A daily tobacco user presenting with a cough with counseling on smoking cessation

Examples would not include:

- Notation in the patient’s medical record that another professional is managing the problem without additional assessment or care coordination documented

- Referral without evaluation (by history, examination, or diagnostic studies) or consideration of treatment

It is not enough to just note the patient has a comorbid condition. It must be, “addressed and their presence increases the amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed or the risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.”1 A problem is addressed or managed when it is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the provider. For example, “Blood pressure is 138/88 today. Patient will continue taking hydrochlorothiazide 25 milligrams once daily, log blood pressures daily, and follow up with his primary care provider for evaluation.” Adding the comorbid condition as a diagnosis is also warranted.

7. Failure to Document the Presence of Systemic Symptoms

Many patients present to UC with illnesses that produce expected and mild systemic symptoms, thus it’s understandable that these symptoms, such as anorexia with the flu, might not be commented upon in our charts. Yet from a coding perspective, this matters. Systemic symptoms would include fevers, nausea and vomiting not in the setting of gastroenteritis, moderate-severe fatigue, confusion, dizziness, rash which is not dermatologic in nature, body aches, and loss of appetite, to name a few. To meet the criteria for “acute illness with systemic symptoms,” the AMA guidelines state, “systemic symptoms may not be general but may be single system.”1 Most influenza, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, and COVID-19 patients would meet this criterion.

8. Failure to Discuss the Decision to Refer Patients to an Emergency Department

Most patients who we feel would benefit from immediate emergency department (ED) referral or transfer via emergency medical services will meet criteria for a level 5 visit given the presumption you are considering high-risk conditions. Documentation of the patient’s condition and diagnoses you are concerned about as well as any abnormal vital signs will help support a level 5 code. For the patient who is stable with normal vital signs, documentation of a differential diagnosis would be helpful when choosing the correct level of service. For example, the chest pain patient with a normal electrocardiogram and normal vital signs, who also seems more unwell than these objective measures would indicate warrants documenting a differential diagnosis to include possible the possibility of acute coronary syndrome or pulmonary embolism to ensure that the level 5 code is deemed justifiable for the visit.

9. Failure to Chart an Undiagnosed New Problem with Uncertain Prognosis

By virtue of the nature of urgent care, we see many patients with new, undifferentiated problems. A patient presenting with symptoms such as persistent fatigue, unexplained weight loss, and enlarged lymph nodes would fit into this category. Another example might be a patient with a sense of nausea, dizziness, or abdominal bloating. Despite a reasonable history, physical exam and possibly a screening point-of-care lab test or two, the exact cause of these symptoms remains unknown, as is often the case. There remains significant uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis and prognosis for such patients. Most of us will have conversations about this diagnostic uncertainty and need for ongoing monitoring of symptoms and follow-up, but less commonly do we document this. Additional patients that commonly fit into this category are those with low-risk chest pain, abdominal pain, or headache when they do not require immediate ED referral.

Conclusion

Our documentation is the only tool we have to capture the complex cognitive work we perform in evaluation and management of patients in UC centers. The “level” of our coding—designated by a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code—delineates how much we are reimbursed for the care we provide.3

Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services view “undercoding” as similarly fraudulent to “overcoding,”4 so we have an ethical responsibility to document a code that reflects the care that we provide. By recognizing the common coding pitfalls discussed above, UC clinicians can better ensure their documentation is sufficiently accurate and comprehensive to support an appropriate code.

References

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf Accessed February 7, 2024.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coordination-benefits-recovery/overview/icd-code-lists. Accessed February 12, 2024.

- American Medical Association. CPT Codes. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/cpt-codes. Accessed February 12, 2024.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Medicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/MLN-Publications-Items/MLN4649244?DLPage=1&DLEntries=10&DLFilter=frau&DLSort=0&DLSortDir=descending Accessed February 12, 2024.

Read More

- Identifying (And Resolving) Common Billing Pitfalls

- Decreasing Denials And Rejections Through Your Urgent Care Operating Model

- Charting With Purpose: Precision Strategies For Accurate Coding And Malpractice Defense

Download the article PDF Here