Urgent message: As it is common for human trafficking victims to present to urgent care, providers should be able to understand and identify common red flags in the patient presentation, history, and physical exam; treat immediate medical concerns; and know how to refer and safely provide resources for suspected cases.

Preeti Panda, MD

Citation: Panda P. Human trafficking in the urgent care setting: recognizing and referring vulnerable patients. J Urgent Care Med. 2023;17(6):13-22.

Key words: Human trafficking, child trafficking, exploitation, public health

CASE PRESENTATION

A 15-year-old male presents to the urgent care clinic for evaluation of a fall. He states he fell off his bike earlier today onto his right arm. He is unaccompanied on today’s visit. When questioned about his parents and living situation, he states he lives with his mother but fights with her frequently, and is currently staying with a friend. His vitals are normal for his age. On examination you note tenderness to the distal radius. The extremity is neurovascularly intact and no other signs of injury are noted. Away from the room, the nurse notifies you they were able to obtain consent to treat from the patient’s mother over the phone, and notes his mother seemed concerned that he had not been home for several days. X-rays of the right upper extremity reveal a nondisplaced buckle fracture of the distal radius. After a splint is placed, you talk to the patient about his discharge disposition. On further questioning, he reveals his friend is an older man who is known to his family, and that he would like to return to the man’s home upon discharge. He also requests no paperwork be given to him documenting his urgent care visit today. When discussing outpatient medical follow-up for his injury, he states that it will be difficult for him to make the appointment and asks if it is absolutely necessary. After leaving the room, you feel uneasy about your patient’s social situation, and suspect there is more to the story. At this time, it feels unsafe to discharge your patient to his friend, but the next steps are unclear.

INTRODUCTION

Human trafficking is a pervasive public health issue affecting children and adults in communities across the United States. Human trafficking is legally defined as the recruitment of individuals for labor or commercial sex acts through use of force, fraud or coercion, for purposes of involuntary servitude.1,2 More simply put, it is the unjust exploitation of individuals for a profit by a trafficker.

For a case to qualify as human trafficking, all three elements of acts, means, and purpose must be present.

Acts refers to a trafficker’s recruitment of the person into trafficking; means refers to the manipulation and exploitation of the individual through force, fraud or coercion; and purpose refers to the sex or labor service the person is forced to provide.3 Children below the age of 18 engaged in commercial sex acts are by default acknowledged as trafficked persons, with no need to prove force, fraud, or coercion.

The International Labour Organization estimates 50 million individuals are trafficked globally, about a quarter of whom are children.4 Roughly 7 million individuals are trafficked in high-income countries such as the U.S.4 Domestically, this issue is present in all 50 states, and in big and small cities.5,6

In 2020, the National Human Trafficking Hotline identified almost 17,000 cases of human trafficking in the U.S. across various sex and labor industries.7 Prevalence estimates in the United States are limited due to the hidden nature of this crime, and true prevalence of human trafficking in the U.S. is likely much higher than the reported cases.

Trafficked individuals can experience a range of medical problems and have unique medical needs. They may experience acute conditions or exacerbations of chronic health issues as a direct result of their trafficking situation, and often suffer from long-lasting effects of physical and psychological trauma experienced during trafficking into survivorhood.8–10 Trafficked individuals frequently seek healthcare, both while trafficked and as survivors.11,12 It is, therefore, well established that healthcare providers play an important role in recognizing and intervening for trafficked individuals.

Trafficking and Urgent Care

This is especially relevant to urgent care providers. Studies have demonstrated that almost 90% of trafficked individuals have accessed health services during trafficking, with reported ranges of 22%-29% of victims presenting to urgent care settings.12,13 An additional 60%-95% of survivors have utilized emergency department services, which are often inclusive of fast-track and urgent care areas, and certain studies combine ED and urgent care data.12–14

Unfortunately, trafficked individuals are commonly missed by medical providers, with one study demonstrating 90% of trafficked individuals had presented to various healthcare settings prior to being identified.8 Medical professionals also have low rates of reporting human trafficking—only making up about 3% of over 50,000 calls made to the National Human Trafficking Hotline (NHTH) in 2020—further highlighting the need for improved education and awareness.6

To best serve patients who may have been trafficked, urgent care practitioners should understand common ways trafficked individuals may present to urgent care settings and be prepared to refer potential victims to appropriate services.

This review article provides a framework for urgent care providers to be able to: 1) understand and identify common red flags in the patient presentation, history, and physical exam; 2) treat immediate medical concerns; 3) know how to refer and safely provide resources for suspected cases.

OVERVIEW OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Patient Characteristics

The ability to recognize trafficking in the medical setting starts with understanding characteristics of trafficked individuals, patient risk-factors, and the nature of exploitive situations. Statistics on demographic characteristics of trafficked individuals are limited and likely an under-characterization of the full scope. However, the existing data can be used as a general proxy of sociodemographics.

While the average reported age of globally identified victims is 27, human trafficking affects individuals of all ages—inclusive of children below 8-years-old to adults over 50-years-old. Peak ages of entry into trafficking among children are mid-to-late teens.15

Human trafficking affects individuals across genders as well. In 2020, the NHTH reported that 85% of sex trafficking victims were female, 8% were male, and 1% were gender minorities (ie, individuals who do not identify as cisgender male or female). Of individuals who experienced labor trafficking, 58% were females 43% were male, and 0.1% were gender minorities. This parallels pooled global estimates, which show 70% of identified victims are female, 25% are male, and 5% are gender minorities.16

Male and gender-minority victims likely represent a higher portion of the trafficked population than the data indicate; however, they have historically not been well-identified due to lack of awareness, focus on female victims, and stigma preventing disclosure.17

While trafficked individuals are often thought of as international victims brought into the United States, U.S. citizens comprised 40% of all trafficking cases and 60% of sex trafficking cases reported to the NHTH.6

Of note, per definitions of human trafficking, individuals do not need to cross state or international lines to be considered trafficked—the designation of trafficking is centered on the presence of exploitation.3

Though race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status of trafficked individuals in the U.S. have not been systematically studied on a large scale, existing data demonstrate that trafficking affects individuals across races and ethnicities, and can affect individuals above and below the poverty line.13,14,18 Organizations providing direct services to trafficked individuals have reported that human trafficking disproportionately affects minority populations and those living in poverty.19,20

Risk Factors

While it is possible that an individual from any background can be trafficked, patients at greatest risk include those who have experienced prior trauma, including physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, intimate partner violence, and other sexual violence.

Adults and children experiencing housing instability, homelessness, and financial instability are at higher risk of human trafficking.7

Children with these vulnerabilities have often spent time in group homes or homeless shelters, or frequently run away from home. Furthermore, children who have been involved with county services, including child protective services and the juvenile justice system, are at higher risk of trafficking.21

The LGBTQ population is at an increased risk for experiencing trauma, abuse, and employment discrimination, among other contributing factors, which increases their risks of being exploited.22

Refugees, immigrants, and undocumented individuals are vulnerable due to instability regarding their economic and legal status, as well as from prior history of trauma.

Substance abuse and dependence is a risk factor due to increased likelihood of housing and financial distress, as well as ease of means of control for traffickers.

Finally, individuals with mental health problems, disabilities, and special needs are also a vulnerable population at increased risk of exploitation.23

Traffickers and Means of Control

Understanding the nature of perpetrators and coercive relationships is important in learning to screen for human trafficking in the clinical setting. Traffickers can be of any age, gender, racial, or ethnic background. They could be employers, friends, intimate partners, family members, and groups or coalitions, including gangs.

While the existence of familial trafficking may be surprising, this is unfortunately common. Trafficking by a family member is the most commonly identified victim-recruiter relationship involving child victims, with 31% of cases reported to the NHTH involved trafficking by family members.7,24

Traffickers employ methods of control to both recruit victims and prevent them from leaving. The most common are psychological abuse, threats, false promises, physical abuse, and inhibition of financial independence. Physical and sexual violence, restriction of medical care, use of illicit substances, and withholding of personal necessities are common methods of control that may contribute to health problems of trafficked individuals.24 While traffickers may restrict movement, this is usually not through physical bondage, but instead through threats, psychological abuse, and other aforementioned means of control.

Types of Trafficking

Twenty-five distinct industries affected by human trafficking in the U.S. have been categorized. Examples of industries affected by sex trafficking include escort services, massage businesses, strip clubs, and pornography. Industries affected by labor trafficking are more broad, and include domestic work, construction, traveling sales crews, agriculture and food services, and others.25 Globally, domestic work, agriculture, and construction are among the industries most reported to involve labor trafficking.24

To facilitate a more tangible understanding of characteristics of human trafficking victims, traffickers, and means of control, see Tables 1A and 1B.

Table 1A. Example Scenarios of Human Sex Trafficking

| Scenario | Methods of Control |

| A woman is groomed by her boyfriend for a period of time with love, gifts, and support. He then asks her to engage in sexual acts with his “friends” to help him earn money because he is in a tough place financially. It is initially framed as temporary but continues more often, and the nature of their relationship gradually changes as he becomes more controlling and abusive. | Financial: The boyfriend (trafficker) keeps all the money she earns, only giving her a small allowance. Psychological: The trafficker threatens to stop loving her if she stops helping him, and to tell her friends what she has been doing. He doubts her love and commitment to him whenever she asks to stop. Abuse: The trafficker beats her if she does not comply, and states it is her fault for making him more stressed about his financial situation. |

| A child’s mother has a personal history of abuse and sexual violence, and struggles with drug addiction and financial instability. Her drug dealer requests to engage in sexual acts with her 8-year-old son in exchange for drugs, to which she complies.* | Psychological: The mother (trafficker) normalizes these activities from her own experiences, and tells the child it is important to keep this secret so they stay safe. The child loves their mother, and as a minor has no other financial or emotional support system. |

| A young woman from the Philippines is promised work abroad to help support her family. The recruiter brings her to the U.S. and withholds her passport. They require her to work in an illicit massage business. | Legal: The business owner (trafficker) withholds legal documents and threatens deportation or jail time. Financial: The trafficker forces her to work until she pays off a “debt”; food and shelter are provided but no additional money is given. Abuse: The trafficker employs psychological and physical abuse, withholds basic necessities and limits medical care. |

| A 14-year-old transgender male runs away from home to escape physical abuse. He meets other homeless youth who introduce him to an older couple who will give him food and shelter in exchange for sexual favors for them and their “friends.”* | Financial: The child has no financial support system, or other means of obtaining shelter and food. Abuse: The older couple (traffickers) employ psychological abuse by capitalizing on his lack of existing family support and need for love and emotional support. |

*Presence of force, fraud or coercion are not required when a child is trading sexual acts for anything of value

Table 1B. Example Scenarios of Human Labor Trafficking

| Scenario | Methods of Control |

| A man from Guatemala is recruited for a legal farming job in the U.S. and promised a temporary visa. On arrival, the recruiter states he has to pay off the debt for his visa costs, and is also charged for shelter, food, and transportation provided by the recruiter, adding to his debt. All of his salary goes towards paying off this debt, and he is required to work long hours without days off. | Financial: The job recruiter (trafficker) fraudulently increases the amount of debt owed and takes 100% of wages, barring him from achieving any financial independence. Legal: The trafficker withholds temporary visa and legal documents from the worker, and threatens jail time for entering illegally.Abuse: The trafficker employs methods of psychological abuse, including threatening his family abroad and blacklisting him from local work in the area. |

| A homeless 15-year-old girl who ran away from home due to abuse is approached by an adult who offers her a job selling items door-to-door. She agrees and is required to sell a minimum quota each day, but is never given wages. | Financial: The job recruiter (trafficker) withholds wages and states they are using all the money for the child’s food and shelter. Abuse: The trafficker employs threats of violence and keeps the child isolated. The child lacks an emotional support system and does not feel they have anywhere else to turn. |

| A Native-American male teenager is recruited by a local casino owner to sell illicit substances and sexual favors to customers. The boy is provided basic necessities, cash, and designer items for his services. The boy’s family is struggling financially.* | Financial: The trafficker provides financial incentives that the boy in turn provides to his family. Abuse: The trafficker capitalizes on the shame the child feels for engaging in these acts, and threatens to tell the community what he is doing if he leaves. |

*Presence of force, fraud or coercion are not required when a child is trading sexual acts for anything of value

UNIQUE HEALTHCARE NEEDS OF TRAFFICKED INDIVIDUALS

Trafficked individuals have unique healthcare needs and may present to healthcare settings for a variety of conditions.12 They may experience acute conditions as a direct result of their trafficking situation or may have existing chronic conditions exacerbated by trafficking. Survivors also experience long-term health sequalae years after leaving exploitation.

While traumatic injuries, sexual health problems, and mental health issues are intuitive health consequences of human trafficking, health issues of trafficked individuals can span multiple systems.10,26–28 Potential presenting health complaints, and their respective underlying risk factors from situations of human trafficking, are highlighted in Table 2. They include many conditions commonly treated in the urgent care setting. Urgent care providers may also see higher-acuity complaints that require referral to a higher level of care. Trafficked individuals may have limited access to healthcare, with constraints on which health facilities are nearby or have accessible hours, making urgent cares a potentially convenient option.11

Table 2. Common Health Ailments of Trafficked Individuals10,12,26–28

| Health Domain or System Involved | Possible Health Problems | Trafficking-Specific Risk Factors |

| Constitutional | Fatigue Dizziness Weight Loss | Inadequate living conditions Depravation of basic necessities Sleep depravation Inadequate nutrition |

| Sexual, reproductive, and genitourinary | Pregnancy complications (preterm labor, pregnancy loss) Unwanted pregnancy (forced abortion, unsafe abortion) Pelvic and vaginal pain Pelvic inflammatory disorder Dyspareunia Dysuria Vaginal discharge Vaginal bleeding Traumatic GU injuries Foreign bodies | Sexual assault and violence Physical violence experienced during pregnancy Lack of choice or control regarding safe sex practices |

| Infectious disease | Sexually transmitted infections Urinary tract infections Hepatitis HIV/AIDS Skin infections (cellulitis, abscess) | Sexual assault and violence Inadequate working conditions Lack of choice or control regarding safe sex practices Poor hygiene Depravation of basic necessities Substance use as means of control or escape |

| Trauma musculoskeletal | Blunt traumatic injuries, including contusions, sprains, fractures, bruising and abrasions (acute and chronic) Penetrating traumatic injuries, including stab wounds, puncture wounds, gunshot wounds, and lacerations Strangulation Burns, including cigarette burns and branding Traumatic brain injury (mild and severe) Back pain (acute and chronic) Joint pain (acute and chronic) Myalgias (acute and chronic) | Physical violence and abuse from traffickers or solicitors of their services Torture Physical restraining, bondage, or confinement Dangerous working conditions Repetitive physical tasks |

| Neurologic | Headaches Memory problems Cognitive problems Conversion disorder Seizures Nonepileptic seizures | Physical violenceLong-term blunt force trauma and repeated head injury Dangerous working conditions Psychological and emotional abuse |

| Gastrointestinal and Nutrition | Malnutrition Abdominal pain (acute and chronic) Irritable bowel syndrome | Inadequate nutrition Physical violence Psychological and emotional abuse |

| Cardiorespiratory | Difficulty breathing Palpitations Chest pain | Physical violence Psychological and emotional abuse |

| Dermatologic | Rashes Sores, ulcers Burns, branding, and tattoos Scars Scabies, bedbugs | Poor hygiene Inadequate living conditions Withholding of medical care Physical violence Methods of control by traffickers |

| Psychological | Anxiety Depression Post-traumatic stress disorder Suicidal ideation Attempted suicide Somatic symptom disorder Substance use | Psychological and emotional abuse Physical and sexual trauma Isolation Substance use as means of control or escape Other methods of control, including fraud and deception Inadequate living conditions Depravation of basic necessities |

| Environmental | Poisoning from various toxic substances, eg, tobacco poisoning, pesticide poisoning Sunburn or poisoning Heat stroke Frostbite | Dangerous working conditions Lack of appropriate protective equipment Inadequate living conditions Depravation of basic necessities |

| Other | Exacerbation of pre-existing chronic illnesses or progression of pre-existing disabilities; eg, poorly controlled asthma or COPD with frequent exacerbations, poorly controlled type I diabetes with frequent presentation for DKA | Withholding of medical care Inadequate living conditions Depravation of basic necessities |

APPROACH TO POTENTIALLY TRAFFICKED PATIENTS IN THE URGENT CARE SETTING

The approach to comprehensive evaluation of a potentially trafficked patient in the urgent care setting includes treatment of urgent medical concerns, screening, and safe referral.

Treat Immediate Medical Concerns

The first priority is to address any immediate medical concerns. Necessary medical care should not be delayed, and screening for human trafficking if red flags are present should be incorporated after the plan for treating urgent medical complaints is in place.

In urgent care settings, acute medical problems may need escalation of care and referral to an emergency department. Patients may also require forensic exam for assault, which is time-sensitive and varies by institution. In these cases, emergent care should not be delayed. Direct verbal handoff of concerns for trafficking should be performed confidentially to the accepting provider, and mandated reporting should be performed by the urgent care provider if indicated.

Screening for Signs of Human Trafficking

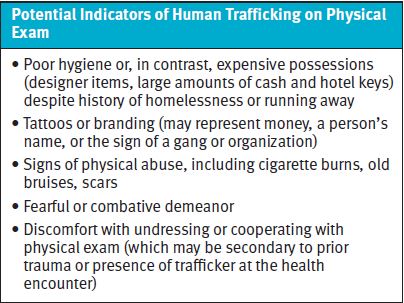

A patient may exhibit signs, or red flags, of human trafficking during the history and physical exam (Table 3). These potential indicators should be considered in conjunction with the aforementioned historical risk factors and patient characteristics that are commonly seen in trafficked populations.

Potential indicators of human trafficking

Red flags for human trafficking during the history include late presentation to care, history inconsistent with pattern of injury, and concern for unsafe working conditions. Patients who have experienced trafficking may have frequent utilization of urgent care and emergency department services, lack of primary care, and repeated exacerbations of chronic disease with poor medication compliance, as a result of withholding of basic necessities and medical care.29

Individuals experiencing exploitation may be accompanied by their trafficker. This person may be introduced as a family member, friend, significant other, or their relationship may be ambiguous. In cases of child trafficking, a much older companion who is either a significant other or nonguardian can be a red flag.30

It is important to keep in mind that traffickers span all ages and demographics, and that traffickers may be family members of the patient. A patient who is fearful of their companion, or a companion who exerts significant dominance and control during the patient encounter should raise an index of suspicion for an exploitive or abusive situation. Further, as noted, traffickers may be unwilling to let the patient go to other areas such as radiology, or to the bathroom, without them.27

Red flags on physical exam include a general fearful or combative demeanor of the patient, including refusal to undress or cooperate with standard aspects of the physical exam. These actions may be due to the patient’s prior trauma, previous traumatic experiences with the healthcare system, or fear of abuse being identified by the provider with or without the trafficker present.

Physical exam may reveal poor hygiene, or conversely a patient may be very well groomed with expensive possessions despite a social history of homelessness or running away.

If signs of physical abuse are present, providers should consider the larger picture to evaluate if other signs of exploitation are present. Traffickers may engage in “branding” a victim with a tattoo or burn, which may represent the trafficker’s name, gang or organization name, sexually explicit language, or representations of money to signify the individual as their property.31

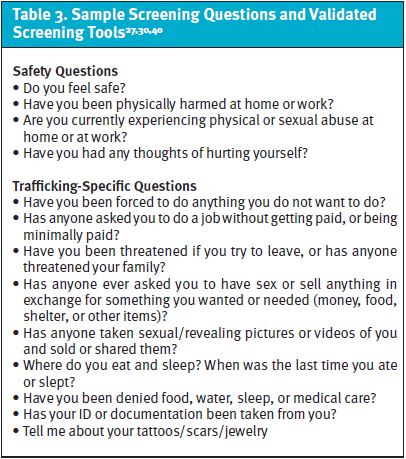

When present, red flags for human trafficking should prompt providers to ask additional screening questions to determine if the patient is at risk of being exploited. Table 3 offers sample screening questions.

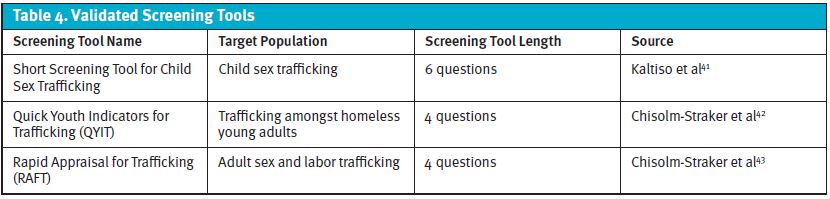

Several human trafficking screening tools have been validated for specific subpopulations of human trafficking, and may be used at the bedside to aid in screening for individuals at risk of human trafficking. Depending on your patient population, these screening tools may be useful for your practice setting or specific patient scenario and can be referenced accordingly. (See Table 4.)

Overall, providers should take steps to ask additional clarifying questions to determine the patient’s overall risk of exploitation and assist with informing next steps.

Best practices for trauma-informed interviewing

Trafficked individuals have experienced complex trauma and have complex relationships with those who are exploiting them; this is referred to as trauma bonding. Trauma-informed interviewing techniques should be considered to establish a safe space and build rapport.

During screening, efforts should be made to interview the patient alone. If needed, providers should collaborate with their team to identify creative ways to separate a patient from their companion if they are unwilling to step out of the room. For example, a nurse or medical assistant can help facilitate escorting the patient to a private area on the way to leave a urine sample or obtain an x-ray. Providers should use their own judgement in situations where the accompanying individual is combative in leaving the patient alone, and balance separating the patient with considerations of their safety following the visit. A certified medical interpreter should be used when indicated.

Limits of confidentiality based on state-specific mandated reporting laws should be clearly communicated to the patient prior to safety assessments. Providers should ask screening questions in a nonjudgmental manner and take time to listen to patient’s concerns. Regardless of risk, the patient’s wishes should be respected outside the limits of mandated reporting. Overall, the healthcare team should make efforts not to retraumatize trafficked and at-risk patients during the health encounter.32,33

A definite disclosure of human trafficking should not be the goal of patient screening. The provider’s responsibility is to create a safe space for the patient, determine risk of human trafficking, and provide appropriate resources. The factors leading to disclosure are complex, and often have significant implications for patient safety. Disclosure of exploitation is therefore less common than encountering patients with risks and red flags. Victims of human trafficking and those with red flags both benefit from connection to resources.33,34

Safe Referral

After urgent medical issues have been addressed, the next step is to facilitate safe referral and/or provide resources. These steps should be taken for any individual for whom there is a clinical suspicion of human trafficking, regardless of disclosure or confirmation.

The approach to referral and resource provision for suspected human trafficking varies by location and institution. The following are common resources or protocols providers can look to for guidance:

- Health System Protocol Your health system or organization may already have a protocol or clinical pathway in place detailing what to do in cases of suspected human trafficking. This guidance may be co-located with protocols on other forms of violence, including child abuse and intimate partner violence. If protocol information is unavailable, consulting with locally available specialists (eg, child abuse physician, social worker, or sexual assault nurse examiners affiliated with an emergency department) may be useful for providing guidance.

- Community Agencies Your health network may have a relationship with a local human trafficking task force, child protection agency, or law enforcement group responsible for handling cases of suspected trafficking. These groups may be helpful in providing guidance on next steps and patient resources.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline (NHTH) Regardless of whether an institutional protocol exists or not, any person, including providers, can call the NHTH. This nationally available service operates via phone, text, or chat, and allows any person to report a suspected case. Agents will walk clinicians through next steps and can provide information on local law enforcement, nongovernmental agencies, safe transportation, and patient resources. Providers can call by themselves, or with the patient present if they give consent. Providers are encouraged to call for further guidance where next steps are unclear. The NHTH website includes a referral directory where providers can search by zip code for local agencies providing services that may be of benefit to the patient.

- State-Mandated Reporting Laws Providers should be familiar with state-mandated reporting laws concerning human trafficking, child abuse, suicidal ideation, and other threats to patient well-being. Some states require suspected cases of child trafficking to be reported to child protection agencies. Clinicians should follow their state protocols when applicable, and be clear with patients regarding limits to confidentiality.

In cases of confirmed trafficking, clinicians should discuss possible next steps collaboratively with the patient. Providers should inform patients of options to contact their local agency or national hotline regarding options for safe transportation, housing, and legal services. Providers can make the call alone or with the patient present. The patient’s wishes and preferences should be respected. Exceptions to confidentiality include harm to self/suicidal ideation, children experiencing human trafficking in states with mandated reporting, and when ongoing child abuse is identified. All of these require reporting to the appropriate institutional official or county agency.

When patients with confirmed trafficking decline reporting, or in cases of suspected human trafficking without definite disclosure, clinicians should take steps to provide resources to patients.

Primarily, the provider should emphasize that the urgent care is a safe space that they may return to in the future should they need help. Other local health systems, including emergency departments, may also be highlighted as places the patient can utilize. Based on the nature of the encounter and answers to screening patients, the provider should attempt to identify additional resources that may benefit the patient.

From a medical standpoint, patients should be given referrals or information on connecting with mental health and primary care services. Other resources to pass along to patients include local agencies, safe housing, food banks, and legal services. These resources may be found by consulting a health system protocol, expert consultant, or social worker, or through the NHTH referral directory.

The NHTH can also be contacted by providers for purposes of identifying and responsibly providing resources while keeping the patient’s identity confidential. Importantly, providers can educate patients on how to contact the NHTH in the future.

Clinicians should practice shared decision-making with the patient regarding how contact information for services can be provided. Providers should be aware that printed materials and information on the patients mobile device may be accessible to their trafficker, which could put the patient at increased risk.

Responding to cases of potential human trafficking in the UC setting can be challenging. Providers are likely to encounter situations where next steps are unclear. In these cases, providers should prioritize the safety of the patient first, and consult local resources or the national hotline for recommendations.

The urgent care setting can also pose unique challenges regarding patient disposition. UC centers often have limited access to resources such as social workers or forensic examiners, and suspected cases may require transfer to a higher level of care. Urgent care settings may also have limited capacity to board patients.

As consulting with community agencies or the NHTH and determining patient disposition may take time, providers should collaborate with their nursing staff to identify a safe space for patient boarding once medical concerns have been addressed.

Documentation

Chart documentation should be focused on objective and medically relevant details of the patient encounter. Providers should avoid phrases that can introduce doubt into the situation—for example, phrases such as “allegedly”—and use objective language in their history and assessment.

Any physical exam findings indicative of abuse or branding should be clearly documented.27 In cases where there is no definite disclosure of human trafficking but red flags are present, urgent care providers are encouraged to document the red flags and their suspicion of exploitation. As trafficked individuals can present to care multiple times before leaving their situation, the patient may present to the urgent care site in the future. This documentation can be very useful in alerting providers seeing the patient in the future to create a safe space for the patient, continue to watch for red flags, ask appropriate screening questions, and provide resources.

It is important that concerns of human trafficking are documented in a protected area of the chart. Many health systems now have patient portals, which can allow patients and families to view provider notes. Urgent care clinicians should consult with their leadership teams to identify how to create confidential notes which may be used to document sensitive situations, including suspected human trafficking.

Human trafficking-related ICD-10 codes were instituted in 2018, and may be used to document suspected or confirmed trafficking.35 Utilization of these codes have the potential to improve trauma-informed care for the patient’s future visits by alerting future providers to the history, and to benefit research-and-response efforts in the healthcare setting.36 However, clinicians should take steps to enter patient coding confidentially, and be careful in utilizing these codes if they cannot be hidden in the electronic medical record and could be printed on patient materials or viewed in online patient portals.37

CASE FOLLOW-UP

The patient’s buckle fracture seems consistent with the mechanism of injury you obtained from the history. A fall off a bike may truly be the reason he sustained the injury, but other red flags during the encounter (unstable home situation, running away, older adult “friend,” wary about paperwork, and not wanting medical follow-up) prompted further investigation into whether he was being exploited.

You have established rapport with the patient, and state that you would like to ask additional questions regarding his social situation. You disclose that you can keep the conversation confidential unless someone is harming him, exploiting him, or if he has thoughts of harming himself. With his permission, you begin to ask him screening questions.

At first he states he feels safe at home with his mother and his friend. When asked if anyone has made him do something he does not want to do, or if he has exchanged sex for anything of value, he is initially quiet.

On further questioning, he tells you his friend sometimes asks him for sexual favors in exchange for food and a place to sleep. He starts to share more but then states he is not ready to talk about it. He says he does want help and agrees to talk to the human trafficking hotline. You notify your nurse that you are boarding the patient for 1-2 hours while you figure out disposition.

After calling the hotline with the patient present, the agent facilitates connection to the local human trafficking task force and child protective services agency for mandated reporting. Safe transport is arranged for the patient to the local pediatric emergency room, where the task force and protective services will perform a comprehensive assessment and determine safe patient placement. Prior to transport, you provide a confidential verbal handoff to the receiving physician at the pediatric emergency department.

CONCLUSION

Recognizing human trafficking in healthcare settings can be challenging and requires an index of suspicion. It is important for urgent care providers to understand the nature of human trafficking and presenting signs. Recognizing red flags for human trafficking, creating a safe space for patients, and providing resources can make a significant impact on trafficked individuals, regardless of their definite disclosure of exploitation.

To best serve patients experiencing human trafficking, urgent care providers and staff should take steps to familiarize themselves with local resources and policies for confidential electronic medical record documentation.

REFERENCES

- The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA).; 2000. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/humantrafficking/key-legislation. Accessed October 19, 2022.

- Frederick Douglass Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Reauthorization Act of 2018.; 2018. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/humantrafficking/key-legislation. Accessed October 19, 2022.

- Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report. U.S. Department of State; 2022. Available at: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/. Accessed October 14, 2022.

- International Labour Organization. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage. International Labour Organization, Walk Free Foundation, International Organization for Migration; 2022. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/WCMS_854733/lang–en/index.htm. Accessed October 14, 2022.

- Tillyer MS, Smith MR, Tillyer R. Findings from the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline. J Hum Traffick. Published online June 14, 2021:1-10.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. National Human Trafficking Hotline Data Report.; 2021. Available at: https://humantraffickinghotline.org/resources/2020-national-hotline-annual-report. Accessed October 19, 2022.

- Polaris Project. Human Trafficking Trends in 2020; 2022. Available at: https://polarisproject.org/2020-us-national-human-trafficking-hotline-statistics/. Accessed October 19, 2022.

- Ertl S, Bokor B, Tuchman L, et al. Healthcare needs and utilization patterns of sex-trafficked youth: missed opportunities at a children’s hospital. Child Care Health Dev. 2020;46(4):422-428.

- Dank M, Farrell A, Zhang S, et al. An Exploratory Study of Labor Trafficking Among U.S. Citizen Victims. John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Northeastern University, Umass Lowell; 2021.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The physical and psychological health consequences of women and adolescents trafficked in Europe. Lond Sch Hyg Trop Med. Published online 2009.

- Panda P, Garg A, Lee S, Sehgal AR. Barriers to the access and utilization of healthcare for trafficked youth in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;121:105259.

- Lederer L, Wetzel CA. Annals of Health Law. Health Policy Law Rev Loyola Univ Chic Sch Law. 2014;23(1).

- Richie-Zavaleta AC, Villanueva A, Martinez-Donate A, et al. Sex trafficking victims at their junction with the healthcare setting — a mixed-methods inquiry. J Hum Traffick. Published online 2019.

- Hornor G, Sherfield J. Commercial sexual exploitation of children: health care use and case characteristics. J Pediatr Health Care. Published online 2018.

- Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC). Age of Victims: Children and Adults. Published October 2022. https://www.ctdatacollaborative.org/story/age-victims-children-and-adults. Accessed October 20, 2022.

- Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC). Human trafficking and gender: differences, similarities and trends. Published October 2022. Available at: https://www.ctdatacollaborative.org/story/human-trafficking-and-gender-differences-similarities-and-trends. Accessed October 20, 2022.

- Barron IM, Frost C. Men, boys, and LGBTQ: invisible victims of human trafficking. In: Walker L, Gaviria G, Gopal K, eds. Handbook of Sex Trafficking: Feminist Transnational Perspectives. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018:73-84.

- Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, Greenbaum VJ. Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;44.

- Polaris Project. Racial Disparities, COVID-19, and Human Trafficking. Published 2020. Available at: https://polarisproject.org/blog/2020/07/racial-disparities-covid-19-and-human-trafficking/. Accessed December 14, 2021.

- Butler CN. The Racial Roots of Human Trafficking. UCLA Law Rev. 2015;(62). Available at: https://www.uclalawreview.org/racial-roots-human-trafficking/. Accessed December 16, 2021.

- Franchino-Olsen H. Vulnerabilities relevant for commercial sexual exploitation of children/domestic minor sex trafficking: a systematic review of risk factors. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021;22(1):99-111.

- Murphy LT, Covenant House International. Labor and Sex Trafficking Among Homeless Youth. Loyola Univ New Orleans Mod Slavery Res Proj. Published online 2016. https://covenanthousestudy.org/landing/trafficking/.

- Research to Policy Collaboration, Society for Community Research and Action. Preventing Human Trafficking Using Data-driven, Community-based Strategies. Published online 2018:4.

- Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC). Exploitation of Victims: Trends. Published 2022. Available at: https://www.ctdatacollaborative.org/story/exploitation-victims-trends. Accessed October 20, 2022.

- Polaris Project. The Typology of Modern Slavery.; 2017. https://polarisproject.org/typology-report

- Le PD, Ryan N, Rosenstock Y, Goldmann E. Health issues associated with commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of children in the United States: a systematic review. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):219-233.

- Shandro J, Chisolm-Straker M, Duber HC, et al. Human trafficking: a guide to identification and approach for the emergency physician. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(4):501-508.e1.

- Garg A, Panda P, Malay S, Slain KN. Human Trafficking ICD-10 code utilization in pediatric tertiary care centers within the United States. Front Pediatr. 2022;10. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fped.2022.818043. Accessed March 7, 2022.

- Alpert EJ, Ahn R, Albright E, et al. Human Trafficking: guidebook on identification, assessment, and response in the health care setting. MGH Hum Traffick Initiat Div Glob Health Hum Rights Dep Emerg Med Mass Gen Hosp. Published online 2014.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3).

- Fang S, Coverdale J, Nguyen P, Gordon M. Tattoo Recognition in screening for victims of human trafficking. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(10):824-827.

- Dignity Health, HEAL Trafficking, Pacific Survivor Center. PEARR Tool: Trauma-Informed Approach to Victim Assistance in Health Care Settings. Dignity Health Foundation; 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center, Department of Health and Human Services. Core competencies for human trafficking response in health care and behavioral health systems.2021.

- Panda P, Miller CL, Greenbaum VJ, Stoklosa HM. Newly released core competencies: an essential component to health systems’ human trafficking response. Delta 8.7. Published December 1, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://delta87.org/2021/12/newly-released-core-competencies-essential-component-health-systems-human-trafficking-response/

- American Hospital Association. ICD-10-CM Coding for Human Trafficking.; 2018. www.aha.org

- Greenbaum J, Stoklosa H. The healthcare response to human trafficking: a need for globally harmonized icd codes. PLoS Med. 2019;16(5):10-12.

- Greenbaum J, Garrett A, Chon K, et al. Principles for safe implementation of ICD codes for human trafficking. J Law Med Ethics. 2021;49(2):285-289.

- National Center on Child Trafficking. What Is Child Trafficking: Definitions and Examples. Georgia State University. Available at: https://ncct.gsu.edu/what-is-child-trafficking/. Accessed October 28, 2022.

- Polaris Project. Understanding Human Trafficking. Published 2019. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://polarisproject.org/understanding-human-trafficking/

- Garg A, Panda P, Malay S, Rose JA. A human trafficking educational program and point-of-care reference tool for pediatric residents. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11179.

- Kaltiso SAO, Greenbaum VJ, Agarwal M, et al. Evaluation of a screening tool for child sex trafficking among patients with high-risk chief complaints in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(11):1193-1203.

- Chisolm-Straker M, Sze J, Einbond J, et al. Screening for human trafficking among homeless young adults. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;98(September 2018):72-79.

- Chisolm-Straker M, Singer E, Strong D, et al. Validation of a screening tool for labor and sex trafficking among emergency department patients. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(5):e12558.

Manuscript submitted October 30, 2022; accepted November 1, 2022.

Author disclosures: Preeti Panda, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine. The author has no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

Read More

- Too Many Kids Are At Risk For Abuse And Trafficking. Ensure Your Urgent Care Center Is A Safe Haven

- Are Requests For Emergency Contraception A Red Flag For Domestic Abuse?

- Urgent Care Operators Can Help Reduce Elder Abuse—Here’s How