Published on

Urgent message: Unlike businesses that expect—and receive—full payment at the time services or goods are secured, urgent care centers often wait for full payment from third-party payors. Efficient management of accounts receivable is crucial to the center’s financial viability.

By Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc Practice Velocity

Urgent care centers—which appeal to consumers on the basis of high-visibility locations, extended hours, and walk-in convenience—are often compared to “retail” businesses. Unlike stores, restaurants, and other “retailers” who require full cash or credit card payment at time of service, however, most urgent care centers find it necessary to bill at least part of a visit’s cost to a third-party payor. The result is a mismatch between the center’s immediate expenditures for staff, rent, and supplies and the 30 to 90 days (or longer) it takes to receive insurance reimbursement.

Carrying accounts receivable is expensive, and an extended accounts receivable cycle can completely drain an otherwise viable center of its profitability. Not only are there direct costs of documenting, submitting, following up, and posting insurance claims – but when there is insufficient cash available to pay practice expenses, “working capital” must either be borrowed from the bank or retained from owners.

In any business, “cash is king.” To improve cash flow (and profitability) of an urgent care center, consider the following steps to reduce accounts receivable:

1. Financial policy. A common reason patients do not pay their medical bills is that they do not understand what they owe and why. Therefore, before a patient receives any treatment, the urgent care operator should clearly explain both the total expected cost of the visit and any copays, co-insurance, or deductibles that are required at time of service. The center’s financial policy should detail which insurance plans are accepted, how out-of-network insurance will be billed, the cost of a self-pay visit, and whether the patient will be billed his deductible or required to put down a “deposit.” The financial policy should be clearly communicated on the center’s website, verbally by the front office staff, and in written materials provided at registration. To assure patient understanding, many centers ask for a signed acknowledgement that patients have received, read, and will comply with the financial policy.

2. Insurance verification. Failure to verify insurance could result in a denied claim and a patient balance that never gets paid. Just because a patient presents an insurance card doesn’t mean he or she is insured. In a recessed economy, people transitioning between jobs often forego COBRA coverage, and some businesses reduce or drop employee benefits.In addition, plans are increasing patient out-of-pocket expense by way of copays, deductibles, and co-insurance. Even when an urgent care center is “in network” with a carrier’s primary PPO, the carrier’s HMO and affiliated plans may not offer an urgent care benefit or may require referral and pre-authorization. Therefore, prior to treatment, the front desk should contact the insurance carrier to confirm enrollment, coverage levels, and amounts to be collected from the patient.

3. Patient registration. Data entry errors and omissions can lead to thousands of dollars in lost revenue for an urgent care center. Not only are many insurance claims rejected due to inaccurate information, but incorrect addresses also lead to postal return of patient invoices. When a patient arrives at the urgent care center, the front office should verify that all demographic information is complete, that information reported on forms matches patient identification and insurance cards, and that data are accurately entered into the billing system. If the patient has been seen at the center before, it’s inadequate to ask, “Has your information in the system changed?” Instead, the front desk should have the patient review and initial a printout of address, employment, and insurance information to signify that it is all correct.

4. Collect copayment, deductible, and patient balances. Failure to collect patient financial responsibility prior to treatment too often results in patients “walking out” without paying or “forgetting” their checkbook. Copays should always be collected by the front desk at registration. It’s also a good idea to review the patient’s account and collect any prior balances due before the patient incurs additional charges. If insurance verification shows a deductible, the policy at many centers is for the patient to pay a “deposit” (typically $100 to $150—the cost of an “average” visit) up front and then settle any balances when charges are calculated after treatment. If it turns out after submitting an insurance claim that the patient had already met his or her deductible elsewhere, it’s generally cheaper to mail refund checks than to pursue and write off uncollectable balances.

5. Provide care, document services, and post charges. Thorough documentation is necessary for accurate coding and charge entry and to support insurance claims. While the patient is still in the exam room, the provider should document the patient’s history, physical findings, all diagnoses, services performed, supplies used, prescriptions or tests ordered, and patient instructions. Charges should then be entered into the billing system immediately after the visit; this not only assures timely claims submission, but the provider will be readily available to answer any questions about procedures and coding.

Providers should understand what services are reimbursed by various health plans, and charts should be regularly reviewed to assure the documentation supports the level of service, that non-reimbursed services are limited to what’s medically necessary, and that no money is being left on the table by under-coding or omitting billable codes. Regular chart audits can also identify coding issues resulting in rejected claims.

6. Generate and submit claims correctly. When a third‐party payor rejects a claim, correcting and resubmitting can add two to three weeks to the accounts receivable cycle. Health insurance claims are most often rejected due to missing or inaccurate information, including patient name, subscriber information, and diagnosis and procedure codes.

Many practice management systems include “claim scrubber” functionality that assures all fields have been populated with properly formatted data and that coding, bundling, and procedure information complies with Medicare and/or Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) rules. Since such systems are only as good as the data they contain, following steps 1 through 5 above is essential in assuring accurate information on insurance claims.

7. Monitor, receive, and document insurance reimbursement. After an insurance company processes a claim, it sends an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) detailing what services were billed and how much the insurance company and patient are responsible for paying. To assure receivables are not carried on paid accounts, and to invoice patient balances in a timely manner, the urgent care operator should post EOBs to the patient record immediately upon receipt. To expedite posting, many medical billing applications and insurance carriers support electronic remittance services in which EOB data is sent digitally to the billing system.

When combined with direct deposit, electronic remittance can reduce manual effort in posting while accelerating cash availability.

8. Pinpoint reimbursement problems and appeal denials. Most medical billing platforms offer reports illustrating claims, balances, accounts receivable aging, and frequency of denial codes by provider and payor. These reports should identify which accounts and insurance plans require the most attention.

A pronounced trend involving a particular provider or payor may indicate process issues related to documentation, coding, charge entry, or claims submission. When this occurs, immediate corrective action should be taken to avert future denials. Otherwise, it’s necessary to review each denied claim and determine whether additional information is needed, errors need to be corrected, or if the denial needs to be appealed.

When working balances, start with older claims first for timely filing compliance, then work the largest dollar values.

It’s usually most efficient to concentrate on one payor at a time, engaging the insurance company’s provider services representative or regional executives to address systemic concerns.

Billing representatives should utilize a tickler system to remind them when it is time to follow up on previous contact regarding a claim.

When managing billing staff, consider offering incentive pay based on total collections or call activity to motivate staff to actively pursue—and stay on top of—each individual claim.

9. Invoice the patient. Patient invoices should be sent as soon as the EOB is posted because the sooner an invoice is received by the patient, the more likely and faster it is to be paid. Because patients are less likely to pay medical bills they don’t remember or don’t understand, patient invoices should clearly detail the date of service, services performed, insurance reimbursement received, payments collected at time of service, and the reasons behind any patient balances due.

To achieve a patient-friendly look and feel—and scale economies in production and mailing—many urgent care operators utilize third parties to print and mail invoices.

Accepting credit card payment over the telephone or Internet can also reduce costs and accelerate payment versus requiring patients to write and mail a check.

10. Write-offs and third-party collections. The financial policy should address handling of past-due accounts. Typically, centers automatically write off small patient balances (e.g., less than $5 or $10) for which processing costs exceed potential collections. The process for larger balances should designate time intervals (such as 15, 30, 60, 90, or 120 days) for sending a first invoice, second invoice, warning letter, and then disposing the account to a third-party collections agency. Time may begin accruing either from the date of service or receipt of the EOB indicating the patient is responsible but, in either case, the faster this process occurs, the greater success in collections.

If, after several attempts, the urgent care operator cannot collect from the patient, it may be time to turn the account over to a third-party collections agency. Balances but also typically incur lower fees from the collections agency.

Once final payment has been received or the account has been written off to collections, the charge should be closed out. Carrying aged receivables with little expectation of payment can distort the financial picture provided by the balance sheet.

Cash is the lifeblood of the urgent care business, and an important determinant of a center’s success is that everyone involved in patient service—from the front office to providers and billing staff—understands the issues contributing to high receivables, as well as their individual roles in improving overall collections.

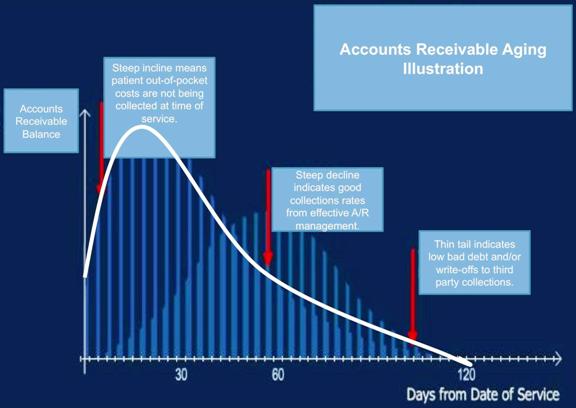

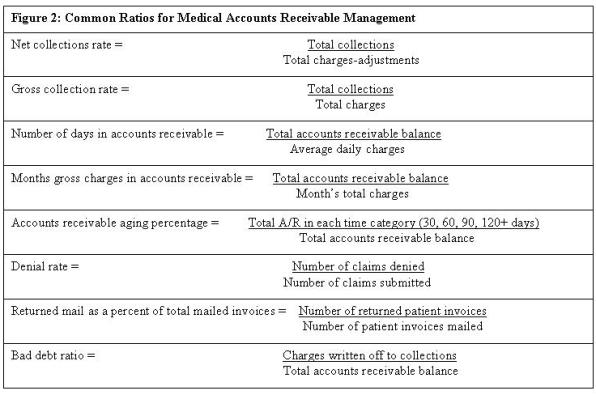

Figure 1 illustrates a healthy billing performance; Figure 2 lists some common ratios used in accounts receivable management. Everyone in the center should understand how collecting patient responsibility at time of service, accurately documenting and submitting charges, and pursuing claims on the backend support the center’s bottom line.

Figure 1: Aging Chart: Accounts Receivable Cycle Indicators

The author is content advisor to the Urgent Care Association of America and vice president of Concentra Urgent

Care in Dallas.