Urgent message: While legal documents may define who in an urgent care is able to legally obligate the company, such as when ordering a service or signing a contract, there are cases where “unauthorized” individuals can still bind the company—meaning the organization must have clear internal policies on signing authority.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc

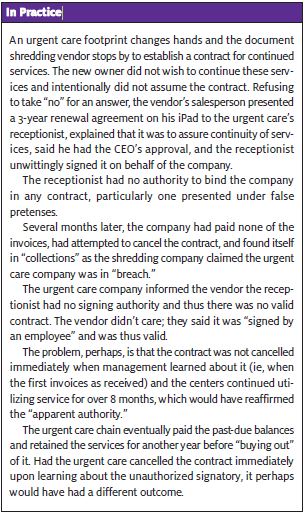

Let’s say that a physician employed at an urgent care facility is working on a Saturday when a toilet backs up. It’s the weekend, so of course, he’s unable to reach management. Frustrated that no one on the staff can resolve the issue, he takes it upon himself to call a buddy who owns a 24-hour plumbing service. The contractor arrives in 10 minutes and gets it fixed in a jiffy.

However, this isn’t a plumber with whom the urgent care has previously done business, and there’s no prior billing arrangement. On Monday morning, the urgent care’s administrative office receives a sizable invoice from the plumber—including his rates and extra charges for after-hours work. When the CFO dismisses the charge as “unauthorized,” the plumber sends her a screenshot showing the precise time and phone number from which the physician ordered the service over the weekend. What happens now?

The plumber can begin collections proceedings and try to get his money. However, he will have to hire a collections attorney and may spend months fighting the charges, eating up valuable time he could be spending with paying customers.

The purpose of the article is to help urgent care owners and operators understand this issue more clearly and to provide suggestions on how to avoid this scenario.

BACKGROUND

Parties who can sign a contract for a company are those who’ve been given the authority to represent their company in contract negotiations. As is we will discuss in detail , this authority can be either actual authority or apparent authority. Establishing and determining who has the proper authority to sign contracts on behalf of a company and bind the business to an obligation is a critical question—as was the case with the weekend plumber—because confusion and ambiguity with this can result in a contract dispute and possible litigation.1

This scenario is not uncommon, as vendors and bill collectors frequently hear that an employee wasn’t authorized to sign an agreement. And how would a vendor arriving at an urgent care on a Saturday afternoon know (and confirm) that a doctor has the authority to sign for the company? Let’s discuss.

WHO HAS SIGNING AUTHORITY?

When a business like an urgent care center is incorporated, it’s considered its own legal entity; as such, the owner can’t simply sign her name on business contracts on behalf of the company. Instead, this is governed by the company’s bylaws, which will state who is an authorized representative and may bind the company by signing an agreement.1

What is ‘Actual Authority’ and ‘Apparent Authority’?

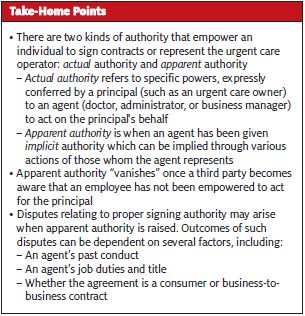

There are two types of authority an individual may have in signing. Urgent care owners and managers should be clear on the differences between the two.

Actual authority refers to specific powers, expressly conferred by a principal (such as an urgent care owner) to an agent (doctor, administrator, or business manager) to act on the principal’s behalf.2

The Second Circuit has stated that actual authority stems from “direct manifestations from the principal to the agent.”3 However, a court may also infer actual authority “from words or [c]onduct which the principal has reason to know indicates to the agent that [s]he is to do the act.”4

Apparent authority is when an agent has been given implicit authority which can be implied through various actions of those whom the agent represents.1 In other words, apparent authority stems from manifestations by the principal to third parties or to the world at large.5 The specific powers of implied or apparent authority depend on the circumstances; they are sometimes determined by the usages and customs of a trade, business, or profession.6 Thus, if a third party enters into a contract with such an agent operating under apparent authority, that contract may still be legally binding on the principal.

It’s important to understand that apparent authority gives rise to agency by estoppel.7 This means that a principal’s representation to a third party that an agent has authority to act on their behalf, when acted upon by that third party by entering into a contract with the agent, operates as an estoppel—this stops the principal from denying the contract is legally binding.6 One court has stated that “[a]pparent authority ends when it is no longer reasonable for the third party with whom an agent deals to believe that the agent continues to act with actual authority.”8

When dealing with a business for most day-to-day purchases, it’s not practical for a vendor to inspect the corporate bylaws to determine who has signature authority. “Apparent authority” enables a vendor to rely on appearances and representations made that the person signing is authorized to do so.

As to the acts of an agent giving rise to liability against the principal, the principal may be held directly liable if the agent “acts with actual authority or the principal ratifies the agent’s conduct.”9

However, it’s important to note that any apparent authority that might otherwise exist “vanishes” with “the third person’s knowledge, actual or constructive, of what the agent is, or what he is not, empowered to do for his principal.”10 Thus, the plumber in our example wouldn’t have much support for an apparent authority argument if he knew his buddy (the urgent care doctor with the broken toilet) couldn’t sign for the company.

SIGNING AUTHORITY DISPUTES

Obviously, most disputes relating to proper signing authority arise when apparent authority is raised. Issues concerning signing authority can be highly fact-intensive. The outcome of a dispute can be dependent on a number of factors, including but not limited to:

- An agent’s past conduct

- An agent’s job duties and title

- Whether the agreement is a consumer or business-to-business contract

Center staff can bind an urgent care company, particularly for minor purchases, even if not authorized by any corporate purchasing policy. When this occurs, a company can’t renege and say the service “wasn’t authorized.” Salespeople take advantage of this, stopping by and getting a receptionist or front office person to “sign” and then claiming the purchase was “authorized.”

How to Avoid This Scenario

Urgent care owners and managers can avoid these disputes by drafting clear corporate policies regarding signing authority.11,12 Also, if an employee is only authorized to sign on behalf of their company in specific circumstances, this can be incorporated into the policy.

The signing authority policy should include a list of definitions; when an individual has authority to execute contracts on behalf of the urgent care; details on purchasing limits; the approval process for expenditures; and if delegations of signature authority is permitted. A code of ethics is also a wise addition.

TAKEAWAY

In the case of our plumber and doctor, either the urgent care owner would settle with the plumber; the doctor would be given an education on actual authority and told to pay out of his own pocket; or the plumber might claim that the doc had apparent authority and seek relief in the courts. Actual authority should be provided in writing to provide evidence of an agent’s authority and to avoid disputes.13

REFERENCES

- UpCounsel. Who can sign a contract for a company: everything you need to know. UpCounsel. Updated October 9, 2020). Available at: https://www.upcounsel.com/who-can-sign-a-contract-for-a-company. Accessed October 6, 2021.

- Kagan J. Actual authority. Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/actual-authority.asp. Accessed October 6, 2021.

- Reiss v Societe Centrale Du Groupe Des Assurs. Nationales. 235 F.3d 738, 748 (2d Cir. 2000).

- United States v Intl. Blvd. of Teamsters. 986 F.2d 15, 20 (2d Cir. 1993).

- Villar v City of N.Y. No. 09-cv-7400 (JSR), 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 123450, at *10 (S.D.N.Y. July 1, 2021).

- BP Oil Corp. v Mabe. 279 Md. 632, 644-45, 370 A.2d 554 (1977).

- McAdory v MNS & Assocs., LLC. No. 3:17-cv-00777-HZ, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 106384, at *13-14 (D. Or. June 7, 2021).

- Meyer v Holley. 537 U.S. 280, 286, 123 S. Ct. 824, 154 L. Ed. 2d 753 (2003).

- Com. Solvents, Inc. v Johnson. 235 N.C. 237, 242, 69 S.E.2d 716 (1952).

- Montclair University. Signing authority policy. Available at: https://www.montclair.edu/policies/all-policies/signing-authority-policy/. Accessed October 6, 2021.

- Carnegie Mellon University. Signature authority for legally binding commitments and documents. Available at: https://www.cmu.edu/policies/financial-management/signature-autority.html. Accessed October 6, 2021.

- Garner BA. Black’s Law Dictionary. 7th ed. Egan MN: Thomson Reuters Legal; 1999.

Read Similar Articles

- Beware Of Urgent Care Contract Clauses On Offshore Vendors, Other Issues

- Safety First When Consummating Relationships With Vendors