Published on

Download the article PDF: When Bell Palsy Is Actually A Stroke A Case Report

Urgent Message: While Bell palsy is the most common diagnosis for patients with unilateral facial weakness/paralysis, it is important for urgent care clinicians to be able to quickly differentiate it from other more serious diagnoses.

Keywords: facial palsy; stroke mimic; Bell palsy; central facial weakness; peripheral facial palsy; urgent care evaluation

Luke Wisniewski, OMS3; Finley Kocher, OMS3; Muhammad Akhtar, MD

Abstract

Introduction: Bell palsy is the most common diagnosis for patients with unilateral facial weakness/paralysis without other neurologic symptoms. However, urgent care clinicians need to differentiate between Bell palsy and stroke in a timely fashion.

Case Presentation: A 73-year-old woman presented to the urgent care with a chief complaint of left-sided facial droop beginning approximately 1 hour before arrival.

Physical Exam: Cranial nerve examination showed mild left facial droop including flattening of the forehead creases, loss of nasolabial fold, and drooping mouth. She had mild dysarthria and 4/5 strength of left upper and lower extremities.

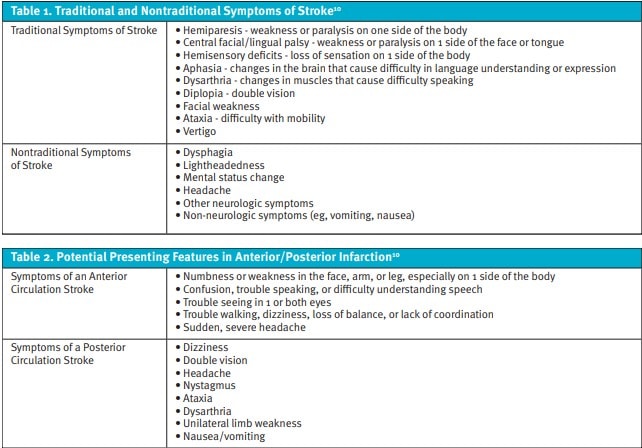

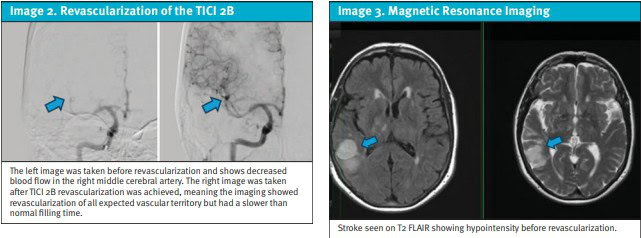

Case Resolution: Given the concerning examination, the patient was referred to a hospital emergency department and diagnosed with a right middle cerebral artery ischemic stroke. She underwent a mechanical thrombectomy with revascularization.

Introduction

Bell palsy affects 1 in 60 people throughout their lifetime.1 It is the most common diagnosis for patients with unilateral facial weakness/paralysis without other neurologic symptoms. Strokes affect more than 795,000 people in the United States each year with 87% being ischemic strokes.2 An ischemic stroke can present with numbness of arms or legs along with difficulty of speech, balance, and/or facial weakness (Table 1). Stroke is a leading cause of disability and the fourth leading cause of death nationally.3It is important for urgent care clinicians to be able to differentiate between Bell palsy and stroke in a timely fashion.

Initial Presentation

A 73-year-old woman presented alone to the urgent care with a chief complaint of left-sided facial droop beginning approximately 1 hour before arrival. She denied arm weakness, leg weakness, numbness, confusion, or slurred speech. The patient had a history of hypertension for which she took hydrochlorothiazide. The patient drank alcohol occasionally, smoked 1-2 packs of cigarettes per day, and denied illicit drug use. She did not endorse any recent falls, trauma, or fever.

Physical Exam

The patient had normal vital signs. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. Cranial nerve examination showed mild left facial droop including flattening of the forehead creases, loss of nasolabial fold, and drooping mouth. She had mild dysarthria, 4/5 strength of the left upper and lower extremities, and 5/5 strength of the right upper and lower extremities. The patient had no motor drift in her arms or legs bilaterally and finger-to-nose testing was normal bilaterally. The exam of her lungs, heart, and abdomen were normal.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for isolated unilateral facial droop includes:

- Bell palsy (idiopathic facial nerve palsy)

- Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic)

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster virus)

- Infection with extension to face (eg, otitis media, mastoiditis, Lyme disease, mucormycosis)

- Tumor (eg, acoustic neuroma, parotid gland tumor)

- Multiple sclerosis

Medical Decision Making

Initially, based on the patient’s history, the urgent care clinician suspected a diagnosis of Bell palsy. However, the neurological exam in this case also revealed decreased motor function in the left upper and lower extremities, along with dysarthria. When the patient’s husband arrived, he provided additional history, stating that the patient had acute changes in her behavior, including leaving for work later than usual and driving her car into the steps at the end of the driveway. These behaviors had never happened before. He also noticed mild confusion and indicated that when her glasses were crooked, she made no effort to correct them even after he pointed it out. In addition, he noted she wasn’t using her left arm correctly and struggled with balance. With the new detailed history from the husband and subtle findings noted on her neurological exam, this changed the primary working diagnosis from Bell palsy to stroke.

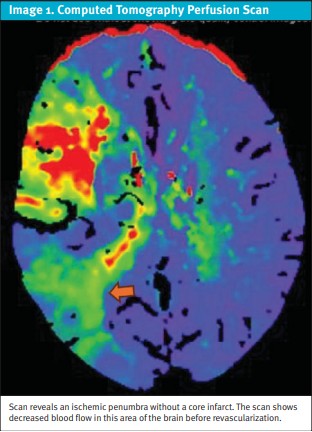

The patient was evaluated in the emergency department (ED), where a stroke alert was called, as the onset of symptoms occurred within 24 hours. On arrival, the patient had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) of 7. Labs were within normal limits including a fingerstick blood sugar, and a computed tomography (CT) of the brain did not show any evidence of hemorrhage. However, CT angiography (CTA) found a large vessel occlusion in the M2 branch of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) (Image 1). The patient was not a candidate for thrombolytic treatment due to her last known normal state being greater than 4.5 hours prior, but she remained a candidate for endovascular treatment.

Discussion

The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) is the seventh paired cranial nerve and is predominantly a motor nerve innervating the muscles of facial expression, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the stylohyoid muscle, with special sensory fibers providing taste sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. It also has parasympathetic fibers to many of the glands of the head and neck, including the lacrimal glands. The portion of the facial nerve that innervates the lower two-thirds of the face originates in the contralateral motor cortex, while the facial nerve that innervates the upper one-third of the face originates in both the contralateral and ipsilateral motor cortex.4

Lesions that damage the upper motor neurons in the motor cortex, such as acute ischemic strokes, will result in contralateral facial weakness of the lower face only, with preservation of the muscles of the upper face. Patients will have a weak smile but will be able to close their eye tightly and wrinkle their forehead symmetrically.5 Conversely, a lower motor neuron lesion like Bell palsy typically leads to complete hemiparalysis of the face as it affects all branches of the facial nerve on one side of the face.4 A central facial palsy can also affect the corticobulbar tract and present with sparing of the upper third of the face. 5

The most common cause of a central facial nerve palsy is a stroke.6 More dangerously, a large enough MCA stroke, as seen in this case, can affect both the upper and lower quarters of the face. A stroke this large would be expected to present with other symptoms such as personality changes or extremity paralysis. Strokes affect men and women of all ages, so it is important to take a good clinical history and perform a physical exam. Strokes may present differently in different people with presentations with both traditional and nontraditional signs of stroke (Table 1). Women present with non-traditional signs of stroke more commonly than men.7 The middle cerebral artery distribution is the most common stroke location.8 Additionally, common stroke symptoms include headache, gait disturbances, speech deficits, hemianopia, paresis, and sensory deficits. 9 Warning signs are important for quickly assessing patients. Clinical neurologic deficits alone should not be used to localize stroke due to overlapping features of anterior circulation infarction and posterior circulation infarction and should be used in conjunction with imaging (Table 2).10

Facial nerve palsy (Bell palsy) is a consideration with hemifacial paresis or paralysis without a known cause. This partially or fully hinders the patient’s ability to move the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. Patients have also reported diminished taste, dryness of the eyes or mouth, or changes in hearing.11 Although Bell palsy is often idiopathic, potential causes include herpes zoster virus, tumors, Lyme disease, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, or several other causes.12 Bell palsy has an acute onset, peaking between 24 and 72 hours. Importantly, Bell palsy is rare and a diagnosis of exclusion, only given once other medical etiologies are ruled out.

The urgent care clinician needs to ask the patient about the duration and onset of symptoms and inquire about recent changes in behavior. The clinician should also check orientation to person, place, and time. Family members often notice changes in mental status that would otherwise be missed, as was discovered when this patient’s husband arrived and revealed important information that the patient did not share. Additional history about focal neurological symptoms, such as unilateral numbness or weakness of the extremities, slurred speech, facial droop or confusion, should be obtained. A sudden onset of headache is concerning for subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Unintentional weight loss could indicate a primary brain tumor or metastatic disease. A fever may indicate an infectious etiology such as meningitis or brain abscess. The use of substances could cause confusion or might contribute to difficulty with obtaining an adequate history. For example, a patient with alcohol use disorder who had head trauma from a fall may not remember the events.

Subtle neurological deficits can easily be overlooked by the clinician, leading to misdiagnosis and poor patient outcomes. A physical exam for a suspected Bell palsy should include a neurological exam with a complete cranial nerve exam. Additionally, patients should be asked to move their eyebrows, close their eyes, show their teeth, frown and purse their lips. The clinician should check for strength and sensation of the extremities as well as perform cerebellar testing, such as a finger-to-nose test.

Patients with concerning histories, other neurological symptoms, and/or the ability to tightly close their eyes and wrinkle their forehead should be further evaluated for a central lesion. Patients without these signs do not need additional testing to diagnose Bell palsy.

Case Resolution

The patient had a CT perfusion scan revealing an area of decreased blood flow that was potentially salvageable (Image 1). Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a right MCA stroke without a known etiology before revascularization (Image 2). After neurosurgery was consulted, the patient was taken to the operating room for mechanical thrombectomy with successful revascularization (Image 3). The patient was discharged home with aspirin 81 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, and a cardiac monitor for further evaluation. At the time of discharge, her NIHSS was 1.

Ethics Statement

Informed consent for publication of this case was not able to be obtained as the patient did not return any communication. The details and demographics of the case have been altered to protect the patient’s privacy.

Takeaway Points

- History and physical examination are critical when differentiating Bell palsy and stroke; if there are focal neurologic symptoms in addition to the facial palsy, rule out stroke.

- A peripheral nerve cause of hemifacial weakness will affect both the upper and lower face. Central causes of hemifacial weakness tend to spare the upper face unless both motor hemispheres are affected.

Manuscript submitted June 20, 2025; accepted November 11, 2025.

References

- Holland J. Bell’s palsy. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008; 2008:1204. Published 2008 Jan 2.

- Tsao CW, et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023 Feb 21;147(8):e93-e621. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123. Epub 2023 Jan 25. Erratum in: Circulation. 2023 Feb 21;147(8):e622. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001137. Erratum in: Circulation. 2023 Jul 25;148(4):e4. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001167. PMID: 36695182; PMCID: PMC12135016.

- Ahmad FB, Anderson RN. The Leading Causes of Death in the US for 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1829–1830. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.5469

- Yang SH, Park H, Yoo DS, Joo W, Rhoton A. Microsurgical anatomy of the facial nerve. Clin Anat. 2021 Jan;34(1):90-102. doi: 10.1002/ca.23652. Epub 2020 Aug 21. PMID: 32683749.

- Bhatti MT, Schiffman JS, Pass AF, Tang RA. Neuro-ophthalmologic complications and manifestations of upper and lower motor neuron facial paresis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010 Nov;10(6):448-58. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0143-1. PMID: 20835929.

- Induruwa I, Holland N, Gregory R, Khadjooi K. The impact of misdiagnosing Bell’s palsy as acute stroke. Clin Med (Lond). 2019 Nov;19(6):494-498. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2019-0123. PMID: 31732591; PMCID: PMC6899254.

- Berglund A, Schenck-Gustafsson K, von Euler M. Sex differences in the presentation of stroke. Maturitas. 2017 May;99:47-50. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.02.007. Epub 2017 Feb 16. PMID: 28364868.

- Zhang K, Li T, Tian J, Li P, Fu B, Yang X, Liu L, Zhao Y, Lu H, Zhao P, Bu K, Li Z, Yuan S, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Guo L, Liu X. Subtypes of anterior circulation large artery occlusions with acute brain ischemic stroke. Sci Rep. 2020 Feb 26;10(1):3442. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60399-3. PMID: 32103113; PMCID: PMC7044197.

- Rathore SS, Hinn AR, Cooper LS, Tyroler HA, Rosamond WD. Characterization of incident stroke signs and symptoms: findings from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 2002 Nov;33(11):2718-21. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000035286.87503.31. PMID: 12411667.

- Tao WD, et al.. Posterior versus anterior circulation infarction: how different are the neurological deficits? Stroke. 2012 Aug;43(8):2060-5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652420. Epub 2012 Jun 7. PMID: 22678088.

- Baugh, R.F., Basura, G.J., Ishii, L.E., Schwartz, S.R., Drumheller, C.M., Burkholder, R., Deckard, N.A., Dawson, C., Driscoll, C., Gillespie, M.B., Gurgel, R.K., Halperin, J., Khalid, A.N., Kumar, K.A., Micco, A., Munsell, D., Rosenbaum, S. and Vaughan, W. (2013), Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell’s Palsy. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 149: S1-S27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813505967

- Tiemstra, Jeffrey D., and Nisha Khatkhate. Bell’s Palsy: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Phys. 2007;76(7):997–1002. PMID: 17956069.

- Higashida RT, et al. Technology Assessment Committee of the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology; Technology Assessment Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003 Aug;34(8):e109-37. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000082721.62796.09. Epub 2003 Jul 17. Erratum in: Stroke. 2003 Nov;34(11):2774. PMID: 12869717.

Author Affiliations: Luke Wisniewski, OMS3, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. Finley Kocher, OMS3, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. Muhammad Akhtar, MD, Adena Regional Medical Center in Chillicothe, Ohio. Authors have no relevant financial relationships with any ineligible companies.

Read More

- Delayed-Onset Facial Nerve Palsy Following Post-Auricular Gunshot Wound: A Case Report

- Rash, Facial Palsy, and Ear Pain