Published on

Download the article PDF: The Impact Of Parental Pressure On Providers Practicing In Pediatric Urgent Care

Urgent Message: Pediatric urgent care providers commonly experience pressure to satisfy parental expectations, which may alter clinical decision making, increase stress levels, and/or impart barriers to administering quality care.

Keywords: parental pressure; antibiotic prescribing; shared decision-making; pediatric urgent care; patient satisfaction; clinical decision-making

Daniel Moscato, MS, PA-C; Sara Winter, MS, PA-C

Abstract

Background: Patient-centered care focuses on strengthening patient participation in their own healthcare. Although advantages to such care exist, intended shared decision making between providers and their patients has been paradoxically documented to impart negative impacts on the providers administering the care. The purpose of this study was to identify to what extent the pressure to satisfy parental requests/expectations alters pediatric urgent care providers’ clinical decision making, increases stress level, and/or imparts barriers to administering quality, evidence-based medicine.

Methods: This survey-based study included providers (physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) who worked in a pediatric urgent care for >6 months. Survey questions focused on the frequency at which respondents felt pressured to satisfy specific parental requests/expectations and to what extent such pressure altered their ultimate work-up and/or management plan(s). Respondents were also asked how parental pressures add stress to their roles as providers, impart a strain on interactions with parents/patients, diminish decision-making autonomy, and alter ability to render quality, evidence-based medical care. Responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics and independent samples t-tests.

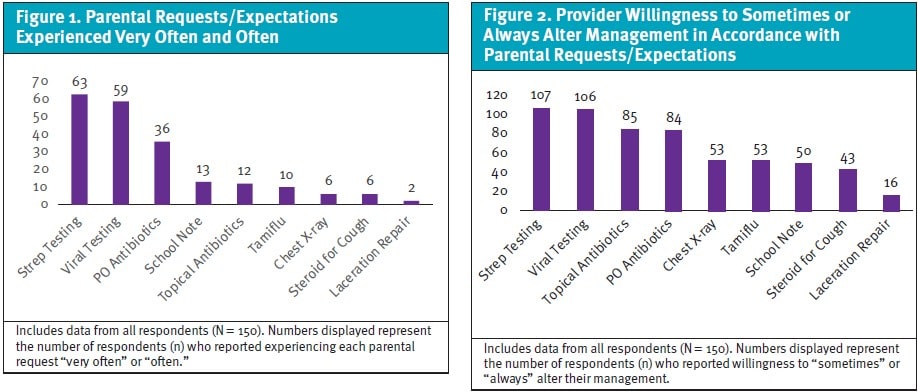

Results: A total of 150 surveys were completed. Respondents reported experiencing the highest frequency of pressure (very often or often) to satisfy parental requests/expectations for lab testing (viral [63/150], strep [59/150]) and antibiotics (oral [36/150], topical [12/150]). High frequency of pressure was also identified for school notes (13/150). Respondents were also more likely to admit changing their management plans based on parents’ requests/expectations for lab testing (viral [107/150], strep [106/150]) and antibiotics (topical [85/150], oral (84/150]). Seventy-seven percent of all respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the pressure to satisfy parental requests/expectations adds stress to their roles as providers. Of those who reported a greater degree of stress, they also reported an overall greater strain on parent/patient interactions and diminished decision-making autonomy relative to respondents with lower stress (p = <0.001, p = 0.003, respectively). Most respondents (91%) either agreed or strongly agreed that they still felt they could provide quality, evidence-based medical care to their patients despite such pressure.

Conclusion: Pediatric providers practicing in the urgent care setting commonly experience pressure to satisfy parental requests/expectations, which oftentimes alters their ultimate work-up and management plans. Despite such pressures adding stress to their roles, providers must continue providing quality, evidence-based medical care.

Introduction

In an effort to strengthen patients’ participation in their own healthcare, approaches such as family-, child-, patient-, and person-centered care have been advocated in recent decades.1 These modalities of care encourage active collaboration and shared decision-making between patients and providers to design and manage a customized, comprehensive care plan.2Advantages of this shared decision-making include improved satisfaction scores among patients and their families, enhanced reputation of providers among healthcare consumers, and increased financial margins throughout the continuum of care.2

However, such shared decision-making has also paradoxically been documented to impart potential negative impacts on providers administering the care, including a strain on patient-provider interactions, diminishing a provider’s personhood and/or decision-making autonomy, and increasing overall resource demand/cost.1 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that perceived parental and/or patient expectations may ultimately alter a provider’s rendered treatment plan.3,4

The aim of this research study was to assess to what degree providers practicing in a pediatric urgent care setting felt pressured by parental requests/expectations (direct or indirect) to render a specific treatment plan or provide further work-up/testing for their child when not necessarily medically indicated. Additionally, the study aimed to assess to what extent such pressures have altered providers’ clinical decisions in specific clinical scenarios. Additionally, researchers aimed to assess how such pressures may alter providers’ stress, parental/patient interactions, decision-making autonomy, counseling/education efforts, and overall quality of care.

Methods

Selection and Description of Participants

This was a survey-based study approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York Institute of Technology (Study ID NYIT IRB-2025-231), with the stipulation of acquiring permission from the utilized pediatric urgent care clinics for circulation of our electronic surveys to employees and consent from the survey participants. Providers (physicians, physician assistants [PAs], and nurse practitioners [NPs]) were included if currently employed in a pediatric urgent care setting (per diem, part-time, or full-time), having worked regularly (at least 18 hours/month, on average) in this setting for at least 6 months prior to survey issuance.

Data Collection and Measurements

The survey was distributed electronically using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) to 644 providers employed at a pediatric urgent care with national presence. Three reminders were sent at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after initial survey distribution.

Following informed consent and evaluation to meet inclusion criteria, survey participants first answered questions pertaining to their demographics, including: age; gender; primary race; ethnicity; professional title; length of practice in a pediatric urgent care setting; hours/month of practice in a pediatric urgent care setting; and residence/state of primary practice.

Next, using a Likert scale, respondents were asked to report over the past 6 months of practice, on average, how frequently (never, rarely [1-2 times/month], sometimes [3-5 times/month], often [5-10 times/month], very often [>10 times/month]) they felt pressured to satisfy parental requests/expectations to:

- Prescribe an oral (PO) antibiotic when not medically indicated

- Prescribe a topical antibiotic when not medically indicated

- Administer and/or prescribe a steroid for a cough when not medically indicated

- Order and/or perform strep testing when not medically indicated

- Order and/or perform a viral test when not medically indicated

- Prescribe an antiviral medication when not medically indicated

- Order and/or perform a chest x-ray when not medically indicated

- Perform a complex laceration repair despite discussing the risks of scarring/poor cosmetic outcome

- Write an excuse note for school when not medically necessary

If respondents answered anything other than “never” to any 1 of the aforementioned scenarios on the Likert scale, follow-up questioning asked how frequently (never, sometimes, or always) the pressure to satisfy that particular parental request/expectation altered their management plans.

In final questioning, using a Likert scale, respondents were asked if they strongly agreed, agreed, neither agreed or disagreed, disagreed, or strongly disagreed that parental requests/expectations:

- Add stress to their roles as providers

- Impart a strain on interactions with parents/patients

- Diminish their decision-making autonomy

Additionally, respondents were asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed that parents are amenable to education/counseling when management plans do not align with requests/expectations and their overall confidence in being able to satisfy parental requests/expectations while still providing quality, evidence-based medical care.

Statistics

Survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics and independent samples t-tests. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools. Data analysis was completed using JASP, version 0.19.3.

Results

Of 644 surveys delivered, a total of 162 surveys were initiated, 12 surveys were partially completed and excluded from the final analysis, resulting in a total of 150 completed surveys (response rate 23%). The demographics of the respondents are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Survey Respondent Demographics

| Demographic/Characteristic | n =* |

| Age 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 > 60 | 8 48 57 28 9 |

| Gender Female Male Non-Binary Unanswered | 119 29 1 1 |

| Primary Race American Indian/Alaska Native Asian Black or African American Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander White Other Prefer Not to Answer Unanswered | 1 15 12 1 105 7 8 1 |

| Ethnicity Hispanic or Latino Not Hispanic or Latino Other Prefer Not to Answer Unanswered | 11 118 14 5 2 |

| Professional Title Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine Medical Doctor Nurse Practitioner Physician Assistant/Associate Unanswered | 4 73 41 31 1 |

| Length of Practice in Pediatric Urgent Care Setting 6-12 Months 12-18 Months 18-36 Months 3-5 Years > 5 Years Unanswered | 17 7 25 31 69 1 |

| Hours of Practice in Pediatric Urgent Care Setting (Per Month) 18-24 Hours/Month 24-48 Hours/Month 48-96 Hours/Month 96-144 Hours/Month > 144 Hours/Month | 20 21 27 51 3 1 |

| U.S. State of Practice California Connecticut District of Columbia Florida Illinois Massachusetts Maryland North Carolina New Jersey New York Pennsylvania Tennessee Texas Virginia Unanswered | 5 3 2 9 2 5 17 7 18 50 3 1 14 4 10 |

| *Demographic/characteristic data from a total (N) of 150 respondents. | |

Of all respondents, most reported experiencing the highest frequency of pressure (very often or often) to satisfy parental requests/expectations for lab testing (strep, viral) and antibiotics (oral, topical) (Figure 1). Additionally, most respondents admitted to sometimes or always altering their management plans for lab testing and antibiotic prescriptions in response to such requests/expectations (Figure 2). Those who reported experiencing greater pressure (very often and often) to satisfy parental requests/expectations were more likely to alter their management plans, especially when prescribing topical antibiotics (p = 0.047), and when ordering chest x-rays (p = 0.047), strep testing (p = 0.006), and viral testing (p = < 0.001) (Table 2).

Of all respondents, 77% either agreed or strongly agreed that the pressure to satisfy parental requests/expectations adds stress to their roles as providers, and these same respondents reported a greater strain on parent/patient interactions and a greater hindrance on decision-making autonomy, relative to those who reported less stress (p = <0.001, p = 0.003, respectively). Sixty-six percent of respondents, however, agreed or strongly agreed that parents seemed to be amenable to education and counseling, even when their work-up/management plans did not align with initial parental requests/expectations. And, despite admitted stressors, 90% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that they could still provide quality, evidence-based medical care to their patients.

Table 2. Willingness to Alter Management Between Respondents With Lower Reported Parental Requests/Expectations (Group A) vs Higher Reported Parental Requests (Group B)

| Request/Expectation | Group | n* | Mean (Change in Management)** | Standard Deviation (Change in Management/Plan) | Change in Management/Plan Two-tailed, Independent Samples T-Test (A < B)*** |

| PO Antibiotics | A | 83 | 0.831 | 0.581 | p = 0.958 |

| B | 36 | 0.639 | 0.487 | ||

| Topical Antibiotics | A | 102 | 1.000 | 0.426 | p = 0.047 |

| B | 12 | 0.745 | 0.501 | ||

| Steroid for Cough | A | 68 | 0.691 | 0.675 | p = 0.534 |

| B | 6 | 0.667 | 0.516 | ||

| Viral Testing | A | 79 | 0.785 | 0.601 | p = < 0.001 |

| B | 59 | 1.186 | 0.673 | ||

| Strep Testing | A | 74 | 0.838 | 0.620 | p = 0.006 |

| B | 63 | 1.143 | 0.644 | ||

| Chest X-Ray | A | 75 | 0.720 | 0.627 | p = 0.046 |

| B | 6 | 1.167 | 0.408 | ||

| Antiviral | A | 69 | 0.783 | 0.639 | p = 0.173 |

| B | 9 | 1.000 | 0.707 | ||

| Laceration Repair | A | 37 | 0.486 | 0.651 | p = 0.489 |

| B | 2 | 0.500 | 0.707 | ||

| School Note | A | 68 | 0.779 | 0.750 | p = 0.165 |

| B | 13 | 1.000 | 0.707 |

*n (out of 150 respondents).

**Mean change in management between Group A and Group B is based on the average Likert scale selection of Never (0), Sometimes (1), or Always (2).

***p-values represent the results of a 2-tailed, independent samples T-test between Group A and Group B for each specific request/expectation.

There were no statistically significant differences in the responses between providers of varying ages, genders, race, ethnicity, professional titles, greater clinical experience (> 5 years) and less clinical experience (< 5 years), greater hours of practice (> 96 hours/month) and fewer hours of practice (< 96 hours/month), or region of practice.

Discussion

We aimed to investigate how the clinical decision making of providers practicing in a pediatric urgent care setting may be altered by parental requests/expectations and how such requests/expectations may add stress to providers’ roles and hinder their perceived ability to render quality, evidence-based medical care to their patients. Although research on the benefits of patient-centered care exists, there remains a gap in knowledge of how such care affects the providers rendering it. Researchers sought to expand this knowledge by analyzing data acquired from the perspectives of pediatric urgent care providers.

Respondents reported most frequently experiencing parental requests for antibiotics (oral, topical) and, likewise, were admittedly more likely to alter their management plans secondary to such requests. As highlighted by the American Academy of Pediatrics, antibiotics are the most common class of medications prescribed to children, and although antibiotic therapy has saved a countless number of lives, their overuse can cause harm (ie, antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infections, and other drug-related adverse events).5 Across a multitude of settings, the institution of antibiotic stewardship programs has been promoted, encouraging use of antibiotics only when necessary and at the most appropriate spectrum of activity, dose, route, and duration of therapy to optimize clinical outcomes while minimizing undesirable consequences.5

Additionally, a variety of stewardship strategies have been implemented in ambulatory settings, some of which specifically focus on clinician/parent communication training and clinician/parent education.6 Taking additional time to educate parents about the natural course of viral and bacterial infections can foster a better understanding of expectations, and it has been estimated that unnecessary antibiotic prescribing in an ambulatory setting could be safely reduced by 30%.7

Of all the survey respondents, 66% either agreed or strongly agreed that parents seemed to be amenable to education and counseling, even when their work-up/management plan(s) did not align with initial parental requests/expectations. If providers continue to diligently utilize recommended testing and treatment algorithms and take the time to educate/counsel parents, despite conflicting requests/expectations, parents may be more accepting of the ultimate management plan.

Additionally, respondents reported most frequently experiencing parental requests for lab testing (viral, strep) and, likewise, were admittedly more likely to alter their management plans secondary to such requests. Timely and accurate diagnosis of respiratory virus and strep infections in ambulatory settings has the potential to optimize downstream use of limited healthcare resources (ie, antibiotics, antivirals, ancillary testing, and inpatient/emergency department beds), so long as cost-effective methodologies for ordering/performing these tests are accounted for (ie, which patients should be tested, what testing should be performed, and the turnaround time necessary to achieve the desired post-testing outcomes), according to a study presented by Pinsky and Hayden in 2019.8 Viral respiratory infections are especially common in children, and practice guidelines do not recommend testing for typical viral illnesses. However, despite the fact that results often do not impact care, nasopharyngeal swabs for viral testing are frequently performed.9 As identified in our study, parental pressure may be contributing to this.

Another study by Ahluwalia found that rapid strep tests were ordered for patients < 3 years of age, a rare etiology for pharyngitis and one very often without sequelae in this same age group.10 Both aforementioned studies promote the use of clinical decision pathways to greater support the medical decision making of providers and more importantly highlight a resulting reduction of ordered tests without significant negative patient outcomes or caregiver grievance.9.10

Regarding the pressure to satisfy parental requests/expectations, one-third of physicians practicing in an academic children’s medical center were more likely to order tests, medications, and/or consultations due to the pressure to acquire higher patient satisfaction scores, according to a study by Sas.4 Additionally, one-third of those studied agreed that such patient satisfaction surveys contribute to burnout and make it difficult to practice meaningful medicine.4

Despite most of our respondents agreeing that parental requests add stress to their roles as providers and impart a strain on parental/patient interactions, most promisingly agreed or strongly agreed that parents are amenable to education/counseling and that they can still provide quality, evidence-based medical care to their patients in the pediatric urgent care setting.

Limitations

This study has notable limitations. Given that this study surveyed providers all working within a single urgent care company, there is potential that our results may not be generalizable to different populations/settings. Furthermore, this survey is subject to recall bias as questions relied on respondents recall of patient encounters over a 6-month period. Additionally, over this 6-month period, frequencies may have been impacted by geographic region due to parental request/expectation differences from region-specific outbreaks of illnesses. There also may be a social desirability response bias—in which respondents may have answered questions in a manner they believed would be viewed favorably by others, rather than providing their true thoughts or behaviors—especially when respondents were asked to state how often they changed treatment/management plans secondary to parental requests/expectations. Future research would ideally include a more robust sample size and one that includes providers practicing in multiple settings (outpatient facilities, emergency departments, and additional urgent cares) to further understand the impact on patient care from pressures experienced by providers.

Conclusion

In this study of pediatric urgent care providers, most respondents reported the greatest pressure from parents to prescribe antibiotics and/or order lab testing and tended to follow through with such requests. Most providers agreed that the pressure to satisfy such requests adds stress to their roles, a strain on parent/patient interactions, and decreases their overall decision-making autonomy. Providers can utilize education/counseling of parents/patients to address those pressures to ensure they provide quality, evidence-based medical care.

Manuscript submitted June 8, 2025; accepted December 12, 2025.

References

- Summer Meranius M, Holmström IK, Håkansson J, Breitholtz A, Moniri F, Skogevall S, Skoglund K, Rasoal D. Paradoxes of person-centered care: a discussion paper. Nurs Open. 2020;7(5):1321-1329. doi:10.1002/nop2.520

- The New England Journal of Medicine Brief. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. Published 2017. doi:10.1056/CAT.17.0559

- Sirota M, Round T, Samaranayaka S, Kostopoulou O. Expectations for antibiotics increase their prescribing: causal evidence about localized impact. Health Psychol. 2017;36(4):402-409. doi:10.1037/hea0000456

- Sas DJ, Absah I, Phelan SM, et al. Patient satisfaction scores impact pediatrician practice patterns, job satisfaction, and burnout. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2022;62(7):769-780. doi:10.1177/00099228221145270

- Gerber JS, Jackson MA, Tamma PD, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2021;147(1):e2020040295. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-040295

- Mangione-Smith R, Zhou C, Robinson JD, Taylor JA, Elliott MN, Heritage J. Communication practices and antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infections in children. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):221-227. doi:10.1370/afm.1785

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864-1873. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4151

- Pinsky BA, Hayden RT. Cost-effective respiratory virus testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:e00373-19. doi:10.1128/JCM.00373-19

- Ostrow O, Savlov D, Richardson SE, Friedman JN. Reducing unnecessary respiratory viral testing to promote high-value care. Pediatrics. 2022;149(2):e2020042366. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-042366

- Ahluwalia T, Jain S, Norton L, Meade J, Etherton-Still J, Myers A. Reducing streptococcal testing in patients <3 years old in an emergency department. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190174. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0174

Author Affiliations: Daniel Moscato, MS, PA-C, PM Pediatric Care, New York; New York Institute of Technology. Sara Winter, PA-C, PM Pediatric Care, New York; Molloy University. Authors have no relevant financial relationships with any ineligible companies.