Published on

Download the article PDF: Progressive Ankle Pain In A 12 Year Old Male A Case Report Of Osteomyelitis

Urgent Message: While most pediatric musculoskeletal complaints are usually benign and self-limited, the urgent care clinician must consider more serious underlying causes of pain in the differential diagnosis.

Keywords: pediatric osteomyelitis; atraumatic ankle pain; limping child; bone infection; ESR; CRP; MRI diagnosis

Erin Loo, PA-C, MHA, FCUCM

Abstract

Introduction: Pediatric patients commonly present to urgent care (UC) with musculoskeletal complaints. However, a wide differential should be considered, including musculoskeletal injury, synovitis, autoimmune conditions, cellulitis, avascular necrosis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and neoplasm.

Case Presentation: A 12-year-old male with no past medical history presented to UC with 1 day of nontraumatic right ankle pain.

Physical Exam and Imaging: The patient’s exam findings included mild lateral right ankle edema, slight discomfort with dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, and antalgic gait favoring the right ankle. There was no erythema, abrasion, or ecchymosis. The ankle x-ray was negative.

Case Resolution: The initial diagnosis was right ankle sprain, and treatment included supportive care. He had worsening symptoms over the next 5 days leading to an emergency department visit on day 5. The patient was transferred to a children’s hospital where magnetic resonance imaging revealed osteomyelitis and subperiosteal abscess in the distal fibula.

Conclusion: UC clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for more complicated and significant causes of musculoskeletal pain in children.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal complaints in pediatric patients are frequent in the urgent care (UC) setting, and the common causes include sprains and strains, overuse injuries, synovitis, and growing pains.[1] Emergency department (ED) data from 2002 to 2006 shows an incidence of ankle sprain of 7.2 per 1,000 in the adolescent population, and more than 50% of ankle sprains occurred in those aged 10-24 years.[2] This is likely an underestimation of the total rate as most patients do not present to the ED with ankle sprains, preferring primary care, sports medicine, or urgent care clinics.2 Inflammatory conditions should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of musculoskeletal complaints including juvenile arthritis, post-infectious arthralgias, soft tissue infections, osteomyelitis, bone cancers, leukemia, and tumors.1,[3]

Case Presentation

A 12-year-old male with no past medical history presented to the UC with a chief complaint of atraumatic right ankle pain for 1 day. The patient reported mild pain with weight bearing and no known injury, but he did play on a large inflatable water slide 2 days before the pain began. The mother noted the possibility of twisting his ankle without realizing it while playing. He denied history of joint problems and previous injury to the right ankle. The patient denied fever, nausea, vomiting, skin redness, or skin trauma. The patient did not use any treatment for his ankle pain before presenting to the UC. The patient denied recent infections, surgeries, or injuries within the last 6 weeks. Family history was significant for a brother with type 1 diabetes mellitus and a sister with morphea (localized scleroderma).

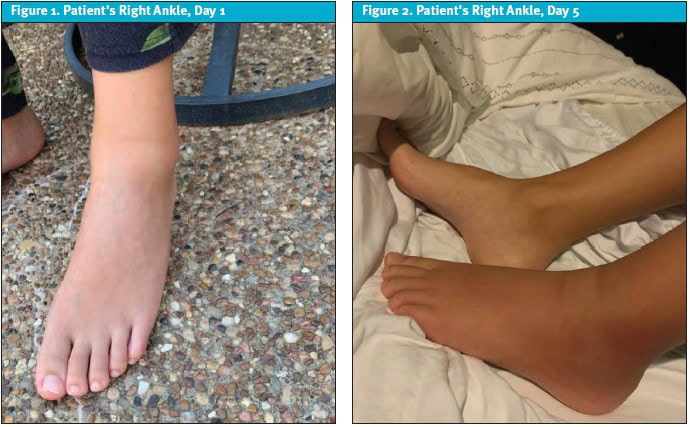

The physical exam revealed mild edema and tenderness to palpation of the lateral right ankle, full range of motion with mild discomfort, which was more significant with dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The skin was normal and intact without erythema (Figure 1). The right ankle x-ray was normal.

Diagnosis

Initially, the patient was diagnosed with right ankle sprain and treated with conservative management including ibuprofen, rest, ice, compression, and elevation. A referral to sports medicine was provided if no improvement was noted within 1 week.

Case Continuation and Resolution

The mother contacted the clinic 2 days later reporting worsening pain despite nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient was evaluated by sports medicine that day, and a repeat x-ray and complete blood count (CBC) were both normal. The physical exam was unchanged. Sports medicine agreed with the assessment of ankle sprain, prescribed a pneumatic boot, and continued with conservative care.

The mother contacted the UC on day 5, saying her son was crying at night from pain with the inability to bear weight, and there was redness and swelling over the ankle (Figure 2). She was advised to proceed to ED for further evaluation of her son.

The ED team repeated ankle x-rays and performed lab testing including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), uric acid, and a rheumatology panel. The x-ray was normal, and bloodwork revealed a mildly elevated CRP. The children’s hospital was consulted, and the patient was transferred for further work-up.

At the hospital, the patient was given morphine and ondansetron. Ultrasound (US) of the right lower extremity was significant for cellulitis and fluid collection. The patient was started on empiric IV antibiotics, and orthopedics was consulted. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed distal fibula osteomyelitis with subperiosteal abscess, and the patient was taken to surgery (Figure 3). Following surgical debridement, IV antibiotics were administered for 5 days.

Cultures collected during the procedure were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The patient was discharged home on day 6 with cephalexin and recovered well with no complications. While no source for infection was identified, the hospital team speculated it was related to minor trauma that allowed for hematogenous spread and seeding of the distal fibula.

Discussion

Osteomyelitis is the result of a microbial infection in the bone leading to pain, inflammation, and damage to the bone.[4] This discussion focuses on acute osteomyelitis; however, it is worth noting that osteomyelitis can be classified as acute (symptoms less than 2 weeks), subacute (symptoms 2 weeks to 3 months), and chronic (symptoms greater than 3 months).1

Osteomyelitis in the pediatric population can be challenging with delays in diagnosis occurring secondary to non-specific symptoms, increasing the risk for long-term morbidity.1,[5] In a study of 211 pediatric patients who presented to the ED, more than 60% of patients ultimately diagnosed with acute osteomyelitis had multiple visits to primary care, urgent care, or the ED before the diagnosis was made.[6] In another study, among pediatric patients presenting to the ED with fever and a painful limb, the initial diagnosis was consistent with the definitive diagnosis only 42% of the time, and 40% of patients had multiple ED visits before acute osteomyelitis was diagnosed.[7] The average time from onset of symptoms to hospital admission is reported to be 4-5 days.6,[8] There is a lack of consensus and expert guidelines for diagnosis, compounding the difficulty in achieving a definitive diagnosis.

In 1 study, 10% of patients with a S. aureus bone or joint infection experienced long-term complications including chronic osteomyelitis, growth arrest, avascular necrosis, chronic dislocation and pathologic fracture.[9] These complications were more common with delayed source control, prolonged fever of >4 days, and more virulent strains of S. aureus.9

Epidemiology

Osteomyelitis incidence in children in the United States is 2-13 per 100,000 annually.5 The ratio between males and females is 2:1, possibly because of a higher likelihood of trauma in males.5 Infections are most common in patients under the age of 5.5

The epidemiology of osteomyelitis is changing with 1 study noting a 2.8-fold increase in infections over the last 20 years.[10] Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is likely implicated.10 Certain conditions such as immunocompromise, indwelling devices, or sickle cell disease are considered risk factors.[11],[12]

Pathophysiology

The source of osteomyelitis is typically from hematogenous spread from a distant infection, transient bacteremia, or microtrauma.7 Spread of bacteria from adjacent infections and inoculation by penetrating trauma can also be sources of infection.1

Most cases of osteomyelitis occur in the metaphysis of the long bones because of their vasculature.[13] While the vasculature is robust, the blood can pool leading to bacterial seeding during times of transient bacteremia.13 The most common sites of infection include the bones of the lower extremities and the long bones,4 especially the femur (27%) and tibia (26%).[14]

While MSSA is the most common causative agent, other bacteria of significance are group B Streptococcus and E. coli, especially in neonates, and pseudomonas in those with a history of puncture wounds or penetrating trauma.5 MRSA and Kingella kingae (K kingae) are also increasing in prevalence.5

History

According to a review of more than 12,000 patients diagnosed with osteomyelitis, the most common symptoms are pain (81.1%), fever (61.7%), decreased range of motion or pseudoparalysis (50.3%), decreased weight bearing (49.3%), and localized symptoms (70.0%).14 Infants and very young children may only present with increased irritability, refusal to use a limb, or poor feeding.12,[15] Relevant history includes recent trauma, recent illness, travel history, animal bites, behavior changes (especially in young children), immunization status, and history of chronic illness.1,11,12

Fever is absent almost 40% of the time, possibly due to use of antipyretics for pain.14 While the classic triad of symptoms is fever, pain, and impaired mobility, the lack of fever does not exclude the diagnosis.

Physical Exam

Similar to presenting symptoms, physical exam findings are often nonspecific. Fever, warmth, and erythema may or may not be present depending on location of infection and causative agent. Pain out of proportion to exam should raise the index of suspicion for osteomyelitis vs cellulitis in the setting of erythema of overlying skin.4 Functional limitations—including decreased range of motion, limp, refusal to bear weight, or pseudoparalysis—are present in 78.2% of patients who present to the ED and are definitively diagnosed with acute osteomyelitis.6 Other findings include focal tenderness (73.5%), swelling (52.1%), and erythema (35.5%).6 Additionally, only 55% of patients may have a fever at any point during their ED visit.6

MRSA is also more likely to result in abscess formation and the need for surgical intervention. MRSA should be considered when more severe symptoms are present (eg, high fever and tachycardia).[16]

Testing

Initial diagnostic testing in osteomyelitis includes x-ray, CBC, CRP, ESR, and blood cultures.5,11 Advanced imaging may be indicated based on patient presentation and test results.

There is no definitive blood test for osteomyelitis. Less than 35% of patients with osteomyelitis will have elevation in the white blood cell count (WBC).14 Blood cultures identify an organism in 10-50% of cases and should be collected before the initiation of any antibiotics. Clinicians should also consider utilizing PCR in patients under the age of 4 as they are susceptible to K kingae.2,[17] This pathogen is difficult to culture because it is slow growing. CRP and ESR are the only labs that are usually elevated, but both are nonspecific.4

CRP is elevated earliest in infection and is indicated by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) for use in diagnosis.4 While some groups have tried to create cutoffs for CRP significance in acute osteomyelitis, there is no consensus as to the importance of the actual level. CRP levels are also utilized to track response to treatment and may be used as a marker to transition from intravenous to oral antibiotics.[18]

In a 2010 publication, 94% of patients diagnosed with either septic arthritis or acute osteomyelitis had an elevated ESR.18 ESR takes longer to normalize than CRP, therefore it cannot be used to track improvement following treatment.18 While CRP was elevated in 95% of patients in the referenced study, the combination of elevated CRP and ESR increased the sensitivity in bacterial osteoarticular infections to 98%.18 The IDSA suggests only using CRP as it has similar sensitivity to ESR and can be used to track improvement, however, the authors of this study still support ESR as part of the initial evaluation.4,18

Imaging

Plain radiograph sensitivity is 16-20%, but radiographs are still useful in initial evaluation of limb pain in children.14,[19] X-ray is inexpensive, widely accessible, and can be used to identify other causes of pain including fractures or tumors.14 Normal x-rays on initial presentation do not exclude the diagnosis of acute osteomyelitis, but they are more likely to be abnormal with prolonged illness when bony destruction would be more visible.13,19 Approximately 30-50% of bone mineralization needs to be compromised before changes are visible on plain radiographs.[20]

Ultrasound has a 17-55% sensitivity in diagnosis of acute osteomyelitis.17,19 It cannot penetrate the bone cortex, therefore, its usefulness in definitive diagnosis of osteomyelitis is limited.20 However, it can help evaluate for fluid collection, subperiosteal abscess, or joint involvement, and guide aspiration for treatment.12 In a recent study of patients diagnosed with osteomyelitis, ultrasound was abnormal in 37% of cases but was diagnostic in only 3.5% of cases.6

Computed tomography (CT) has limited utility in acute osteomyelitis because of radiation exposure and a 1-2 week delay in bone changes visible on exam.20 Sensitivity of 67% has been reported when the imaging was performed on day 10 of symptoms.19

MRI is the modality of choice for diagnosis of acute osteomyelitis with a sensitivity between 80-100%.14,19 It has limitations including cost, availability, time constraints, and the need for sedation in young children. MRI identifies osseous involvement, surrounding soft tissue infection, and septic arthritis and helps to distinguish between noninfectious causes of clinical symptoms.[21] MRI also identifies patients with indications for surgery or invasive procedures. This is important in the setting of more aggressive MSSA and MRSA infections.10

There is no single accurate marker for diagnosis of osteomyelitis. Diagnosis is typically a combination of clinical findings, laboratory results, and advanced imaging. Two studies suggest the following algorithm: clinical presentations of fever (either documented at presentation to ED or measured at home), joint pain, and limited weight bearing with elevated ESR and CRP should have an MRI on initial presentation.7,[22] In a study of 100 children meeting these criteria who underwent MRI, 64% were diagnosed with an infectious cause for their symptoms including osteomyelitis and septic arthritis.22

Management

The treatment of osteomyelitis is antibiotics. Broad spectrum IV antibiotics are often initiated while awaiting the results of blood or tissue cultures following surgery. Antibiotic therapy is then tailored to the identified organism (cultures or PCR) or patient response to treatment. In the past, empiric treatment was a first-generation cephalosporin, however, with the increasing prevalence of MRSA, vancomycin or clindamycin are used more frequently.11 Local MRSA patterns should be considered when making initial antibiotic selection.

Patients not vaccinated for Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB) or those at risk of K kingae should be empirically covered with a first-generation cephalosporin.11

A short course of IV antibiotics followed by initiation of oral antibiotics is typical, however, there is still a lack of consensus on how long oral antibiotics should be continued.11

Surgery is indicated when an abscess or joint involvement is identified on advanced imaging, with less than 10% of patients requiring surgery.14 MRSA infections are high risk for surgical intervention.10,16 Reasons for invasive intervention include pathogen identification, source control, and preservation of function of limb or joint.11 In addition, rapidly progressing infection and sepsis are also indications for more invasive treatment.4 In cases where surgery is not part of the initial management, CRP should be used to monitor response to antibiotic therapy. If there is not rapid improvement in CRP levels (within 48 hours), the option of surgical intervention should be revisited.11

Conclusion

This case shows the insidious nature of a complicated diagnosis in the setting of non-specific pediatric musculoskeletal pain. Common findings in osteomyelitis include fever, pain, skin changes, and functional limitation. Our patient was afebrile throughout the course of his illness, and skin changes did not present until day 5. With the exception of a mild CRP elevation on day 5, labs and x-rays were negative, and multiple visits across specialties were inconclusive. The important finding in this case was the worsening pain that developed over the course of the illness to the point of inability to bear weight along with lack of response to conservative treatment. Fortunately, his infection was treated with a positive outcome and no long-term sequelae. This case serves as an important reminder to consider a broad differential when evaluating musculoskeletal pain in the pediatric population, especially if the symptoms are not responding to conservative treatment. It also highlights the vague presentation of osteomyelitis, which has potential for long-term complications.

Ethics Statement

Patient’s mother provided written consent for publication of this case.

Takeaway Points

- Acute osteomyelitis frequently presents with fever, joint pain, and limited weight bearing.

- Patients with the above triad of symptoms should be transferred to the ED for further work-up.

- Hematogenous spread from transient bacteremia is the most common cause of acute osteomyelitis in children.

- MSSA is the most common pathogen, however an increase in osteomyelitis caused by MRSA is leading to more complicated and virulent infections.

- With a high suspicion for acute osteomyelitis, collect blood cultures and then initiate empiric antibiotics based on local MRSA trends.

Article submitted July 4, 2025; accepted December 19, 2025.

References

- [1]. Thakolkaran N, Shetty AK. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children. Ochsner J. 2019;19(2):116-122. doi:10.31486/toj.18.0138

- [2]. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ Jr. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(13):2279-2284. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01537

- [3]. Arkader A, Brusalis C, Warner W, Conway J, Noonan K. Update in Pediatric Musculoskeletal Infections: When It Is, When It Isn’t, and What to Do. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2016; 24(9):e112-e121.doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00714.

- [4]. Woods CR, Bradley JS, Chatterjee A, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2021 Guideline on Diagnosis and Management of Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis in Pediatrics. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(8):801-844. doi:10.1093/jpids/piab027

- [5]. Gornitzky AL, Kim AE, O’Donnell JM, Swarup I. Diagnosis and Management of Osteomyelitis in Children: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2020;8(6):e1900202. doi:10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00202

- [6]. Stephan AM, Faino A, Caglar D, Klein EJ. Clinical Presentation of Acute Osteomyelitis in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(1):e209-e213. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000002217

- [7]. Vardiabasis NV, Schlechter JA. Definitive Diagnosis of Children Presenting to A Pediatric Emergency Department With Fever and Extremity Pain. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(3):306-312. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.05.030

- [8]. Von Heideken J, Bennet R, Eriksson M, Hertting O. A 10-year retrospective survey of acute childhood osteomyelitis in Stockholm, Sweden. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56(12):1912-1917. doi:10.1111/jpc.15077

- [9]. McNeil JC, Vallejo JG, Kok EY, Sommer LM, Hultén KG, Kaplan SL. Clinical and Microbiologic Variables Predictive of Orthopedic Complications Following Staphylococcus aureus Acute Hematogenous Osteoarticular Infections in Children. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(11):1955-1961. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz109

- [10]. Gafur OA, Copley LA, Hollmig ST, Browne RH, Thornton LA, Crawford SE. The impact of the current epidemiology of pediatric musculoskeletal infection on evaluation and treatment guidelines. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(7):777-785. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e318186eb4b

- [11]. Arnold JC, Bradley JS. Osteoarticular Infections in Children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(3):557-574. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.05.012

- [12]. Yeo A, Ramachandran M. Acute haematogenous osteomyelitis in children. BMJ. 2014;348:g66. Published 2014 Jan 20. doi:10.1136/bmj.g66

- [13]. Van Schuppen J, van Doorn MM, van Rijn RR. Childhood osteomyelitis: imaging characteristics. Insights Imaging. 2012;3(5):519-533. doi:10.1007/s13244-012-0186-8

- [14]. Dartnell J, Ramachandran M, Katchburian M. Haematogenous acute and subacute paediatric osteomyelitis: a systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):584-595. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28523

- [15]. Karmazyn B. Imaging approach to acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children: an update. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2010;31(2):100-106. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2009.12.002

- [16]. Wen Y, Wang C, Jia H, Liu T, Yu J, Zhang M. Comparison of diagnosis and treatment of MSSA and MRSA osteomyelitis in children: a case-control study of 64 patients. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):197. Published 2023 Mar 13. doi:10.1186/s13018-023-03670-3

- [17]. Ferroni A, Al Khoury H, Dana C, et al. Prospective survey of acute osteoarticular infections in a French paediatric orthopedic surgery unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(9):822-828. doi:10.1111/clm.12031

- [18]. Pääkkönen M, Kallio MJ, Kallio PE, Peltola H. Sensitivity of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in childhood bone and joint infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):861-866. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0936-1

- [19]. Malcius D, Jonkus M, Kuprionis G, et al. The accuracy of different imaging techniques in diagnosis of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2009;45(8):624-631.

- [20]. Pineda C, Espinosa R, Pena A. Radiographic imaging in osteomyelitis: the role of plain radiography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and scintigraphy. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23(2):80-89. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1214160

- [21]. Guillerman RP. Osteomyelitis and beyond. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 Suppl 1:S193-S203. doi:10.1007/s00247-012-2594-9

- [22]. Mitchell PD, Viswanath A, Obi N, Littlewood A, Latimer M. A prospective study of screening for musculoskeletal pathology in the child with a limp or pseudoparalysis using erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and MRI. J Child Orthop. 2018;12(4):398-405. doi:10.1302/1863-2548.12.180004

Author Affiliation: Erin Loo, PA-C, MHA, Integrity Urgent Care in College Station, Texas; College of Urgent Care Medicine. Author has no relevant financial relationships with any ineligible companies.