Physical Examination

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs are as follows:

- Temperature: 101.2°F (38.4°C)

- Pulse: 108 beats/min

- Respiration: 20 breaths/min

- Blood pressure: 146/92 mm Hg

The patient is alert and oriented, is not in acute distress, and is breathing comfortably but slightly faster than normal. Examination reveals crackles in the right lower lung field but no wheezing. Her heart rate and rhythm are regular, without murmur, rub, or gallop. Her abdomen has a normal appearance and is soft and nontender without rigidity, rebound, or guarding. She has no swelling or pain in her extremities.

Differential Diagnosis

- Pleural effusion

- Hemothorax

- Lung cancer

- Cardiac tamponade

- Pulmonary embolism

Urgent Care Work-Up

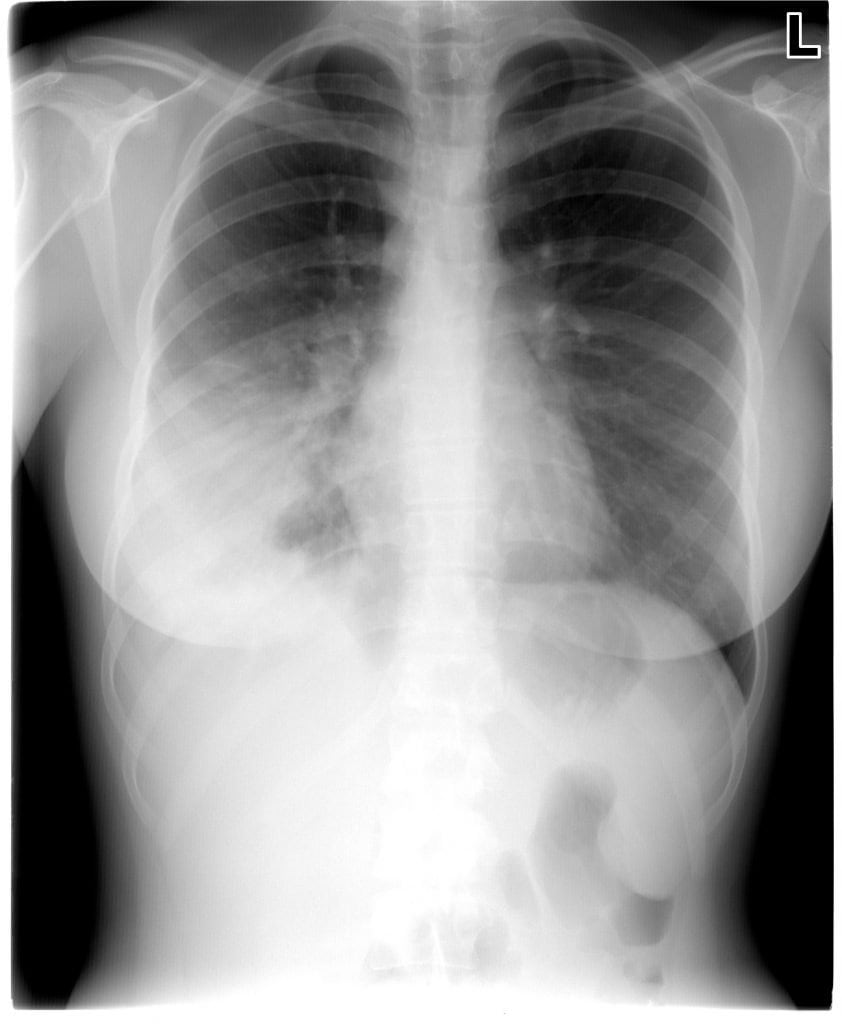

A chest x-ray is obtained, and it shows an infiltrate in the right lower lung (Figure 2).

Diagnosis

Right lower lobe infiltrate.

Learnings

There are up to 4.5 million ambulatory visits per year in the United States, and as many as 1.1 million hospitalizations per year, accounting for 2.2% of emergency department (ED) visits. The annual incidence of pneumonia in patients older than 65 years is approximately 1%. The combination of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and influenza ranks as the sixth leading cause of death in the nation. Mortality for the disease has remained fairly consistent since the 1990s, despite advances in antibiotics and critical-care medicine. Mortality in outpatients is less than 1%.

Pneumonia is an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma associated with symptoms of acute infection and with physical examination and clinical findings consistent with pneumonia and/or the presence of an acute infiltrate on chest x-rays. Pneumonia is considered nosocomial (that is, not community-acquired) if the patient has been hospitalized or treated in an extended-care facility for 14 days before presentation of the current illness.

The most common causes of CAP are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Less common causes include gram-negative bacilli, viruses, Legionella pneumoniae, and Chlamydia pneumoniae.

Obtaining a thorough medical history includes inquiring for symptoms of fever, chills, cough, shortness of breath, myalgias, chest pain (which may be pleuritic), and fatigue. Patients at high risk of poor outcomes include elderly patients, smokers, patients with immunocompromise, and those with a history of a recent influenza-like illness. Risk factors for aspiration include patients who use alcohol, sedatives, or intravenous drugs (decreased level of consciousness while inebriated may result in aspiration or decreased ability to clear secretions), and debilitated patients such as those with cerebral palsy (the recumbent position decreases ability to clear secretions). It is important to inquire as to recent hospitalizations or exposures to ill persons and as to immunization status (influenza and pneumococcal disease).

Conducting a physical examination includes checking for signs of fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxia. Assess the state of hydration, indicated by such conditions as poor skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, and lack of urine output; in some patients, such issues may tip the scales toward hospital admission rather than outpatient therapy.

Findings on the lung examination may be normal or may instead include rales (crackles), rhonchi, bronchial breath sounds, whispered pectoriloquy (the examiner can hear the patient whispering when auscultating over an area of lung consolidation), or egophony (when the examiner is auscultating over an area of lung consolidation, the sound of a spoken vowel is changed—for example, the eee sound is changed from a long e to a short e).

What to Look For

Testing may be deferred with typical cases (a chest x-ray is not always necessary), but with more serious cases, the plain posteroanterior and left lateral chest x-ray is the place to start. Classic findings are a lobar infiltrate (as in Figure 2), most commonly associated with S. pneumoniae. Atypical appearances of pneumonia seen on chest x-ray include the following:

- Pleural effusion

- Parapneumonic effusions (loculated effusion)

- Necrotizing pneumonia

- Nodular or reticular infiltrates; these may be see with Mycoplasma or Chlamydia atypical organisms

- Cavity with air-fluid level: anaerobic lung abscess

- Upper-lobe cavitary lesion: Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Diffuse bilateral infiltrates: Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly known as Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia, viral

Pulse oximetry should be checked with a diagnosis of pneumonia or suspected hypoxemia, but laboratory tests, including complete blood cell counts, arterial blood gas tests, cultures of the blood and sputum, and urine antigen tests, are not recommended in routine cases.

Indications for transfer to an ED include the following:

- Respiratory distress

- Tachypnea

- Retractions

- Associated diaphoresis

- Drooling or stridor

- Altered level of consciousness

- Oxygen saturation of <90%

- Concern that there is a pathogen present with increased virulence, such as methicillin-resistant aureus

- Concern about the patient’s compliance or inability to ensure good care at home

- Toxic appearance of the patient or the presence of underlying medical conditions that predispose to complications

- Scoring systems: There are multiple systems, but the CURB-65 criteria are simple to remember. With a score of 0, there is a 0.6% 30-day mortality that rises to 2.6% with one element positive and 6.8% with two elements positive. If one or two of the following conditions are present, consider transferring the patient to an ED for possible admission.

- C: confusion

- U: uremia (a blood urea nitrogen level of >19 mg/dL), which is difficult to ascertain in the urgent care setting)

- R: respiratory rate >30 breaths/min

- B: low blood pressure, with a systolic blood pressure of <90 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≤60 mm Hg>

- Age >65 years

The decision to use antibiotic therapy should be based on the patient’s age and severity of illness, and on the local resistance patterns of pathogens. In previously healthy patients, starting with a macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone is a reasonable option. Beware of the presence of comorbidities such as these:

- Chronic diseases of the following organs:

- Heart

- Lungs

- Liver

- Kidneys

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Alcoholism

- Malignancies

- Asplenia

- Immunosuppressing conditions or use of immunosuppressing drugs

- Use of antimicrobials within the previous 3 months (in which case an alternative from a different class should be selected)

Follow-up care should be given in 72 hours to determine the response to therapy and to ensure that symptoms are not progressing.