Published on

Urgent message: The urgent care clinic is a prime target for prescription drug abusers seeking possibly inappropriate prescriptions. Clinicians must be vigilant to screen, intervene, and refer such patients.

Marcelina Behnam, MD and Mark Rogers, MD

Over the past several years, prescription drug abuse has become a problem of epidemic proportions for urgent care centers and emergency departments around the country. There has been an increase both in visits related to the acquisition of these medications, and in emergency department visits related to the misuse of prescription drugs.1,2

In response to this epidemic, new government legislation has been enacted and intervention and treatment centers developed. This review article discusses the current problems of prescription drug abuse and substance use disorders (SUDs), as well as measures being implemented to address them.

Rise of Prescription Drug Abuse

Within the past decade, there has been a substantial rise in prescription drug use and abuse.

Drugs of abuse are classified both by abuse potential and pharmacologic action, the latter of which is brokendown into three main categories: stimulants, opioids, and CNS depressants. Each of these categories has seen a rise in use and abuse in the past several years, with opiates being the most commonly abused.1

According to a 2004 national survey on drug use and health published by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 19.1 million Americans were current illicit drug users. Among those 19.1 million, the largest segment (2.4 million) was populated with those engaging in nonmedical (i.e., recreational) use of prescription pain relievers.

In 2005, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 6.4 million Americans over the age of 12 reported using a prescription drug for a non-medical purpose within the past month. Of those:

- 7 million used narcotic pain relievers

- 8 million used tranquilizers

- 1 million used stimulants (including methamphetamine)

- 272,000 used 2

Opiate abuse accounts for more than 50% of prescription drug abuse. Between 2004 and 2005, the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) reported that emergency department visits involving non-medical use for opiate pain meds increased 24% overall.2

The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) diversion drug trend report identified hydrocodone as the most commonly diverted and abused controlled substance in the United States.

Hydrocodone is also one of the most commonly used drugs in the U.S., period. In 2004, this country used 99% of the global hydrocodone supply.1 In 2005, hydrocodone outpaced Lipitor to be the most-prescribed drug here.1,2

Compounding the situation, there has been an in- crease in deaths and ED visits related to misuse and abuse of opiates. Opioid related deaths increased 91% between 1999 and 2002, and by the end of 2002 opioid related deaths outnumbered deaths related to heroin or cocaine.3 In 2004, according to DAWN, there were 1.3 million ED visits related to opioid misuse and abuse. It all added up an estimated $181 billion in healthcare and social costs.1

Why EDs and Urgent Care?

Lack of patient-provider continuity makes it relatively easy for drug seekers to obtain prescriptions; hence, abuse of prescription drugs tends to be more prevalent in the emergency and urgent care settings. In fact, prescription drugs are relatively easy to abuse in most practice settings for a variety of fairly logical reasons. Among them:

- Prescription drugs are perceived to be more socially acceptable and easy to obtain than other illicit drugs like heroin or

- There is good quality control in their

- They are often paid for by insurance companies and are sold on the

There may also be a mistaken impression among the general public that prescription drugs are less dangerous than other drugs of abuse; in 2005, the NSDUH showed that 60% of prescription drugs were given to the user by a friend or relative for free.2 And in June 2006 the national Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) report found 185 Internet sites selling prescription drugs, 89% of which did not require a prescription.2 Other factors that may contribute to the rise of prescription drug abuse include the perception by both physicians and patients that pain is under- treated. Patient advocates have voiced concerns that the war on drugs has made physicians afraid to treat pain.4 Paradoxically, this may facilitate drug seekers playing on a physician’s sympathies to get prescriptions for pain medications.

Striking a balance between good pain treatment and facilitating SUDs is difficult. The Joint Commission’s regulations mandate the monitoring and relief of pain. Physicians are challenged with demands for pain control and the feasibility of chronic pain management.3 Overall, the ready availability of prescription drugs in the U.S. has led to increased popularity compared with their illegal counterparts. Abusers of prescription drugs have developed various modes of diversion through which to obtain medications. Doctor shopping, Inter- net sales, theft, improper prescribing on the part of the physician, and sharing among family and friends are some of the most-often cited.3

Characteristics of a Drug-seeking Patient

Familiarity with some of the characteristics common among drug-seeking patients is particularly important in urgent care and other acute-care settings, where clinicians often encounter patients with whom they have no previous experience.

For example, drug-seeking patients:

- are often described as exhibiting “coercive behavior” and may request a specific drug for their pain, with some experts believing that coercive behavior may be pathognomonic of drug-seeking patients

- are often noted to have escalating use of the drug

- often report that they “lost” their prescriptions

- may partake in “doctor shopping”

- may report multiple drug allergies, especially to analgesics with low abuse

A call to the patient’s primary care physician’s office may reveal multiple missed appointments, more reports of lost prescriptions, and deceptive behavior. However, drug-seeking patients are often reluctant to identify a primary care physician or may claim that their physician is out of town.

Such patients may also falsify symptoms, as well as medical examination tests, in order to deceive providers.5

One example is a patient who was known to repeatedly visit the emergency department with complaints of kidney stones, and who had a history of particularly manipulative behavior. Despite multiple negative CT scans, this patient often received narcotics based on complaints of flank pain and hematuria that latter of which, as eventually witnessed by a nurse, was manufactured by the patient pricking his finger in order to contaminate the urine sample.

Drug-seeking patients are likely to have a history of substance or alcohol abuse. Look for cutaneous signs of drug abuse, such as needle tracks. They are also more likely to suffer from mood disorders. A 2005 study looked at characteristics of drug-seeking patients and found that opioid abusers were characteristically more likely to be young men who have a past history of alcohol abuse, cocaine abuse, or have a previous drug or DUI conviction.6

Approach to the Drug-seeking Patient

Assessment of drug addiction/abuse

It is important to evaluate the patient on a clinical basis and not to dismiss complaints of pain out of hand. Key steps in this evaluation include establishing the initial diagnosis, the medical necessity for pain medication, and weighing the risk-benefit ratio of prescribing pain medications in the evaluation of a suspected drug abuser.3

Patients should be evaluated for signs and symptoms of drug abuse and withdrawal. A discussion with patients regarding past or present alcohol and recreational drug use should always take place whenever one considers prescribing a potentially addictive medication.

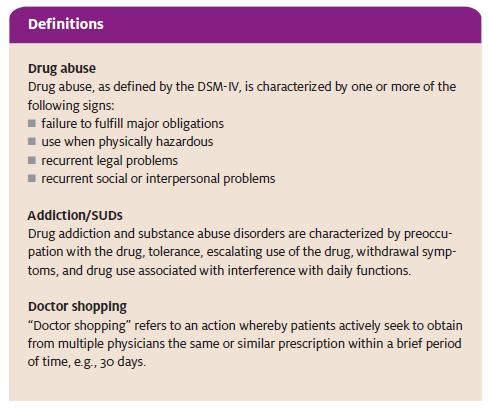

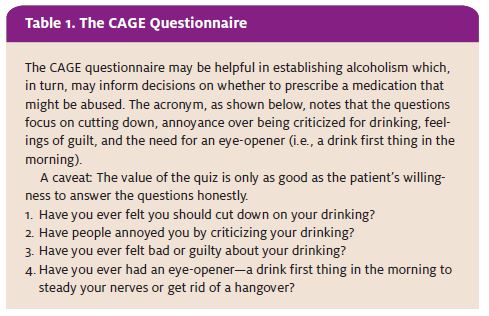

The CAGE questionnaire (Table 1) is useful for deter- mining alcohol abuse and SUDs, which is a useful predictor for prescription drug abuse. It can also be modified to query patients about prescription drug addiction and abuse.

Other surveys have been devised, such as the prescription drug use questionnaire, which consists of 39 items evaluating five different domains. This tool is helpful in identifying addiction risk.5,7 One major limitation to extensive questionnaire use is the feasibility in an urgent care setting. Other modes of evaluating for SUDs and abuse of prescription drugs include a review of the patient’s chart and, in certain states, a prescription monitoring program.

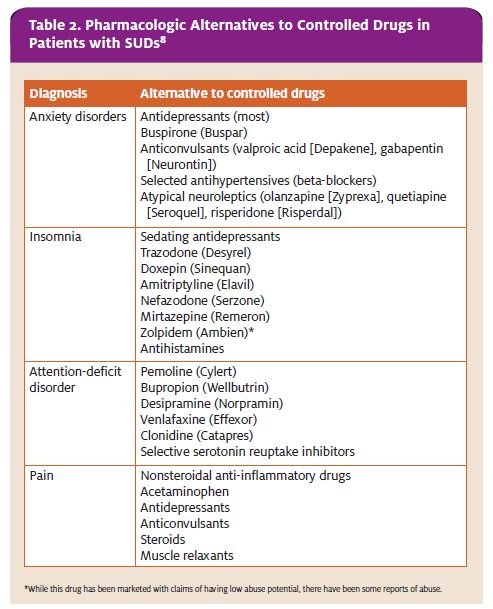

Alternatives to drugs of abuse

If SUDs or recreational use of prescription drugs is suspected with a particular patient but you still feel that patient has a legitimate need, consider prescribing something other than a medication that could be abused by the patient (Table 2).

Drugs with partial opiate receptor activity such as tramadol, for example, have become a popular alternative

to opiate analgesics. These agents are commonly be- lieved to be non-addictive and are often prescribed to ad- diction-prone patients, though there have been multiple reports of addiction to these substances, as well, with an increased prevalence in their abuse. A 2004 survey by the NSDUH found that 1.3 million Americans used tramadol for non-medical purposes. The DAWN 2004 study cited 2,984 ED visits related to tramadol overdose.1 When prescribing these medications, consider the possibility for abuse in those patients with a history of SUDs or drug abuse.

Strategies for dealing with difficult patients

Practice caution when dealing with coercive patients. Avoid feeling compelled to oblige the patient’s requests. If discussion of treatment options escalates to a confrontation with a patient who is requesting a controlled substance, try to do the following:

- Remain calm

- Explain to the patient that what he or she requested is not an option

- Say no

- Offer the patient an alternative

- Demonstrate genuine concern for the patient’s distress, and avoid raising your Also, try to avoid using judgmental phrases or tones.

- Create room for discussion by showing concern and interest for the patient’s well being

Documentation

From a medical/legal standpoint, it is important to document these discussions with the patient in the patient chart.5 In addition, if you suspect that the patient has exhibited repetitive drug-seeking behavior, doctor shopping, or other modes of diversion, make notes of this in the patient’s chart.

This should be done with caution, however, to avoid “labeling” the patient and causing undue harm and bias between the patient and future providers. For this reason, objective language should be used with specific situational references.

Cite in a patient note the nature of the visit, the past prescriptions obtained, what the interaction with the patient was, and an objective description of the patient’s behaviors. It is also important to cite what alternative treatments have been offered to the patient.

Treatment

Finally, if feasible and deemed appropriate in your opinion, direct the patient toward resources to aid in treatment. Current treatment for SUDs is multifaceted. Medical therapy usually involves a combination of pharmaceuticals aimed at reducing the side effects of opiate withdrawal (e.g., clonidine [Catapres], loperamide [Imodium]) and others reducing the craving for the drug itself (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine hydrochloride/naloxone hydrochloride [Suboxone].

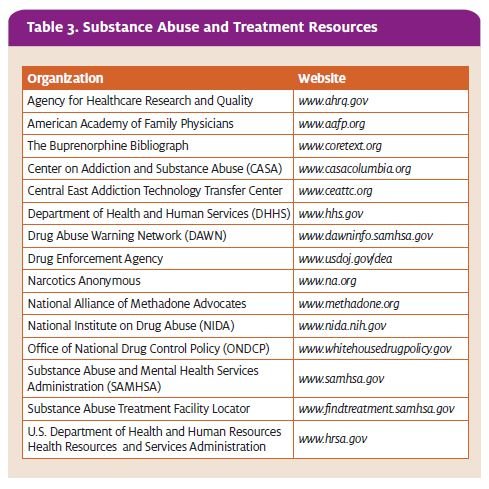

There are a variety of resources available for treatment (Table 3). For example, SAMHSA offers an online Sub- stance Abuse Treatment Facility Locator covering more than 12,000 treatment centers.9 Other resources include the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

Preventive Strategies

Prevention of prescription drug abuse is a multidisciplinary task which involves both public and physician awareness. Education through the media, government agencies, and local campaigns combine to raise public awareness of prescription drug abuse.

As clinicians who are likely to see our fair share of drug seeking patients, urgent care practitioners are in a good position to contribute to public awareness by educating patients and patients’ families on the dangers of addiction and the potential for overdose of controlled substances.

Awareness of which drugs are most likely to be abused helps to facilitate education.

Medications with high potential for abuse tend to have several properties in common, notably:

- rapid onset

- high potency

- brief duration

The formulation of the substance also affects its abuse potential. Water-soluble medications are prone to intravenous use; volatile substances may be smoked. Also, some controlled substances that are manufactured for a slow, time-release delivery may be tampered with (e.g., crushed) so that the entire amount of the active ingredient is absorbed immediately upon ingestion.

- records from the patient’s previous physician before prescribing controlled drugs on a long-term Educational seminars and training designed to in- crease awareness among physicians and patients is needed. ONDCP, NIDA, DEA, SAMHSA, and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) all offer education on prescription drug abuse.

Institutional Policies

In many instances, institutional policies are over shadowed by state and national regulations. In some institutions, hospital committees can help to identify drug-seeking patients and assign these patients to a primary provider.

Other institutions have developed “patient alert lists.” A community-wide system in Calgary, Canada encompasses a group of local hospitals toward this end. Such institutional surveillance may not be feasible in the U.S. due to HIPAA and other federal regulations, however. Private insurers and Medicaid have adopted policies to combat prescription drug diversion, as well.

Prescription monitoring programs

On both state and federal levels, there are programs which monitor the distribution of prescription drugs.

The Kentucky All Schedule Prescrip- tion Electronic Reporting (KASPER) sys- tem, developed in 1998, archives rele- vant information into a database that can be accessed in real time by practi- tioners. The limitations to this system are that drug-seeking patients can go to bordering states that do not use a pre- scription monitoring system.

In an attempt to remedy this problem, in 2003 the Department of Justice initiated the Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, sponsored by the DEA and Congressman

Harold Rogers (R-KY). This initiative was aimed at improving prescription drug monitoring programs among individual states.

Two years later, the National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting Act (NASPER) passed, continuing the funding of state monitoring programs and authorizing spending to improve the communication between the different state programs. While funding has been an issue for these projects, as of 2006 there were 27 states with prescription drug monitoring programs, of which 18 monitored schedule IV drugs and 20 monitored schedule III drugs.2

Prescription drug monitoring programs are a benefit in the states that have these programs. However, at this time there is little communication between neighboring states, and work still needs to be done to make this a national system.

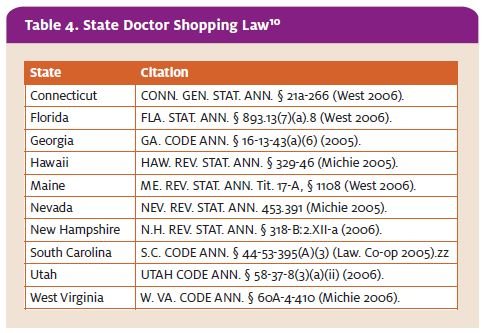

Doctor shopping laws

The National Alliance of Model State Drug Laws is a re- source for legislators and other professionals to help develop laws with the intent to address alcohol and drug abuse. Specifically, they cite the number of individual

Prescriber responsibility and training

There is also concern that the abuse of prescription drugs is due to over prescribing on the part of the prescriber. This may be due, in part, to the fact that many clinicians lack education and training on drug-seeking patients. They may not know how to identify drug- seeking behaviors, or they may be unaware of the signs and symptoms of SUDs. They also may not have strategies to deal with coercive patients, which may lead to trouble saying “no” to patients.3

Research indicates that, as a whole, physicians lack education on prescription drug abuse. For example:2

- Only 19% of physicians report receiving training in prescription drug

- An underwhelming 40% had any previous medical school training in identifying prescription drug abuse and states with doctor shopping laws.

As of 2006, only 10 states had specific laws against doctor shopping (Table 4).

Treatment legislation

Congress passed the Federal Controlled Substance Act, the government’s initial response to the abuse of prescription medications, in 1970. This act classifies drugs of abuse and provides criminal statutes for inappropriate use of controlled substances.

Under the Federal Controlled Substance Act, it is illegal for physicians to prescribe controlled substances to individuals who are known to have an abuse or addiction problem including those for the treatment of withdrawal symptoms.

The Drug Addiction and Treatment Act of 2000 addressed the issue of treatment of individuals who are addicted to controlled substances. Currently, buprenorphine HCl (Subutex) and buprenorphine HCl/naloxone HCl (Suboxone) are the only Schedule III, Schedule IV, or Schedule V drugs with FDA approval to treat individuals who are addicted to con- trolled substances with opiates, or agents with partial opiate receptor activity. This treatment is facilitated through specialty clinics.

Summary

With the implementation of strategies aimed at reducing the diversion of controlled substances, the abuse of prescriptions drugs can decrease. One study identified frequent users in an emergency department, denied them

narcotic prescriptions, provided supportive and addiction counseling, and limited them to one pharmacy. This resulted in a 72% decrease in the use of the emergency department by these frequent users without increased use of other hospitals.4

Prescription drug abuse has grown to epidemic proportions in the past 10 years. One of the challenges in the identification and prevention of prescription drug abuse is the fear of inadequately treating someone’s pain. It is often difficult to discriminate between true disease pathology and drug-seeking behavior.

However, with increased awareness and experience, urgent care providers can help to control prescription drug

abuse by identifying drug-seeking patients through the recognition of their behaviors and diversion techniques. This will allow the provider to treat all patients appropriately and responsibly.

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2005: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. DAWN Series D-29, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 07-4256, Rockville, MD, 2007.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2004: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. DAWN Series D-28, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 06-4143, Rockville, MD, 2006.

- Manchikanti, Prescription drug abuse: What is being done to address this new drug epi- demic? Testimony before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources. Pain Physician. 2006;9(4):287-321.

- From confrontation to collaboration: Collegial accountability and the expanding role of pharmacists in the management of chronic J Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2001; 29:69.

- S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Agency Office of Diversion Control. Don’t Be Scammed by a Drug Abuser. Available at www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/brochures/drugabuser.htm#recognize. Accessed April 4, 2008.

- Ives TJ, Chelminski PR, Hammett-Stabler CA, et Predictors of opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain: A prospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:46.

- Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, et College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: Position statement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69(3):215-232.

- Longo LP, Parran Jr T, Johnson B, et Addiction: Part II. Identification and management of the drug-seeking patient. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:2401-2408.

- Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Substance Abuse Facility Locator. Available t www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov. Accessed April 4, 2008.

- The National Alliance for Model State Drug 700 North Fairfax Street, Suite 550, Alexandria, VA 22314. Phone: (703) 836-6100. Research current through July 21, 2006.

- Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate NIH Consensus Statement 1997. Nov 17-19; 15(6):1-38.

- Manchikanti, National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: Facts and fallacies. Pain Physician. 2007;10(3):399-424.

- Furrow Pain management and provider liability: No more excuses. J Law Med Ethics. 2001;29(1):28.

- Wilsey BL, Fishman SM, Ogden Prescription opioid abuse in the emergency department. J Law Med Ethics. 2005;33(4):770-782

- Wu SM, Compton P, Bolus R, et The addiction behaviors checklist: Validation of a new clinician-based measure of inappropriate opioid use in chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Man- age. 2006;32(4):342-351

Hansen The drug-seeking patient in the emergency room. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):349-365.