Urgent message: While common perceptions are that the plague—the infamous microorganism that claimed the lives of countless millions in ancient times—has been eradicated in modern society, infections still occur, even in the United States. While the odds of encountering a patient infected with the plague are thin, its presentation of flu-like symptoms—which could easily lead a patient to urgent care—make it a diagnosis urgent care providers should be aware of.

Introduction

Yersinia pestis—known commonly as plague, the disease it causes—is one of the most infamous microorganisms in the world. Surprisingly, a common misconception is that plague has been eradicated. Plague is a rodent-carried disease which has generally been considered one of the deadliest illnesses in history. Thankfully, with modern medicine, plague is treatable if caught early; with urgent cares being on the front-lines of treating nonemergent injuries and illness, many urgent care centers could potentially have a plague case walk through their doors.

History of Yersinia pestis

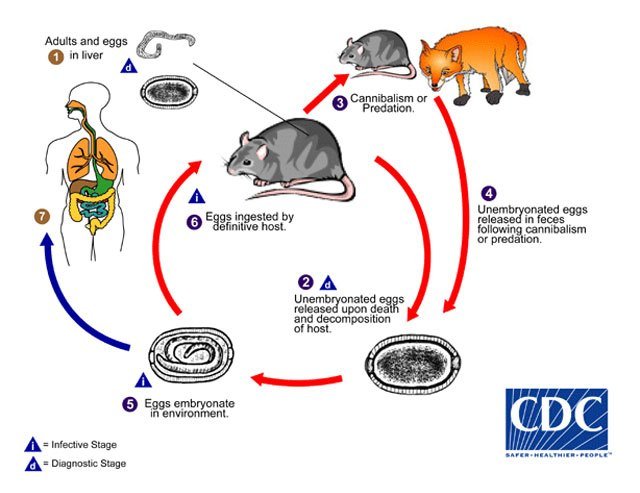

Most commonly known for sweeping through the Old World during the Middle Ages and known as The Black Death, plague is one of the deadliest infections in history.1 The plague was first recorded in the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Justinian I, circa 541 AD. In the 1300s, in China, an outbreak spread across trade routes and decimated an estimated 60% of all European populations.2 More recently, during the tail end of the 1800s, plague was carried by ship routes throughout the world, killing 10 million. The disease is carried by small animals such as rats, mice, and squirrels, and jumps to humans through bites from fleas (Figure 1). The availability of small animal hosts quickly enables the transmission to a host of populations through carrier-mediated transmission.

Plague Types and Symptoms

There are three types of plague:

- Bubonic, characterized by sudden onset of fever headache and chills with tender lymph nodes. Results from the bite of a flea and localized to the nearest lymph nodes. If not treated, can spread to the rest of the body.

- Septicemic, with symptoms that include fever, chills, abdominal pain, shock, and bleeding into skin and organs. Skin and surrounding tissue may become necrotic and turn black. Transmissible from a flea bite or handling infected animals.

- Pneumonic, whose symptoms include fever, chills, weakness, and a rapid onset of pneumonia with secondary symptoms of chest pain, coughing, and bloody mucous. Transmissible through inhaling infectious droplets, or from untreated bubonic or septicemic infections.

Case Distribution Globally

There are roughly 2,000 confirmed cases reported to the WHO yearly; however, many experts believe that estimate is lower than the number of actual cases in the world.3 Plague is endemic to the Western United States, Africa, and Asia, with the majority of cases occurring in South East Africa (Figure 2).

U.S. Cases

There were approximately 1 to 17 cases of plague per year in the United between 2000 and 2015. The majority of these cases were located in the western states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado (Figure 3).3 Eighty percent of cases in the United States are bubonic plague and affect all ages and genders, with 50% of cases occurring from adolescence to middle adulthood (12-45 years old).3 Plague is a reportable disease, and clinicians should notify all necessary authorities once a potential case is suspected.3

Differential Diagnoses

The majority of plague symptoms are similar to those of other common infectious diseases such as influenza and the common cold. To determine the potential of a plague case, be aware of differential diagnoses such as:

- Influenza

- Cellulitis

- Dengue

- Malaria

- Bacterial sepsis, pneumonia, or pharyngitis

- Tonsillitis

The largest determining feature of plague is the presence of buboes, which are swollen, painful lymph nodes commonly seen with the bubonic form of plague.5 Septicemic plague and pneumonic plague do not have any other obvious signs of plague infection and must be tested for. Physicians should also look for inflamed or nearby insect bites which could indicate plague transmission.5

Once a person under investigation (PUI) has been identified, transfer to an appropriate facility should be an immediate priority. To identify an appropriate receiving facility, the urgent care center should contact the local department of public health. If this is not possible, then call the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100. These departments will be able to provide a list of facilities that can isolate and treat a patient with plague and provide the urgent care center with up-to-date guidelines on how to isolate the patient until the transfer is initiated. If your urgent care center is unable to transfer the patient to a receiving facility or if the patient is in unstable condition, obtaining samples in a timely manner is critical due to the severity of the disease. Once samples have been taken, antibiotics started and the patient transferred, the urgent care physician should update the infectious disease specialist who will be continuing ongoing management.

Diagnostic Testing

With an incubation period of 2-6 days, if plague is suspected and transfer of the PUI is unavailable, pretreatment specimens should be taken if possible; regardless, treatment with antibiotics should not be delayed. Specimens should be obtained from the PUI from appropriate cites for isolating the bacteria, and depend on the clinical presentation:

| Table 1. Molecular and Serologic Tests for Plague | ||

| Tests | Samples | Type of plague |

| Culture/microscopy | Lower respiratory tract: sputum, aspirate, and lavage taken from affected bubo or surrounding lymph nodes Sputum taken can be isolated or cultured |

Bubonic Pneumonic |

| Bronchial/tracheal washing: throat specimens are not ideal but could also be cultured | Pneumonic | |

| Smear | Blood smear taken from patient—may be negative by microscopy but positive by culture | All types |

| RT-PCR or DFA | Tissue samples taken postmortem: lymphoid, spleen, lung, and liver tissue or bone marrow | All types |

| RT-PCR = Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. DFA = direct fluorescent antibody |

||

Vaccination and Treatment

Plague vaccines were available, but were decommissioned within the United States. Currently, there are several different kinds of vaccines being developed but none are approved for use in the United States. Plague, however, is easily treatable with modern antibiotic if caught in time. The CDC provides dosage guidelines here.

Conclusions

While the management of a plague case is outside the scope of an urgent care center, facilities and healthcare workers within the endemic areas should be prepared for the diagnosis of a plague patient. These cases may be rare, but they can be fatal if they are not identified quickly and antibiotic administration is delayed. Urgent care centers need to be up to date on current plague cases and outbreaks, as well as current CDC guidelines for plague testing.

Charis Royal, BS holds degrees in biology and anthropology. She is working in healthcare and research while working toward Masters degrees in Biosecurity and Public Health (with an emphasis on infectious diseases) and applying to MD–PhD dual-degree programs.

References

- Rosen W. Justinian’s Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Birth of Europe. New York, NY: Viking; 2007.

- Benedictow OJ. The Black Death, 1346-1353: The Complete History. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer; 2004.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yersinia pestis. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID). Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD). January 2015.

- Kugeler KJ, Staples JE, Hinckley AF, et al. Epidemiology of human plague in the United States, 1900–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(1):16.

- Nikiforov VV, Gao H, Zhou L, Anisimov A. Plague: clinics, diagnosis and treatment. In: Yang R, Anisimov A, eds. Yersinia pestis: Retrospective and Perspective. Houten, The Netherlands: Springer Netherlands; 2016:293-312.