Published on

Charis Royal, BS

Urgent message: With recent outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Ebola, being able to quickly and accurately diagnose such diseases is paramount for initiating containment and treatment procedures in a timely manner.

Introduction

In 2012 a novel coronavirus was discovered in the Arabian Peninsula, with signs and symptoms similar to those of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). This coronavirus was named Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and has infected over 1300 individuals since 2012.1 SARS-CoV infected more than 8000 individuals around the world and caused more than 700 deaths within 8 months. These two viruses exhibit multiple similarities, such as signs and symptoms, routes of transmission, and prevalence of health-care-related infections.

The potential for MERS-CoV to become a pandemic similar to SARS-CoV is a concern for health organizations around the world. The World Health Organization has instigated strict surveillance of countries with confirmed cases of MERS-CoV.2 The key to diagnosing infectious diseases is understanding the susceptible population and being aware of the potential for an outbreak. Novel viruses targeting the respiratory system are difficult to distinguish from other more common viruses, such as those causing influenza or colds, but in-depth questioning of the patient to elicit significant exposure factors such as recent travel or exposure to individuals already infected assists in identifying other patients who may have MERS-CoV. These candidates then must undergo screening for MERS-CoV via molecular and serologic tests.

Condition Overview

MERS-CoV causes respiratory illness and may be compounded by acute pneumonia, septic shock, and multiorgan failure.1,3 Currently, more than 1300 MERS-CoV cases have been confirmed; approximately 35% of patients with the disease die. A disproportionate number of patients are men in late adulthood with chronic comorbidities, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The incubation period for MERS-CoV is roughly 2 to 14 days, with a median of 5 days.3,4 MERS-CoV is transmitted from human to human and spreads rapidly in hospital and clinic settings. MERS-CoV seems to target a specific population, and there are several red flags that providers should keep in mind when assessing a potential MERS-CoV case (Table 1).

| Table 1. Red Flags for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus | |

| Category | Details |

| Symptoms | Fever with

|

| Travel history |

|

| Demographics | Elderly, men, patients with multiple comorbidities |

| Occupation | Health-care workers |

| Contact |

|

| MERS-CoV = Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. | |

Figure 1

Preparation for Clinical Evaluation

Since the beginning of the Ebola epidemic, urgent care providers have prepared to accurately diagnose and treat potential epidemic diseases. It is important to obtain a detailed travel history from the patient and a history of contact with anyone who might have MERS-CoV (Table 2). Be aware of countries where travel could place a patient at risk, and know the proper agencies to which to report a probable case.

| Table 2. Information to Obtain from Patients Who May Have Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus | |||||

| Initial Questions to Ask | Additional Questions to Ask If the Answer Is Yes | ||||

| Have you recently travelled outside the United States? |

|

||||

| Have you been in contact with anyone traveling outside the United States? |

|

||||

| Have you been in contact with any individuals known to be infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus? |

|

||||

Sign and Symptoms Associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

Patients infected with MERS-CoV typically present with signs and symptoms similar to those of influenza.1 Mild symptoms include fever, chills, body aches, sore throat, and runny nose; more severe symptoms include septic shock, pneumonitis, and multiorgan failure.1,4 Because of the impact of the disease on immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, symptoms vary from patient to patient and range from mild to severe (Table 3).

| Table 3. Signs and Symptoms of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus | |||||||||||

| Intensity | Signs and Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Mild |

|

||||||||||

| Have you been in contact with anyone traveling outside the United States? |

|

||||||||||

Laboratory Testing and Treatment Options

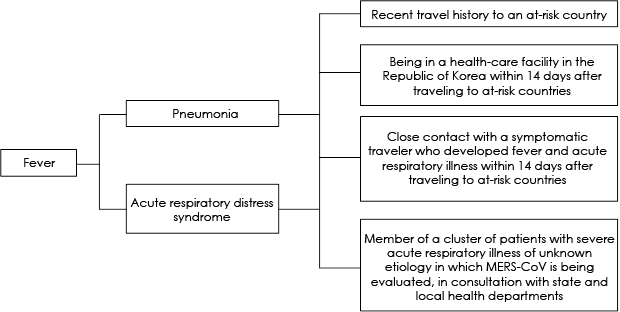

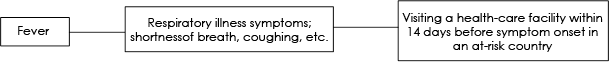

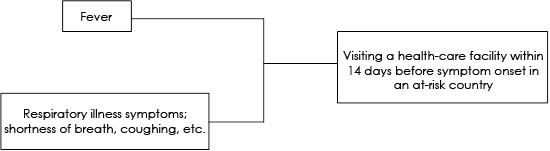

Physicians can use criteria from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to determine whether to test a patient for MERS-CoV. After completing a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s medical history and current symptoms, physicians can choose from three pathways for testing a patient under investigation (PUI) for MERS-CoV2,3 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

A.

B.

C.

Once a PUI has been identified, transfer to an appropriate facility should be an immediate priority. To identify an appropriate receiving facility, the urgent care center should contact the local department of public health. If this is not possible, then call the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100. These departments will be able to provide a list of facilities that can isolate and treat a patient with MERS-CoV and provide the urgent care center with up-to-date guidelines on how to isolate the patient until the transfer is initiated.

If your urgent care center is unable to transfer the patient to a receiving facility or if the patient is in unstable condition, obtaining samples in a timely manner is critical. Several different samples must be collected during evaluation. To determine if a PUI has MERS-CoV, conduct both serologic tests and molecular tests.

Serologic tests identify antibodies to MERS-CoV but should not be used for diagnostic purposes. Patients with positive findings on a serologic test have been exposed to the MERS-CoV but are not actively infected. Molecular tests, on the other hand, use the reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay developed by the CDC to determine if the patient has an active MERS-CoV infection. A PUI with negative findings on one molecular test is considered not to have MERS-CoV. A patient known to have had MERS-CoV must have negative findings on two consecutive tests to be considered cleared of infection. Follow-up tests should be collected every 2 to 4 days until the patient is cleared of infection. Several samples must be taken from PUIs for both molecular and serologic tests2 (Table 4).

| Table 4. Molecular and Serologic Tests for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus | |||

| Type of Case | Tests | Samples | Timing of Samples |

| Symptomatic | RT-PCR | Lower respiratory tract: sputum, aspirate, and lavage | At time of evaluation |

| Upper respiratory tract: nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs, nasopharyngeal wash/nasopharyngeal aspirate | Patient must present samples until 2 successive samples produce negative findings | ||

| Serum for virus detection | |||

| Serology | Serum | Initial sample: the first week of illness | |

| Second sample: 2–3 weeks after initial sample | |||

| Asymptomatic; routine testing not recommended | RT-PCR | Required: nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs | Baseline serum: within 14 days of last documented contact |

| Recommended: sputum | |||

| Serology | Serum | Baseline serum: within 14 days of last documented contact | |

| Convalescent serum: 2–3 weeks after baseline | |||

| RT-PCR = Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. | |||

Currently there is neither a vaccine to prevent infection nor a standard treatment.1,2 Treatment options are limited to those meant to relieve infection symptoms by maintaining organ function, preventing pneumonia, and controlling septic shock. Physicians must report any potential PUIs to local and national health-care agencies. The CDC has an easily accessible online form for doing that: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/data-collection.html.

Preparing an Urgent Care Center for Potential Contact with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

Physicians can prepare their facility for a potential contact with patients who have MERS-CoV in several ways. Preparation includes not only being up to date on protocols and knowledge of current outbreaks but also organizing staff members and health-care workers (HCWs) and alerting patients to the potential presence of MERS-CoV. Here are a few ways to accomplish these goals:

- Workshops for employees to teach proper personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols for samples and contact with patients: One of the critical factors in outbreak containment is the use of PPE and containment protocols. Following the standard PPE protocols used in hospital settings is a good first step in protection against MERS-CoV, but unfortunately information about transmission of this particular disease is limited. Therefore, current understanding of the most recent CDC and World Health Organization guidelines for sample handling should be followed. Holding workshops for your urgent care center, with handouts and discussions of the current guidelines, is an excellent way of making sure your staff members and HCWs can protect both themselves and patients.

- Notices encouraging patients to disclose recent travels: Because of the potential for virus carriers to travel internationally, posting clear notices that urge patients to disclose recent travel is an easy way to initiate a threshold exposure assessment. Seeing small notices around your center can prompt patients who may recently have traveled to an at-risk country to notify staff members or HCWs of their travel history. This precaution can make possible early detection of a MERS-CoV infection and can provide time to isolate the patient and initiate PPE protocols for staff members and HCWs.

- Bulletins to help people understand what to look for: Unfortunately, the average person does not understand the potential for contracting a serious infection just through their activities of daily living. Contact with a friend, coworker, or even someone in line at a coffee shop can be a potential infection point, and more often than not, the individual will assume that their symptoms are a sign of seasonal allergies or a common cold. Urgent care centers can inform the public of signs to look for by posting user-friendly bulletins with easy-to-understand pictograms around the office. These bulletins can go hand-in-hand with the notices about recent travel to help patients understand the significance of their symptoms.

Isolation Procedures and Transfer to Hospitals

The potential for MERS-CoV to become a pandemic is a concern if proper isolation and containment procedures are not initiated quickly. The CDC has implemented a set of guidelines on preparing your facility for a patient with MERS-CoV1:

Respiratory Hygiene

- Ensure that patients, staff members, and HCWs are aware of and understand proper handwashing procedures, cough and sneeze etiquette, and triage procedures.

- Consider placing patients who are exhibiting respiratory infection symptoms in an area away from other patients.

- Quickly identify and triage patients who may have MERS-CoV.

- Post visual aids around the office about good hygiene, such as using proper handwashing procedures, facial masks, and cough and sneeze etiquette.

- Provide patients, staff members, and HCWs with hand sanitizer, face masks, and tissues.

- Immediately isolate PUIs.

Personal Protective Equipment

Staff members and HCWs should be properly trained on isolation procedures and have access to all PPE required by N95 facial respirator standards. The PPE recommended by the CDC include the following:

- Gloves

- Gowns

- Respiratory protection (i.e., N95 facial respirator)

- Eye protection

All staff members and HCWs must wear PPE when in contact with a PUI; all PPE should be replaced or changed after use, in accordance with CDC guidelines.1

Isolation and Transfer

Patients should be isolated in an airborne infection isolation room. If your facility does not have such a room, the patient must be transferred immediately to a facility that does. In the interim, place the patient in an examination room and instruct the patient in how to wear an appropriate respiratory protection mask. To transfer a patient to a receiving facility, contact the nearest emergency department and report that you have a possible MERS-CoV case. After confirming that the receiving facility has appropriate isolation quarters, staff members, and HCWs, inform the patient which hospital he or she will be transferred to.1,2 In preparation for the transfer, be sure to include all clinical findings and evaluations of the patient. Be sure to report which MERS-CoV PUI criteria the patient meets, and ensure that an entire history of the evaluation and isolation procedures is accurately depicted in your report.

Manage Interactions Among Patients, Staff Members, and Health-Care Workers

Once isolated, the patient should have contact with only the absolute minimum medical personnel necessary to provide patient care. If possible, the facility should appoint a dedicated HCW to provide patient care. Facilities should keep track of all personnel who come into contact with a PUI as well as any family member who accompanied the patient to the facility. The urgent care center should immediately cease intake of more patients and reduce interaction between staff members and HCWs caring for the potentially infected patient and other patients within the facility.2

MERS-CoV can easily spread within health-care facilities, so once a PUI has been identified and isolated, be sure to sanitize any area in which the patient was cared for. All HCWs should be monitored for at least 14 days after contact with a PUI. All HCWs who wore PPE should report any symptoms of illness immediately to a supervisor and suspend work activities. Any HCW who treated a patient who was later identified as a PUI should immediately be notified, suspend work activity, and undergo medical evaluation.2 Facilities should provide adequate time and resources for any HCW who has to suspend any work activities because of possible contact with a PUI.

Running an urgent care center requires continual effort to keep practices and services up to date. In the face of a MERS-CoV outbreak, it is paramount that the facility and its staff members and HCWs are prepared to deal safely with patients who may have the disease. Even though current research findings on MERS-CoV are limited, using standard containment protocols, being up to date on CDC guidelines, and enabling public awareness are key in providing the best possible care for patients who may have MERS-CoV.

Charis Royal, BS, is a graduate of Arizona State University, holding two bachelor of science degrees, one in biology and one in anthropology. She has been studying the evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus since it was first reported in 2012. She is currently working in the health-care field and applying to MD–PhD dual-degree programs to continue her studies on the effects of infectious diseases on the human population.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [updated 2015 July 6; accessed 2015 August 8]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/about/index.html

2. World Health Organization. Laboratory testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: interim recommendations (revised). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; © 2015. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/176982/1/WHO_MERS_LAB_15.1_eng.pdf

3. Kapoor M, Pringle K, Kumar A, et al. Clinical and laboratory findings of the first imported case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus to the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1511–1518. Available from: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/59/11/1511.long

4. Guery B, Poissy J, el Mansouf L, et al; MERS-CoV study group. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265–2272. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(13)60982-4/fulltext.