Urgent message: Laceration repair is one of the first skills urgent care clinicians are expected to learn and master. While much research and coursework are devoted to proper technique, very little attention has been paid to the tools of the trade. The author conducted his own research project to understand the essence of the individual instruments and instrument kits in the hope of optimizing (or improving) their design and use.

Patrick O’Malley, MD

INTRODUCTION

Urgent care and emergency clinicians are all too aware that not all laceration kits are created equal. We’ve felt the frustration of having to stop in the middle of a procedure to go open another kit because the scissors won’t cut the suture, or the suture thread gets snagged on the hinge of the needle driver while tying a knot. Other times, everything goes according to plan and the patient (and the provider) are satisfied.

Thinking there must be a better way, I set out on a personal research project—admittedly, not very academic in nature—to try to understand what made some laceration repair kits superior to others. Not being an avid researcher, but rather an experienced physician who developed a wound irrigation device of sufficient quality to have a medical supply company buy it, I knew my efforts would begin with a focus on the instruments themselves.

I learned a few valuable lessons, such as the role economics play in which kits are bought by various institutions and how such decisions affect patient care, clinician preference, and clinical outcomes. These, and the data collected, are discussed in greater detail below. It’s important to note that these are just one clinician’s observations, informed by close but nonscientific research, and not an endorsement or critique of any one product.

GOALS

- For those who are forced to use inferior instruments that break or just don’t work well, to utilize this information and get better laceration kits.

- For administrators, supply chain, and accounting personnel to realize that this is a big deal and we need better instruments. Save money on tongue depressors, not the instruments we use to stitch people back together. The cheapest option may not be the right choice.

- Bring the issue to light and stimulate further research.

BACKGROUND

At the outset, I learned there were 137 million ED visits in 2015. Of those, 4%—over 5 million—involved patients with an open wound.1,2 According to data drawn from JUCM research, lacerations are among the top 10 complaints patients present with in urgent care.3 Needless to say, this is a common reason for which Americans seek treatment in the acute setting.

Getting financial information on the cost of a laceration repair is difficult. The laceration may be very simple, or it may be in the context of a fall in an elderly patient undergoing an extensive workup for other things. The overall bill a patient receives for their isolated laceration repair may be anywhere from several hundred to thousands of dollars. As with many presentations, comparable-sized lacerations repaired in an urgent care will be less expensive than if repaired in the emergency department. In either setting, the cost of a laceration kit, ranging from $5 to $15 each, is a small component of this overall charge.4

While high-quality, reusable surgical instruments can last for decades, they also cost hundreds of dollars and require the use of an autoclave or a sterile processing department. Consequently, single-use laceration repair kits tend to be much more commonly used in acute care settings. The downside to this is that the quality of instruments can vary widely. From this we could draw the conclusion that convenience and cost trump quality.

Another common concern with single-use kits is the environmental impact. Although this concern is not likely to overcome the cost and simplicity of single-use instruments, anything that can be done to minimize the environmental impact of single-use medical equipment is worth consideration.

For the clinician, however, outcomes are likely the most important consideration. And poor outcomes, when it comes to laceration repair, can have longstanding cosmetic and psychosocial ramifications. Unfortunately, anecdotal evidence and years in the trenches reveal that acute care clinicians are often expected to take on this important task with the cheapest laceration kit instruments available.

INSTRUMENTS

The purpose of this paper is to illustrate the roles and importance of the various metal instruments used in laceration repair. It will not focus on the other elements such as drapes, gauze, needles, syringes, and other accompaniments that may or may not come as standard issue in the variety of kits that are commercially available. It will also discuss implications of poor instrument quality, and possible barriers that can be overcome so clinicians in the acute setting can have the tools that they need.

Just to establish a common understanding of the instruments that were considered in the research project, as well as what might make one instrument preferable to another, let’s specify key considerations for various instruments.

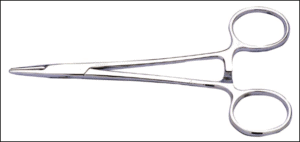

Needle Driver

Needle drivers are a hinged instrument used to grip the suture needle, allowing it to be introduced through the tissue. It must also be able to grab the suture thread in order to tie knots, approximating the tissue. Issues arise when the closed ends are not able to adequately grasp the needle or thread, or when fine suture thread gets caught in the hinges or irregular edges when tying knots. This can lead to unnecessary use of additional suture packs (therefore, more expense).

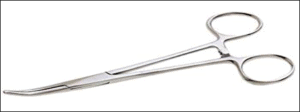

Hemostats

Hemostats are used to clamp off blood vessels, manipulate tissue, and often to break up loculations inside of an abscess cavity. The utility of this device needs further investigation in the actual management of lacerations.

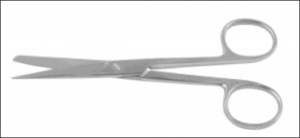

Suture Scissors

Scissors are used to debride tissue, undermine wound edges in some repairs, and to cut suture thread. Poor quality can lead to tissue damage and inability to cut suture material.

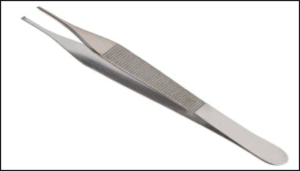

Tissue Forceps

Tissue forceps are tweezer-like instruments used to manipulate tissue. They may have flat, ridged, or sharp teeth-like ends that come into contact with the tissue. They can also be used to grasp and manipulate the needle during a laceration repair. Concern arises with damage to delicate tissue from the teeth and the amount of force required to adequately grasp tissue.

METHODS AND DEMOGRAPHICS

In order to gauge what clinicians think about this issue, a survey was designed using the commercially available survey generation program, Survey Monkey. Twenty-eight questions were generated to cover a variety of topics and get feedback on clinicians’ experience with single-use, disposable instruments. A survey link was generated and distributed on a number of social media groups and via email to contacts the author has relationships with. This was a convenience sampling, but the author was not able to personally identify which respondents gave which answers.

A total of 124 respondents filled out the survey; 66% were physicians, 33% were physician assistants, and fewer than 1% were nurse practitioners. They self-identified as practicing in urgent care, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. Most—89%—are using single-use kits as opposed to autoclaved instruments, 96% are repairing lacerations on a daily or weekly basis, and 75% have been practicing for 6 years or more. As such, we can conclude that these people have significant experience in laceration management and have well-informed opinions in discussing this topic.

THE RESULTS, AND WHAT THEY CAN TELL US

Instrument Failure Is Common

More than three quarters of participants (78.7%) have dealt with instrument failure, with 46% having to open a second kit on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. For the typical clinician, this would of course be considered unacceptable. However, clinicians are not the ones making decisions on what to purchase; rather, such decisions seem to be based too often (or even solely) on price.

What is likely overlooked is the fact that a significant percentage of kits are faulty, and a second or even third kit is being used, thereby increasing the overall expense. Based on what the author was able to determine, the entry level cost of a laceration kit commonly used is around $10. If even 20% of these kits fail, leading to the use of a second one, the effective cost is now $12.

This goes beyond price, however. Patient outcomes, patient and clinician satisfaction, and patient throughput are also negatively affected by these faulty kits.

It is very interesting to note that the needle driver—deemed the most important instrument in laceration repair by 94% of respondents—is the one most likely to fail. This is a significant pain point. (Because the hemostat is the least important instrument, per the survey, it may be questionable as to whether this should be included in standard kits.)

Patient Outcomes

As this was not an outcomes study, this is a subjective question that looks at clinician perception of possible outcomes based on their experience with lower quality instruments. Unfortunately, 68.9% of respondents claim that patient outcomes are affected by instrument use. The question does not specify whether the outcome is a positive or negative one, but one can assume that higher quality instruments would lead to better outcomes and lower quality instruments lead to worse outcomes.

Patient Throughput

Time is of the essence in both the urgent care center and the ED, and anything that impedes flow and slows nurses and physicians down has downstream ramifications. In this survey, 87% of respondents claimed that poor quality kits negatively impact patient throughout. Having to stop what one is doing to go find additional materials adds time to that patient’s visit and prevents the physician from doing other tasks.

The ripple effect of this can be systemic. On a busy day when a physician may have several lacerations to repair, these delays may lead to increased length of stay but also lengthen wait times and, ultimately, move some patients to leave without being seen. This is a revenue loss for that department. Furthermore, this patient may not return to the same facility in the future because of their experience, representing future revenue loss.

Patient and Clinician Satisfaction

We did not investigate the true impact of poor-quality instruments on patient satisfaction, but clinician perception of patient satisfaction is significantly impacted by this issue; 65.9% of respondents claim that patient satisfaction is negatively affected by use of poor-quality instruments.

Patient satisfaction has turned healthcare into “Yelp Care” and healthcare facilities across the board are pumping billions of dollars into patient satisfaction, often holding physicians accountable for things beyond their control. Further, clinician burnout is rife and has been called a crisis. Only recently have hospitals begun administering physician satisfaction surveys, though many clinicians rightfully wonder if this is just window dressing, rather than an effort to assess the need for change. A staggering 93.6% of respondents stated this is an issue for them in their clinical practice, and negatively affects their job satisfaction.

Ask, but Ye May Not Receive

Many clinicians—67%, of respondents—are proactive in asking for better instruments. Only 37% said they were able to get them, however. It is telling that clinicians have such little input and impact on the ability to get the tools that we need to do our job. Maybe this is one of the contributing factors that has led to physician burnout and lack of clinician satisfaction.

Cost and Brands

Estimation of price for a single-use laceration kit is variable, but 51% state that cost is between $6 and $12.99. What clinicians think is a reasonable cost for laceration kits is also variable; 54% feel that paying more than $13 is reasonable. From this, we can surmise that clinicians feel that paying more for quality is warranted. Overwhelmingly, but not surprisingly, 78% of respondents do not know the manufacturer of the kits used at their facility.

SUMMARY

Veteran clinicians have extensive experience managing lacerations in the acute settings. Most repair lacerations on a daily or weekly basis. Needle drivers are felt to be the most important instrument, but the one most likely to fail or cause problems. Instrument failure is common, leading to the opening of extra kits. Inferior quality instruments are felt to contribute to decreased patient throughput, patient satisfaction, clinician satisfaction, and worse patient outcomes. Most physicians have asked for better instruments, but are overwhelmingly told that is not an option, with cost being the main reason. Physicians have little insight into cost of laceration kits, but most believe that paying more for high-quality instruments is warranted.

CONCLUSION

This is something so very simple. If hospitals and urgent care clinics want to have satisfied clinicians and provide the best care possible for their patients, a few extra dollars for functioning laceration instruments would be a good place to start.

A laceration kit is not specifically charged to the patient; it is a bundled charge, so the patient is not seeing the true cost of the actual kit. When an extra kit is opened, the patient is not paying for it, the facility is. Do hospital administrators and purchasing departments keep track of faulty instruments? Likely not, as the clinician will just grab another kit and do the job. No one knows, it just falls off the radar and is not accounted for. It can be assumed that the manufacturer never hears of it and the facility certainly is not being reimbursed for these faulty instruments. The argument of being cheaper will not likely stand up to scrutiny when this is taken into account.

Repairing lacerations is one of the most common procedures done in the settings covered by the survey. Clinicians take pride in being able to perform this basic, yet often complex, and always important task. A few extra dollars to get higher quality instruments is a small price to pay. This is a major pain point for clinicians.

No one would expect a surgeon in the operating room to function with instruments that fail 20% of the time. Why should urgent care centers and emergency departments be expected to settle for this?

It’s important to be fiscally responsible, and it’s everyone’s responsibility to look for areas to cut costs. Cheap laceration kits with inadequate instruments are not the place for this to happen.

(Full results of the survey are available at https://www.surveymonkey.com/results/SM-PCSLXGTBV/.)

Patrick O’Malley, MD is an Emergency Physician at Newberry County Memorial Hospital, Newberry, SC.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2015_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- North Carolina Industrial Commission. CPT Codes and Fees. Available at: http://www.ic.nc.gov/ncic/pages/00000a.htm. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- J Urgent Care Med. 2018 Urgent Care Chart Survey.

- CostHelper Health. How much do stitches cost? Available at: https://health.costhelper.com/stitches.html#extres4. Accessed January 23, 2020.