Urgent message: Rashes often lead patients to seek relief in the urgent care center. The ability to differentiate among common, superficial fungal infections and to select the most appropriate treatment or refer is an important skill to master.

Kosta G. Skandamis, MD and George Skandamis, MD

Introduction

Superficial fungal infections are among the most common skin conditions seen in the urgent care setting. Dermatophytes are the most common type of fungi that infect and survive on dead keratin (i.e., skin, hair follicles, nails), but certainly not the only type the clinician is likely to be presented with. Candidiasis, primarily due to Candida albicans, affects not only mucous membranes, but also skin (skin folds and moist areas). Finally, tinea versicolor (also known as pityriasis versicolor or, more colloquially, as yeast infection(is caused by the lipophilic yeast Pityrosporum, also known as Malassezia furfur.

In this article, we will review common causative organisms and discuss presenting characteristics, differential diagnosis, and available treatments.

Overview: Dermatophyte (Tinea) Infections

Three types of dermatophytes account for the majority of superficial fungal infections:

- Trichophyton

- Epidermophyton

- Microsporum

Dermatophytes can be classified according to the place of origin (anthropophilic, zoophilic, or geophilic), according to the tissue mainly involved (epidermomycosis, trichomycosis, or onychomycosis), or by body region affected (tinea faciale, corporis, cruris, manus, pedis).

It is not uncommon for dermatophyte infections to affect healthy individuals, but immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible.

Dermatophytes tend to present in children as scalp infections, while young adults are likely to have intertriginous infections. Gupta, et al, reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology that the prevalence of fungal nail infections is 0.7% in patients < 19 years of age, compared with 18% in patients 60 to 79 years of age.

The single most important test for diagnosis of dermatophytosis is the hyphae under the microscope. (See Table 1.) Cultures are usually unnecessary, since most species respond to many of the same agents.

| Table 1. Summary of Diagnostic Methods | |

| Infection | Methods |

| Tinea capitis | Black dot type Visualization of hyphae under the microscope or by fungal cultures.Gray patch type Direct visualization of hyphae under the microscope or by Wood’s lamp. Hairs infected with Microsporum spp fluoresce. |

| Tinea cruris | Direct visualization of hyphae under the microscope or by cultures (on Sabouraud’s medium). |

| Tinea pedis | Direct microscopy or fungal cultures. |

| Cutaneous candidiasis | Clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation or culture of scrapings. |

| Tinea versicolor | Identify round yeast and elongated hyphae “spaghetti and meatballs” on direct microscope examination of scales prepared with KOH or by the blue-green fluorescence of the scales under the Wood’s lamp. |

Tinea Capitis

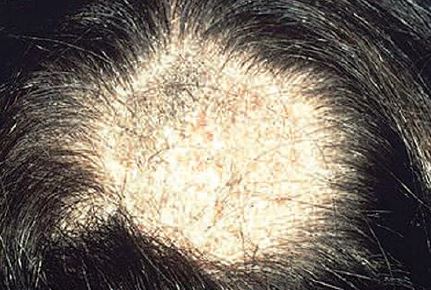

Tinea capitis affects children almost exclusively, and is much more common in African-Americans than in Caucasians. In adults, seborrheic dermatitis can mimic tinea capitis. Clinically, tinea capitis presents as two distinctly different forms:

- Black dot tinea capitis (BDTC) is the most common form of tinea capitis in U.S. and spreads from person to person by fomites (hats, combs, brushes, etc.). Small patches of asymptomatic, erythematous, scaling lesions can go unnoticed until alopecia develops. Broken-off hairs near the surface give the appearance of “dots” in dark-haired persons (hence, the name). (See Figure 1.)

Without treatment, BDTC progresses, leaving permanent scars. A secondary infection and transition to kerion may occur.

Diagnosis is only by visualization of hyphae under the microscope or by fungal cultures. A Wood’s lamp is not helpful.Gray patch tinea capitis (GPTC), caused by Microsporum canis, is usually contracted from dogs or cats and, rarely, from another person.

The infection starts as an erythematous, scaling, pruritic, well-demarcated circular patch, showing numerous broken-off hairs, that keeps spreading centrifugally. Many patches coalesce to form larger patches. Many patches may be present for weeks to months. (See Figure 2.)

Diagnosis is by direct visualization of hyphae under the microscope or by Wood’s lamp. Hairs infected with Microsporum spp fluoresce.

Occasionally, the lesion becomes boggy, waxy, purulent, and extremely tender and is associated with lymphadenopathy (kerion; see Figure 3).

Treatment

BDTC and GPTC both respond to the same medications (Table 2). Topical agents are ineffective.

Treatment of kerion is a subject of minor controversy. While some practitioners advocate treating with antibiotics active against Group A Strep and S aureus in addition to Griseofulvin 250 mg BID for four to six weeks plus hot compresses, others maintain that kerion can be treated successfully without antibiotics.

Table 2. Pharmacotherapy for BDTC and GPTC |

|||

| Dose* | Side effects | Noteworthy | |

| Griseofulvin | Adults For GPTC: 250 mg BID, 1-2 months; microsize 15 mg/kg/day up to 500 mg/dayFor BDTC: 250 mg TID, 6-12 weeks; ultramicrosize 10/mg/dayChildren 30-50-pound child: 125 mg- 250mg/day > 50-pound child: 250 mg – 500 mg/day |

Headache, nausea/vomiting, photosensitivity | CBC, LFTs if treatment lasts > 3 months |

| Terbinafine | Adults 10-20 kg: 62.5 mg/day, 4 weeks 20-40 kg: 125 mg/day, 4 weeks > 40 kg: 250 mg/day, 4 weeksChildren Not recommended |

Rarely, nausea, abdominal pain, aplastic anemia | |

| Itraconazole | Adults 200 mg/day, 4-8 weeksChildren 3-5 mg/kg/day, 4-6 weeks Or 5 mg/kg/day, 1 week each month for 2-3 months |

Needs acid gastric pH, raises levels of digoxin and cyclosporine | |

| Fluconazole | Adults and children 6 mg/kg/day, 2 weeks Repeat at four weeks if needed |

Only oral agent approved for children < 2 years | |

| CBC, complete blood count; LFT, liver function test *Variations on doing regimens exist in the literature. |

|||

Prevention

Examine school and home contacts to identify asymptomatic carriers. Carriers should be treated with selenium sulfide shampoo or with an oral antifungal agent. Children under treatment can return to school.

Tinea Corporis

Tinea corporis (TC, also referred to as ring worm) refers to dermatophyte infections of the trunk, legs, arms, and neck (excluding feet, hands, or groin), most commonly due to Trubrum. It affects all ages and can be transmitted by autoinoculation form other parts of the body, but also from close contact with animals or contaminated soil.

TC is more common in tropical and subtropical regions. It appears clinically as multiple, bright, mildly pruritic or asymptomatic sharply marginated, scaly plaques, with or without vesicles at the margin (Figure 4). These plaques enlarge peripherally with central clearing and production of concentric rings.

Allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and granuloma annulare all can mimic TC.

Tinea contact gladiatorum affects athletes who have skin-to-skin contact, and is caused primarily by Ttonsurans. In such case, the athlete should abstain from contact sports for 10 to 15 days.

Treatment

Tinea corporis usually responds well to topical antifungals, particularly the azoles. Systemic treatment is reserved for immunocompromised individuals, patients who failed topical treatment, and for TC gladiatorum.

Tinea Cruris

Tinea cruris (jock itch) refers to dermatophytosis of the groin, pubic area, and inner thighs. Primarily, it affects obese males who wear tight occlusive clothing in a humid, warm environment. Usually, it is associated with tinea pedis, often with a history of tinea cruris.

Clinically, tinea cruris presents as an erythematous patch on the inner aspect of one or both thighs. It spreads outward with central clearing and sharp, slightly elevated border which may or may not contain tiny vesicles. Scrotum and penis are rarely involved.

Differential diagnosis involves intertrigo, erythrasma, pityriasis versicolor, and psoriasis.

Diagnosis is achieved by direct visualization of hyphae under the microscope or by cultures (on Sabouraud’s medium).

Treatment

Tinea cruris responds well to topical antifungals, including azole and allylamine products, as well as ciclopirox and haloprogin. Failure to treat concomitant tinea pedis results in recurrence.

Prevention

Prevention is achieved by wearing shower shoes when using public baths, using antifungal powders to keep the groin dry, and avoiding hot baths and opting for boxer shorts instead of briefs. Wearing loose clothing may also be helpful. Also, avoid sharing fomites, like hats, clothing, and towels.

Tinea Pedis

Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot; see Figure 5) is the most common dermatophytic infection seen in practice. It involves the feet and is characterized by erythema, scaling, maceration, and/or bulla formation. The infection can, in time, spread to the groin, trunk, hands, and nails. Bacteria can invade through the cracks and cause cellulitis or lymphangitis.

Tinea pedis tends to be chronic, with exacerbations.

Males are more prone to tinea pedis than females. Hot, humid weather, occlusive shoes, and excessive sweating are other predisposing factors. Typically, tinea pedis is transmitted by walking barefoot on contaminated floors.

Skin lesions can be:

- interdigital type (dry scaling or macerated, peeling, fissuring of tow webs)

- mocasin type, which is the most difficult to treat (well=demarcated erythema with tiny papules and scales and being confined to heels, soles, and lateral borders of feet)

- inflammatory/bullous type (vesicles or bullae filled with clear fluid on soles, instep, web spaces)

- ulcerative type (extension of interdigital tinea infection onto dorsal and plantar foot, usually complicated by bacterial infections).

Differential diagnosis includes erythrasma, impetigo, Candida intertrigo, bullous impetigo, and dyshidorisis.

Diagnosis is established by direct microscopy or fungal cultures.

Treatment

Most topical agents (azoles, pyridines, allylamines, or benzylamines) applied BID for four weeks are effective against tinea pedis. Some prescription agents have a broader spectrum and can be applied once daily. A meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials concluded that treatment with terbinafine or naftifine. HCI produces a higher cure rate than treatments with itraconazole.

It should be noted that topical agents may be unable to penetrate keratinized plantar skin. In such cases, the oral form of these agents may be preferable.

Apply Burow’s wet dressings to macerated, interdigital lesions. Apply cool compresses and, if severe, add systemic steroids to acutely inflamed feet.

Prevention

Instruct patients to wear shower shoes in public baths and locker rooms. Wash feet with benzoyl peroxide after shower.

Tinea Manuum

Tinea manuum refers to a chronic dematophytosis of the hands that does not resolve spontaneously. Even after treatment, recurrences are common. Usually, the dominant hand is involved. tinea manuum can last for years.

On examination, hands look red with white scales confined to palmar creases (Figure 6). Borders are well demarcated with central clearing and pruritus is present.

Tinea manuum is usually associated with tinea pedis and/or tinea cruris and/or tinea unguium of fingernails.

Treatment

Because of the thickness of the palmar skin, topical agents are not effective. Use:

- terbinafine 250 mg QD for two weeks, or

- itraconazole 200 mg QD for one week, or

- fluconazole 200 mg QD for two to four weeks.

Cutaneous Candidiasis

Cutaneous candidiasis is a superficial skin infection affecting moist, macerated, chafed skin. Intertrigo refers to Candida infection on intertriginous areas (two closely opposed skin surfaces; see Figure 7). Factors that increase skin friction, moisture, warmth, or maceration and decrease immune response typically increase risk.

Clinically, the initial picture is one of an erythematous, pruritic plaque of the groin, perianal area, axilla, abdominal pannus, web space of toes and fingers, or under the breasts, with fine peripheral scaling and satellite pustules. Later, the plaques coalesce to form large eroded areas.

Diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation or culture of scrapings.

Treatment

The treatment is tailored toward the actual fungal infection, the underlying predisposing factors, and keeping the intertriginous areas as dry as possible.

Initial treatment for the majority of patients is a topical antifungal cream, typically miconazole or clotrimazole, applied for seven to 14 days. Oral antifungal agents (ketoconazole 22 mg/day or fluconazole 100 mg/day for four to six weeks) are reserved for resistant cases.

Various drying agents (e.g., corn starch, Domeboro’s solution, talcum powder, antifungal powders) can minimize skin fold moisture. Drying agents are used after adequate antifungal treatment has been completed. High-risk patients should use drying agents indefinitely, as well as antifungal cream once or twice a week.

Tinea Versicolor

Tinea versicolor is a chronic asymptomatic scaling dermatosis due to overgrowth of a yeast (Pityrosporum ovale) that resides normally in the keratin of skin and hair follicles. The term “tinea” should be reserved for dermatophytosis, and the present condition should be termed “pityriasis versicolor” (PV). Predisposing factors include humidity, high rate of sebum production, application of grease to skin, or high levels of cortisol.

PV presents as multiple, sharply demarcated hypopigmented macules with fine scales on the upper back, trunk, neck, arms, and abdomen (see Figure 8). The small macules are asymptomatic or may produce mild itching and can enlarge to form extensive patches.

Differential diagnosis includes vitiligo, pityriasis alba, psoriasis, and tinea corporis.

Diagnosis is achieved by identifying round yeast and elongated hyphae, so-called “spaghetti and meatballs,” on direct microscopic examination of scales prepared with KOH or by the blue-green fluorescence of the scales under the Wood’s lamp.

Patients should be informed that PV is not considered contagious, does not leave permanent scars, and that skin color alteration resolves within months.

Treatment

Selenium sulfide lotion applied to affected areas daily for two weeks is the mainstay of treatment.

Topical azole antifungal agents can be used once daily for two weeks.

Recurrence can usually be prevented by using any topical agent once weekly for the following few months.

Oral therapy is also effective (and sometimes preferred for its convenience), using:

- ketoconazole 200 mg/day for 10 days, or

- fluconazole 150 mg to 300 mg single dose/week for two to four weeks, or

- itranconazole 200 mg/day for seven days.

Oral therapy does not prevent recurrences.

Conclusion

Acute discomfort is often viewed as an urgent matter for which some may be disinclined to wait for a primary care appointment. Urgent care’s growth has been fueled by its ability to fill such gaps. Being prepared to provide relief with an accurate diagnosis and informed treatment choice for common, superficial fungal infections will help further establish the practitioners as an invaluable member of the healthcare “team.”