Differential Diagnoses

Retinoschisis

Choroidal detachment

Herpes simplex virus keratitis

Fungal keratitis

Diagnosis

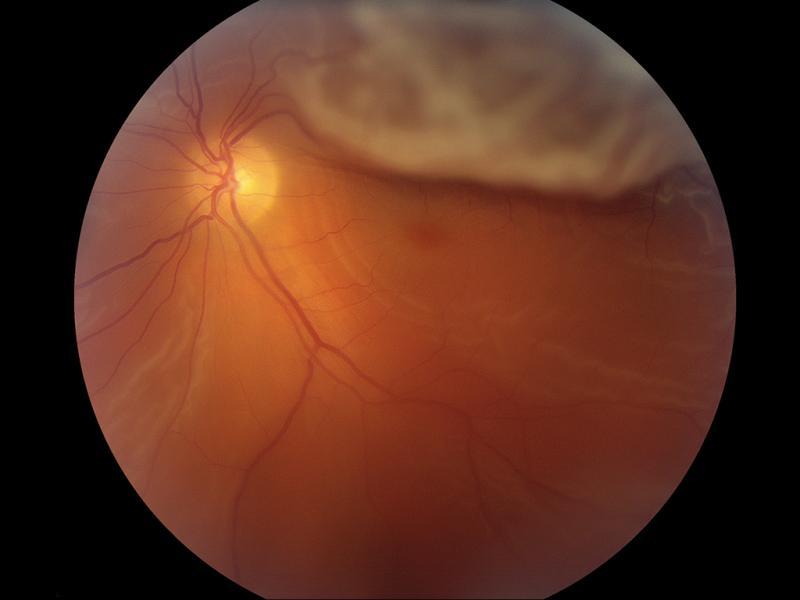

Retinal detachment

Learnings

Retinal detachment is a separation of the neurosensory retina from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), with an accumulation of fluid in the potential space between them. Normally, this potential space is closed because the RPE actively pumps fluid across the retina into the choroid.

Most retinal detachments are rhegmatogenous, meaning that they are caused by a break in the retina. Aging, surgical and nonsurgical trauma, high myopia, and peripheral retinal degeneration predispose the retina to these breaks. Posterior vitreous detachment is usually a benign condition associated with age and liquefaction of the vitreous, but its tractional force may lead to retinal breaks. Although most retinal breaks do not progress to retinal detachment, the prophylactic treatment available and the potential for vision loss signify the importance of detecting retinal breaks.

Retinal detachments can also be non-rhegmatogenous, caused either by leakage from beneath the retina (exudative) or by traction from scar tissue on the retina (tractional). Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, sickle cell retinopathy, and retinal vein occlusion can be associated with vitreous membranes that pull the neurosensory retina from the RPE.

Exudative detachments result when damaged RPE or retinal blood vessels allow fluid to pass into the subretinal space. It can be associated with ocular inflammation (uveitis, scleritis), neoplasms (choroidal melanoma, metastatic disease), vascular disease (Coats disease, malignant hypertension, eclampsia), maculopathies (central serous chorioretinopathy), and congenital disorders (optic disc pit, nanophthalmos). In exudative retinal detachments, subretinal fluid shifts with head position, and visual disturbances may be positional.

Patients who see photopsias (flashes of light) or floaters are at an increased risk of developing retinal breaks and detachments. There should be a high suspicion of progression to retinal detachment when bright flashes are accompanied by a shower of black dots or a curtain or black shadow blocking the vision.

The overall annual incidence of retinal detachments is approximately 1 in 10,000. Although most detachments can be successfully repaired anatomically, only those treated early avoid permanent visual impairment. Retinal detachments can progress to involve the macula within hours, often leading to visual loss even when repaired properly.

What to Look For

Vision loss, visual field loss, and blood or pigment cells in the vitreous are signs that can be associated with a retinal detachment.

In rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD), a full-thickness break is associated with elevation of the retina by the subretinal fluid nearby. The detached segment of retina looks more opaque and wrinkled. When the eye moves in a recent RRD, the detached area undulates.

The retina retains its transparency in exudative retinal detachments. Here, smooth dome-shaped areas of elevated retina may shift with changes in the patient’s head position. Tractional retinal detachments appear as fixed concave areas with retinal striae radiating from the region of greatest traction.

A long-standing detachment may appear transparent and fixed and often has a demarcation line of dark pigment. It may also be associated with retinal neovascularization, cataract, uveitis, rubeosis iridis, and retinal cysts.

Acknowledgment: Image courtesy of Logical Images, Inc. (www.VisualDx.com/JUCM)