Urgent message: To better evaluate and treat patients with low back pain, urgent care providers need a good understanding of the anatomy of the back and they must be vigilant for “red flags” that signal a potentially serious condition.

SHAILENDRA K. SAXENA, MD, PHD, MIKAYLA SPANGLER, PHARM D, BCPS, and SANJEEV K. SHARMA, MD, MBA

Introduction

Acute low back pain is a common condition often seen by urgent care providers. An episode of acute low back pain is usually of short duration and many patients will recover without any therapeutic intervention. The challenge for a provider is to manage low back pain effectively while limiting diagnostic evaluations and providing adequate conservative treatment. At the same time the provider needs to be vigilant about red flags associated with low back pain that may require further work up and referral to a spine specialist. This article is a comprehensive review of evaluation and treatment of low back pain and red flags associated with it. It should be noted that red flags may not necessarily indicate serious pathology, but providers should rely on a comprehensive clinical approach to evaluation of the condition.

Incidence and Anatomy of Low Back Pain

Lifetime prevalence of low back pain is as high as 84%, and it is reported to be the second most common reason for office visits in the United States.1 Most patients are likely to experience one episode of low back pain during their adult lives.2 It can affect individuals at any age, but it is most often seen between ages 20 and 40, with an equal gender distribution.2

The anatomy of the back is complex. To understand the pathophysiology of low back pain, a thorough knowledge of the anatomy is necessary.

A typical vertebra consists of a vertebral body, a vertebral arch and seven processes (a spinous process, two transverse processes and four articular pillars).3 The intervertebral disc is interposed between the vertebral bodies. The outer ring of the disc is fibrocartilage (anulusfibrosus) while the central core is fleshy (nucleus pulposus). Herniation or protrusion of the nucleus pulposus into or through the annulus fibrosus and com- pressing the nerve roots is a well-recognized cause of low back pain (Sciatica). The laminae of adjacent vertebral arches are joined by the yellow ligament, the ligamentum flavum, which assists with straightening of the vertebral column after flexing. Hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum is another common cause of low back pain (lumbar stenosis).

Several ligaments and extrinsic and intrinsic back muscles are attached to the spinous and transverse processes. They are necessary to support and move the vertebral column. Minor sprains of these ligaments and muscles are also a common cause of low back pain (muscle sprain). The spinal nerve roots of the lumbar and sacral spinal nerves are the longest and descend in the lumbar cisterns before exiting through the intervertebral foramina. Compression of these nerve roots may cause low back pain and saddle anesthesia in the perineum (Cauda Equina Syndrome).

Preparation for Clinical Evaluation

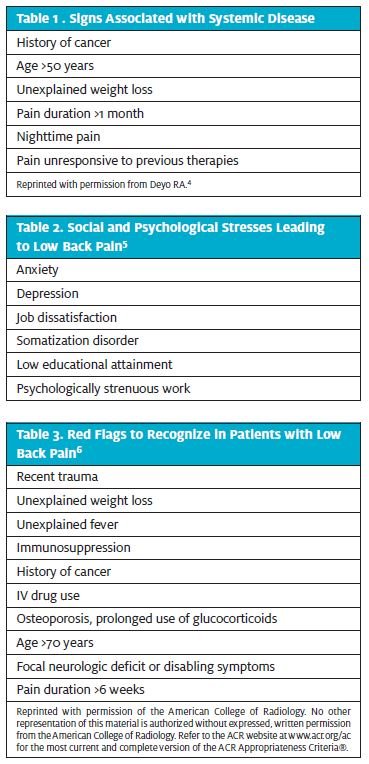

Acute low back pain often is non-specific but urgent care providers should nonetheless be prepared to take a detailed history aimed at identifying specific causes, especially those associated with systemic and anatomical pathology. They should look specifically for signs and symptoms associated with systemic diseases (Table 1), social and psycho- logical stresses (Table 2), and risk factors that may be contributing to a patient’s low back pain. In addition, red flags (Table 3) that may be indicative of a serious cause of low back pain also should be evaluated.

Evaluation of Symptoms and Correlation with Anatomy

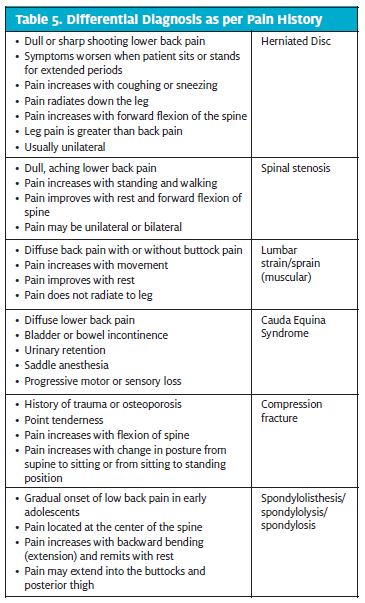

Patient evaluation begins with characterization of the pain (Table 4) to establish the diagnosis. It should be noted that before presenting in the urgent care setting, many patients will have already tried non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medications and heat or cold packs. Patients often report pain radiating to the leg (radiculopathy) but pain radiating below the knee is a more important sign of true radiculopathy than that radiating to the thigh.7

Physical Examination

Physical examination of the back should be an important part in the evaluation of low back pain. Inspection of the back should be done to look for rash (Herpes Zoster), scoliosis or asymmetry of muscle mass and tone (muscle spasm). It may be possible to elicit point tenderness (compression fracture) or costovertebral angle tenderness (urinary tract infection/pyelonephritis). Most patients may be unable to perform movements of the spine. Attempts should be made, however, to check spinal movement (whatever possible) to determine whether pain is related to vertebral discs (pain in forward movement), spinal stenosis (pain in backward movement) or related to muscle spasm (pain in all movements).

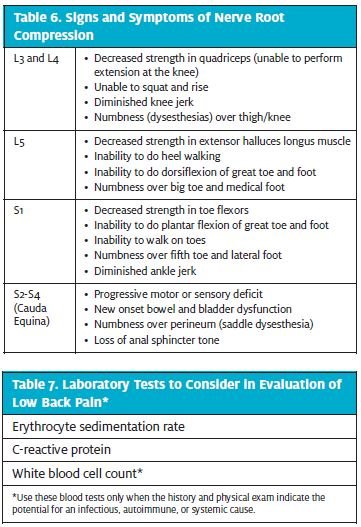

A straight-leg raise (SLR) test—also known as Lasegue’s sign/test—should be performed to determine whether disc herniation is the cause of low back pain. With the patient supine position on the table and the uninvolved knee bent to 45°, the provider should hold the involved leg straight, hold the heel with the other hand in the dorsiflexed position, and gently raise the leg. The SLR test is positive if the patient has pain in the distal leg with leg elevation between 30° and 70°. A crossed SLR also should be performed. The test is positive when the physician lifts the unaffected leg and the patient has pain that radiates below the knee in the affected leg.2 All efforts should be made to determine the site of nerve root compression in the lumbar area (Table 6). However, it should be noted that the value of these tests declines with advancing age.

Laboratory and Radiographic Testing

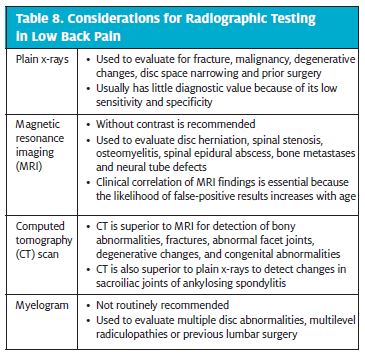

Patients with low back pain of less than 6 weeks’ duration should be treated conservatively unless red flags are pres- ent.6 Imaging is not warranted for most patients with acute low back pain. Without signs and symptoms indicating a serious underlying condition, imaging does not improve clinical outcomes in these patients. For even patients with a few of the weaker red flags, 4 to 6 weeks of treatment is appropriate before imaging studies are considered. Several laboratory studies and radiographic tests, however, can be used to evaluate low back pain.

Tables 7 and 8 list these studies and tests but urgent care providers are advised to consult published guidelines to determine when they are appropriate for a particular patient.8,9

Management

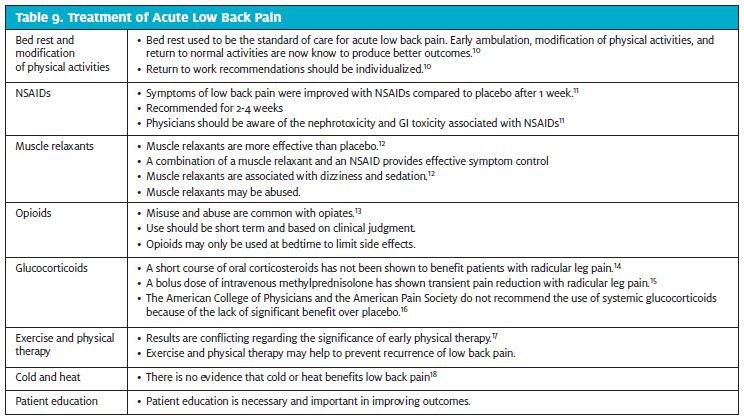

Numerous treatments have been recommended for acute low back pain. Each has its own merits and demerits. It is, however, good news for urgent care providers to know that the prognosis for acute low back pain is excellent and up to 90% of patients will improve on their own.9 Treatment protocols for acute low back pain are summarized in Table 9.

Discussion

Acute low back pain that is uncomplicated (i.e., no red flags) is a self-limiting condition that does not require imaging or laboratory studies. In our opinion, urgent care providers need a good understanding of the anatomy of the back to better evaluate and treat patients with acute low back pain. They should also be vigilant to note red flags associated with a patient’s low back pain.

Besides the treatments mentioned in table 10, many other strategies have been recommended for acute low back pain. These include spinal manipulation, massage and yoga, acupuncture, traction, and braces.19 Unfortunately, none of these has been shown to improve back pain significantly over placebo. Epidural steroid injections also have been used to treat low back pain but. However, they have only been shown to improve symptoms for a short duration and have not been shown to be more effective than systemic corticosteroids.20,21 In conclusion, it appears that short-term treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with or without muscle relaxants and patient education are key in the management of acute low back pain in urgent care.

- Deyo RA, Tsui-Wu Descriptive epidemiology of low-back pain and its related med- ical care in the United States. Spine. 1987;12:264-268.

- Helfgott Diagnosing and managing low back pain. Cortlandt Forum. November 2005;24-34.

- Moore KL and Dalley Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Fourth Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 1999. pp. 437-8.

- Deyo Early diagnostic evaluation of low back pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1:328- 338.

- Skovron ML, Szpalshi M, Nordin M, Melot C, Cukier Sociocultural factors and back pain. A population-based study in Belgian adults. Spine. 1994;19:129-137.

- Low back American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Avail- able at http://www.acro.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/Low- BackPain.pdf. Accessed 3/27/13.

- Deyo RA, Loeser JD, Bigos Herniated lumbar intervertebral disk. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:598-603.

- Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systemic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:463-72.

- Casazza Diagnosis and treatment of acute low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:343-350.

- van der Giessen RN, Speksnijder CM, Helders The effectiveness of graded activ- ity in patients with non-specific low-back pain: a systemic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1070-106.

- Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder Non-steroidal anti-inflam- matory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review Spine. 2008;33:1766-1774.

- van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter Muscle relaxant for non- specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD004252.

- Compton WM, Volkow Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:103-107.

- Holve RL, Barkan Oral steroids in initial treatment of acute sciatica. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21:469-474.

- Finckh A, Zufferey P, Schurch MA, Balaque F, Waldburger M, So Short-term effi- cacy of intravenous pulse glucocorticoids in acute discogenic sciatica. A randomized con- trolled trial. Spine. 2006;31:377-381.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478-491.

- Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battie M, Street J, Barlow A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1021-1029.

- French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, Reggars JW, Esterman Superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004750.

- Posadzki P, Ernst Yoga for low back pain: a systemic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30;1257-62.

- Carette S, Leclaire R, Marcoux S, et Epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica due to herniated nucleus pulposus. N Eng J Med. 1997;336:1634-1640.

- Nelemans PJ, de Bie RA, de Vet HC, Sturmans Injection therapy for subacute and chronic benign low back pain. Spine. 2001;26:501-515.