Urgent message: From pregnancy confirmation to the evaluation of bleeding, urgent care centers are often the initial location for management of obstetric issues. Careful use of evidence-based guidelines is the key to successful outcomes.

DAVID N. JACKSON, MD, FACOG

Introduction

Although close to 160 million visits are made to urgent care providers each year in the United States, there are currently no prospective studies describing how pregnancy may initiate or complicate an urgent care consultation. Until further research is available, this article hopes to provide the urgent care practitioner with evidence based guidelines for common pregnancy related issues, from confirmation of pregnancy through infections and illnesses related to gestation.

The Most Common Complaints

An internal audit of our quick care system performed in 2012 found that vaginal discharge, urinary tract infections (UTIs), hyperemesis, vaginal bleeding, and abdom- inal pain were the most common pregnancy-related issues. Perez reported that vaginal bleeding, postpartum care, pelvic pain, and pelvic or vaginal infections were the most common “urgent care” complaints in a system specializing in ob/gyn.1 These limited experiences encompass only a fraction of syndromes likely to be encountered in urgent care pregnancy services. Part 1 of this two-part series will discuss:

- Pregnancy confirmation

- Genitourinary infections

- Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Vaginitis and cervicitis

- Pediatric illness with pregnancy risks

Part 2 will review:

- Pregnancy bleeding

- Preeclampsia

- Minor trauma

- Abdominal pain

- Medication use in pregnancy

Pregnancy Confirmation

Pregnancy detection is frequently offered in urgent care.2 We reviewed 50 consecutive web pages advertising urgent care services, and 80% confirmed that rapid “walk-in” pregnancy testing was available. Because urine tests begin to discriminate hCG levels at 25 to 32 days after the last menstrual period (LMP), a negative urine test should be repeated if it has been less than 30 days from the previous LMP. For any patient in whom bleed- ing, pain, or symptoms suggest ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, or molar gestation, an urgent care practitioner should preferentially recommend a quantitative serum hCG. This allows for serial comparison of hCG rise or fall in subsequent visits.

Urinary Symptoms in Pregnancy

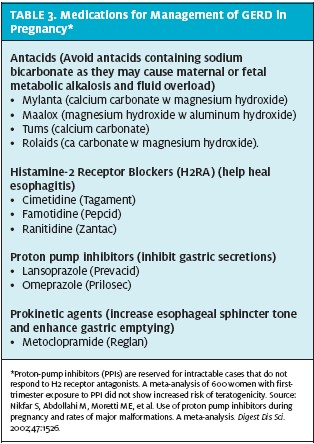

Acute symptomatic cystitis develops in only 1% of pregnant patients. Any patient with dysuria, urgency and/or hematuria during pregnancy should be evaluated with urinalysis and culture. Approximately 80% of positive cultures will return E coli. The remainder typically includes Proteus species, Klebsiella pneumoniae, group B streptococci, enterococci, and staphylococci. Table 1 lists antibiotics appropriate for use in treatment of acute cystitis in pregnancy. All should be used for 7-14 days, followed by a test of cure 1 week after completion of the antibiotic course.

Uncomplicated urinary colonization in pregnancy. Pregnant patients without symptoms may test positive for leukocyte esterase or nitrites on urine dipstick obtained routinely during an urgent care visit. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is confirmed by the presence of >100,000 organisms/mL in midstream urine culture. If untreated, up to 25% of these patients will progress to pyelonephritis and have significant risk of morbidity. Treatment reduces pyelonephritis by 80% and reduces preterm delivery by 40%. Typical treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria is 5 to 7 days followed by culture for cure. Because urine dipstick has high sensitivity but poor specificity, each urgent care center should decide if all pregnant women require midstream urinalysis and culture for asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Nitrofurantoin for asymptomatic bacteria appears safe in all trimesters of pregnancy. Nitrofurantoin is not active against Proteus spp. Alternative therapies are 3 to 7 days of sulfisoxazole (500 mg 4 times a day) or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) daily or cephalexin (250 to 500 mg 4 times a day). Emerging high resistance rates limit amoxicillin use (250 mg 3 times a day) as a single agent unless sensitivities indicate efficacy. Cephalexin is not active against enterococcus and should not be used if enterococcus is identified.3 TMP-SMX should theoretically be avoided late in gesta- tion because of the sulfonamides’ ability to displace bilirubin from albumin-binding sites and cause neonatal jaundice.

If Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is identified, counseling includes treatment with antibiotics at the time of diagnosis. Such patients also should be flagged as high risk and requiring intrapartum antibiotics to decrease early- onset neonatal sepsis.

If culture for cure shows persistent colonization, or if recurrent infections occur, chronic suppressive therapy with nitrofurantoin, 100 mg q hs, is indicated.

Pyelonephritis. Up to 2% of pregnancies are complicated by pyelonephritis. The release of endotoxins causes patients to present with fever, leukocytosis, and kidney tissue inflammation, producing the classic symptoms of flank pain and costovertebral angle tenderness (CVAT). Symptoms in pregnancy are also characterized by a 1- to 3-day history of chills, urinary frequency, and nausea with emesis. Urinalysis will show significant bacteriuria and leukocytes. Patients in an urgent care center who are suspected of having pyelonephritis in pregnancy should be referred for immediate inpatient management to monitor for sepsis, premature labor, or progression to significant maternal respiratory distress from adult respiratory distress syndrome. The most common recovered organism in pyelonephritis in pregnancy is E. coli and therapy requires intravenous antibiotics until asymptomatic, followed by 10 days of oral therapy. After acute hospital treatment, suppressive outpatient therapy with macrodantin is often indicated to avoid recurrent UTI in pregnancy.

Warning: A suspicion of UTI is often the initial incorrect diagnosis for appendicitis in pregnancy. Up to 20% of pregnant patients with appendicitis present with pyuria and/or hematuria. In these patients, nausea, vomiting, and right lower quadrant or flank pain worsens as peritoneal signs develop.

Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy

“Morning sickness” is the stereotypical symptom that lay people use to define early pregnancy. The progression to persistent vomiting with ketonuria and weight loss requires intensive evaluation and management.

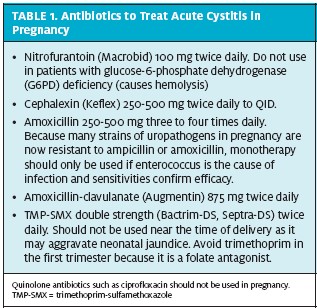

Several clinical pearls will help the urgent care practitioner discern nausea and vomiting of pregnancy from the differential seen in Table 2. History determines if chronic gastrointestinal (GI) conditions precede and then continue with pregnancy. Abdominal pain is not typical with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. The presence of abdominal pain (with or without fever) suggests a GI pathology and WBC count, metabolic panel, and abdominal ultrasound should be considered. Acute nausea and emesis after 9 weeks is also suggestive of GI pathology, and hepatitis should always be considered in patients with loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice. Headache is not typical with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and a complete neurologic exam is mand tory. Molar gestation should be considered and con- firmed or ruled out with ultrasound and quantitative hCG. Goiter suggests thyroid disease to be confirmed with free T3, free T4, and TSH analysis.

When acute care physicians undertreat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, the impact is extreme. A 1997 study by Mazzota indicates that fewer than 50% of women who terminated their pregnancies because of severe nausea and vomiting had been offered any sort of antiemetic therapy. Of those offered treatment, 90% were offered regimens that were not likely to be effective.4 This would be unacceptable in today’s setting of evidence-based guidelines, which make the following recommendations, based on consistent scientific evidence (Level A):5

- It is important to note that Zofran (Ondansetron) is not the first line therapy in nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Vitamin B6 or vitamin B6 plus doxylamine is safe and should be considered first- line Doses are Vitamin B6, 10 to 25 mg, 3 or 4 times per day and doxylamine, 12.5 mg, 3 or 4 times per day. The combination of doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine hydrochloride (vitamin B6), has recently been approved by the FDA for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Duchesnay USA has announced the availability of Diclegis a composition of 10 mg doxylamine succinate and 10 mg pyridoxine hydrochloride in US pharmacies. Large-scale efficacy studies are anticipated within the next few years.

- Second-line therapy is to add promethazine, 12.5 to 25 mg every 4 hours, orally or rectally or dimen- hydrinate, 50 to 100 mg every 4 to 6 hours, orally or rectally (not to exceed 400 mg per day; not to exceed 200 mg per day if patient also is taking doxylamine).

- In patients who have no dehydration, third-line ther- apy is any of the following: Metoclopramide, 5 to 10 mg q8 hrs, IM or po or promethazine, 5 to 25 mg every 4 hours, IM, orally, or rectally or trimethoben zamide, 200 mg every 6 to8 hours, rectally.

- In patients who have dehydration, IV fluids should be administered, plus any of the following: Dimenhydrinate, 50 mg (in 50 mL saline, over 20 min) every 4 to 6 hours, intravenously (IV) or metoclo- pramide, 5 to 10 mg every 8 hours IV or pro- methazine, 5 to 25 mg every 4 hours, IV.

- Ondansetron, 8 mg, over 15 minutes, every 12 hours,

- Additional therapies with intensive counseling typically require inpatient

Alternative therapies.

The P6 acupressure wristband and acustimulation can be considered as alternative nonpharmacologic therapies. Alternative pharmacologic therapies include ginger capsules (250 mg 4 times daily), methylprednisolone (16 mg every 8 hours, orally or IV, for 3 days. Taper over 2 weeks to the lowest effective dose). Corticosteroids should be considered as a last agent prior to enteral nutrition. Patients should respond within 3 days. In those who respond, the lowest effe tive dose should be continued for not longer than 6 weeks. Concern over fetal facial clefts has been suggested in animal studies only.

GERD in Pregnancy

Reflux of acid from the stomach into the esophagus is common in pregnancy because of decreased esophageal sphincter tone, elevation of the organs in the maternal 2007 issue of JUCM (https://www.jucm.com/magazine/ issues/2007/0607/). Diseases presenting with a chief complaint of vaginal discharge include bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and vulvovaginal candidiasis.

The standard approach to evaluation includes physical exam, wet prep, and cultures. An urgent care provider should first look within the vagina and sample the vaginal discharge. Normal vaginal discharge is clear and odorless. Ph is typically basic and litmus paper testing shows vaginal pH greater than 4.5. To complete a wet mount, a swab of the vaginal discharge is placed on a microscope slide and suspended in saline solution.

Any history of slow, constant leakage or dampness may represent premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and should be considered when evaluating vaginal discharge in pregnancy.

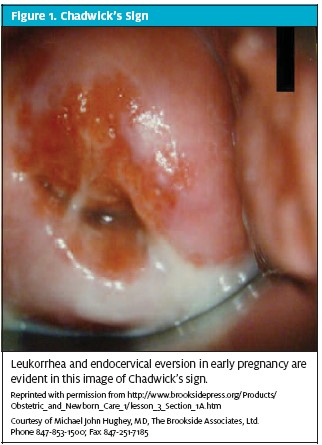

Normal pregnancy changes: Chadwick’s sign and cervical eversion. Chadwick’s sign in early pregnancy is represented by increased vascularity, which causes the vaginal walls to become a darker color (Figure 1). There is eversion of the endocervix and an increase in mucoid discharge (leukorrha). These signs often give the false impression of a pathologic cervical-vaginal infection. One area of caution is that signs of cervical dilatation from cervical incompetence also include increased vagi- nal discharge. This usually occurs at 16 to 22 weeks and may be associated with backache, pelvic pressure, and scant bleeding. Speculum exam may show cervical dila- tion and exposed membranes. Ultrasound will show cervical shortening and funneling.

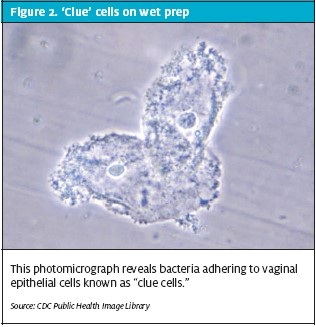

Bacterial vaginosis. Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus, Bac- teroides, and Mycoplasma make up the bacterium implicated in a common infection known as bacterial vaginosis (BV). Bacterial vaginosis is an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria and a decrease in the normal lactobacillus flora.Physical exam discloses a thin, grey, watery, frothy discharge that has a characteristic “fishy” odor when combined with a 10% potassium hydroxide solution. This strong amine smell with KOH is a positive “whiff test.” The vaginal pH is typically above 4.5. On wet prep the epithelial cells are coated with bacteria, obscuring the epithelial borders and imparting an appearance commonly referred to as “clue” cells (Figure 2). BV has been associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm PROM, preterm labor, and intrapartum infection. Asymptomatic, at-risk women with a history of prior preterm delivery should be screened for BV at approximately 24 weeks’ gestation and treated if the infection is diagnosed. Symptomatic patients should be promptly evaluated at any gestational age and treated if wet mount, rapid test, or culture are positive.7,8 Recommended treatment regimens are metronidazole (500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days) or metronidazole (250 mg orally three times a day for 7 days) or clindamycin (300 mg orally twice a day for 7 days).7 Doxycycline, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin are contraindicated in pregnant women.

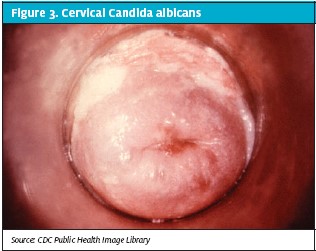

Candida. Vulvovaginal candidiasis frequently occurs during pregnancy. Candida albicans is a diploid fungus that grows both as yeast and filamentous cells and it is the etiologic agent responsible for candidiasis (Figure 3). The features of vulvovaginal candidiasis include pruritis, erythema, and discharge. The discharge is typically thick and white or yellowish. Inflammation of the walls of the cervix, vagina and of the vulva (external genital area) causes burning and itching.

Topical azole therapy applied for 7 days is the most frequently recommended therapy for pregnant women. Over-the-counter intravaginal agents that can be used are clotrimazole 1% cream (5 g intravaginally for 7 days) or miconazole 2% cream (5 g vaginally for 7 days) or miconazole (100 mg vaginal suppository, one for 7 days). Prescription agents include terconazole (0.4% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7 days). Only topical azole therapies are recommended by the CDC for use in pregnant women. Oral luconazole (150 mg oral tablet, one tablet in a single dose). Is category C and is typically ordered for medically compromised patients (diabetics, immunocom promised) or those with recurrent candidiasis.

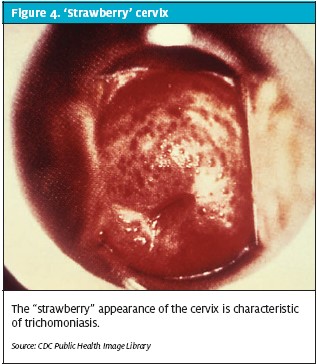

Trichomoniasis. Trichomonas vaginalis is a pear-shaped mobile protozoan parasite with flagellae. Infection is char- acterized by a greenish to yellow odorous vaginal dis- charge with a frothy appearance. Prevalence of T vaginalis infection has been estimated as high as 9% to 22% in pregnant women. Patients will complain of itching, dyspareunia, and/or dysuria from vulvar irritation. The cervix has a characteristic “strawberry” appearance (Figure 4). The diagnosis is typically made by seeing motile protozoa on wet mount light microscopy or rapid testing. Testing should be offered together with testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Up to 17% of neonates born to untreated mothers will be infected. Women can be treated with 2 g metronidazole in a single dose at any stage of pregnancy. Metronidazole 500 mg BID for 5 to 7 days is an alternative Partners should also be treated to avoid recurrence of this sexually transmitted disease. Rapid tests. The Affirm™ VPIII Microbial Identification Test (BD) is a single-sample DNA probe for identification of Candida spp, G vaginalis, and T vaginalis. Results are available in less than 60 minutes. The OSOM® Tri- chomonas Rapid Test (Genzyme Diagnostics) is an anti- gen-detecting test for trichomoniasis that can be completed in 10 minutes. The vaginal swab is placed within the buffered test tube, mixed vigorously by hand, and then a test strip is inserted for results.

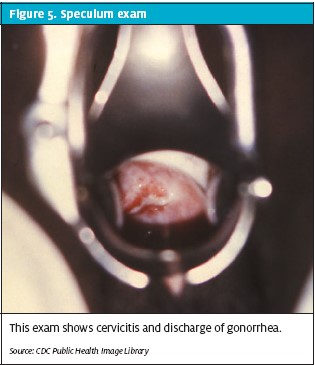

GC and Chlamydia. Both chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae selectively invade the endocervical epithelial cells, causing endocervicitis (Figure 5). Both pathogens may be asymptomatic. Women at highest risk are those aged 25 years, those with more than one sexual partner, with a history of sexually transmitted infection or drug use, and those seen in emergency settings for vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain in pregnancy.

All pregnant women should be routinely screened for Chlamydia trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae during pregnancy, usually at the first prenatal visit.7If an urgent care visit occurs before this screening, a high degree of suspicion should be main- tained because C trachomatis is the most common sexually trans- mitted pathogen in the United States. In pregnant women, these infections can be associated with ectopic pregnancy, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), and pre- mature delivery.

Treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy is with azithromycin (1 g orally in a single dose) OR amoxicillin (500 mg orally three times a day for 7 d) or erythromy abdomen, and decreased gastric motility. Repeated reflux leads to esophageal inflammation. Sleep may be disturbed as symptoms of epigastric pain and burning progress. cin base (500 mg orally four times a day for 7 days) OR erythromycin ethylsuccinate (800 mg orally four times a day for 7 days). There is up to a 10% failure rate with initial treatment, A test of cure should be done 2 to 3 weeks after the initial treatment and patients should be retest- ed 3 months after treatment.7 In nonpregnant patients, tetracycline and doxycycline show the greatest activity against chlamydia; however, these agents are contraindicated in pregnancy. The patient’s partner should always be treated, and tetracycline or doxycycline is appropriate. N gonorrhoeae can produce devastating sequelae to the female upper genital tract. The cervicitis has an extensive mucopurulence from the cervical os and often fri- ability with bleeding when touched.

The updated recommendation for treatment of N gonorrhoeae in pregnancy is with ceftriaxone (250 mg in a single intramuscular dose) PLUS azithromycin (1 g orally in a single dose). Alternative regimens if ceftriax one is not available are cefixime (400 mg in a single oral dose) PLUS azithromycin (1 g orally in a single dose). A “test-of-cure” should occur within 1 week. If a patient with N gonorrhoeae has severe cephalosporin allergy, treat with azithromycin (2 g in a single oral dose) with test-of-cure in 1 week. Either azithromycin or amoxicillin is added for treatment of presumptive C trachomatis infection when N gonorrhoeae is found during pregnancy (see Chlamydial Infections).

Pregnant women found to have gonococcal infection during the first trimester should be treated and retested in the third trimester. Uninfected pregnant women who remain at high risk of gonococcal infection should also be retested during the third trimester.6 All patients with gonococcal infection should be reported to the state health agency. Screening for other sexually trans- mitted diseases such as chlamydia and syphilis is appropriate. Partners also require full treatment.

Syphilis. Patients with primary syphilis may present with lesions on the vulva, but the cervix typically has no lesions. Inguinal adenopathy is often present. Laboratory evaluation of a patient with a suspicious vulvar lesion should include rapid plasma reagin test with reflex treponemal testing, herpes simplex virus culture, and HIV testing. If the T. pallidum particle agglutination test result is positive, a patient should receive 2.4 MU benzathine penicillin G. If a patient is allergic to penicillin, she should be hospitalized for controlled desensitization as the standard of care treatment for syphilis and pregnancy.6

Pediatric Illness With Pregnancy Risks

Urgent care services are becoming the location for first line evaluation of febrile illness in a young child.8 The urgent care practitioner should be cautious to warn parents of reproductive age about the risks of cytomegalovirus, parvovirus, TORCH infections, and Influenza. Not only is the pregnant patient at risk of severe illness due to the relative immunocompromised state of pregnancy, but the developing fetus is at risk of multiple syndromes as outlined below.

Influenza. Influenza season brings a 26.0% patient volume increase in pediatric urgent care. In fact, pediatric urgent care centers now see a larger portion of the bur- den of H1N1 influenza than does the pediatric emergency department.9 Influenza vaccination is specifically recommended in pregnancy to protect the mother and to enhance childhood immunity. Influenza vaccination is recommended in all trimesters. This protects the mother and also results in decreased febrile respiratory illnesses in the newborn, likely through passive antibody transfer.

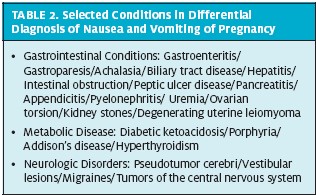

Lifestyle and diet counseling are first-line therapy. Measures to reduce smoking are essential. Avoidance of greasy, acidic, or spicy foods will reduce reflux. Raising the head of the bed and avoiding lying down for 3 hours after eating may be helpful. Scheduled use of over-the- counter antacids is safe for immediate relief.

Table 3 lists medications appropriate for treatment of GERD in pregnancy.

Vaginitis and Cervicitis in Pregnancy

One of the most common complaints leading to medical consultation in pregnancy involves symptoms suggestive of vaginal or cervical infection. Inflammatory changes of the vulva or vagina will produce redness, swelling, itching, and various types of discharge. A concise review of vulvovaginitis can be found in the June tion receive prompt antiviral therapy with Tamiflu (oseltamavir) or Relenza (zanamivir). Parvovirus.The best test to confirm the diagnosis of maternal infection following exposure to the affected child would be IgM and IgG serology. The most likely severe fetal complication of this infection is hydrops. Varicella. A child with chickenpox is contagious from 1 to 2 days before the rash appears until all blisters have formed scabs. The mother may develop chicken- pox 10 to 21 days after contact with the infected child. Pregnant women who get varicella are at increased risk of developing pneumonia and meningitis. Counseling in the urgent care center includes warnings that symptoms of cough or headache should prompt immediate evaluation. For adults with varicella pneumonia or meningitis, immediate hospitalization and antivirals are required to reduce the 10% to 25% mortality associated with this syndrome in pregnancy.

If a pregnant woman gets varicella in her first or early second trimester, the fetus has a 0.4% to 2.0% risk of being born with congenital varicella syndrome. The baby may have scarring on the skin leading to contractures, abnormalities in limbs, brain, eyes, and low birth weight.

For pregnant mothers exposed to varicella, maternal varicella antibody can be evaluated to confirm IgG and IgM status. The majority of women will be immune, even those with no recollection of prior varicella infection. Presumed evidence of protection includes docu- mentation of two prior doses of varicella vaccine, a maternal serum blood test showing immunity to vari- cella, or verification of a history of chickenpox or her- pes zoster.

If a woman develops varicella rash from 5 days before to 2 days after delivery, the newborn will be at risk for neonatal varicella. In the absence of treatment, up to 30% of these newborns may develop severe neonatal varicella infection. Therefore, newborns of mothers with confirmed or suspected varicella require careful fol- low-up and potential treatment with antivirals.

Any woman found to be at risk of varicella should receive varicella vaccine. However, the live attenuated virus should not be given during pregnancy. As soon as a pregnant woman( who is not protected against chick- enpox) delivers her baby, she should be vaccinated.. The vaccine is safe for mothers who are breastfeeding.

CMV. CMV is the most common viral cause of con- genital infection. The fetus may show echogenic bowel and symmetrical intrauterine growth restriction. Transmission occurs primarily through contact with children actively shedding the virus in nasopharyngeal secretions, urine, saliva, tears, genital secretions, breast milk or blood. After primary infection during pregnancy, the rate of transmission to the fetus ranges from 15% to 50% and sequelae include congenital mental retardation and deafness. Pregnant women should minimize close contact with infectious children. Frequent hand washing and appropriate handling of potentially infectious secretions have been shown to be effective in minimizing viral transmission.

Pertussis immunization with Tdap is now recommended for all pregnant women during the late sec- ond (>20 weeks) or third trimester, with the intent to both protect the mother and provide passive antibody to their infants before vaccination at age 2 months. Provider support for these recommendations regard- ing both annual influenza vaccination and postpartum Tdap vaccination during pregnancy is felt to be critical to improve both maternal and fetal health.10 This is supported by the CDC and ACOG. Health care personnel should administer a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy irrespective of the patient’s prior his- tory of receiving it. To maximize the maternal anti- body response and passive antibody transfer to the infant, optimal timing of Tdap administration is between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation, although Tdap can be given at any time during pregnancy.

For women not previously vaccinated with Tdap, if it is not administered during pregnancy, it should be administered immediately postpartum.11

References

- Perez M, Nelson Assessment of urgent and ongoing contraceptive needs in an OB/GYN urgent care setting. Contraception. 2007;75(2):108-111.

- Hochman E, Elami-Suzin M, Soferman HG, et Early pregnancy confirmation—the role of urine pregnancy test in military primary care clinics. Mil Med. 2012;177(8):947-951.

- Dashe JS, Gilstrap LC Antibiotic use in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:617–629.

- Mazzota P, Magee L, Koren Therapeutic abortions due to severe morning sickness. Unacceptable combination. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:1055–1057.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin 52. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:803–815. (reaffirmed 2011)

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR. December 17, 2010 / Vol. 59 / No. RR-12

- Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, Milan Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000262.

- Maguire S, Ranmal R, Komulainen S, et Which urgent care services do febrile chil- dren use and why? Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(9):810-816.

- Conners GP, Hartman T, Fowler MA, Schroeder LL, Tryon Was the pediatric emer- gency department or pediatric urgent care center setting more affected by the fall 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(8):764-766.

- Fortner KB, Kuller JA, Rhee EJ, Edwards KM. Influenza and tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccinations during Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67(4):251-257.

- Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria tox- oid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women – Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR 2013; 62 (07):131-5.