Physical Examination

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs are as follows:

- Temperature: 98.4°F (36.8°C)

- Pulse: 108 beats/min

- Respiration: 24 breaths/min

- Blood pressure: 162/88 mm Hg

- Oxygen saturation: 100% on room air

The patient reports no significant issues in his medical history. He is a smoker. He is alert and oriented and is not in acute distress, but he is holding his left hand with his right hand. His skin color is good, and he is breathing comfortably but slightly faster than normal. His lungs are clear to auscultation. His heart rate and rhythm are regular, without murmur, rub, or gallop. His abdomen has a normal appearance and is soft and nontender, without rigidity, rebound, or guarding.

The patient’s left middle finger is significantly swollen over the distal phalanx, and there is a large subungual hematoma encompassing 80% of the surface of the nail. He reports only minimal pain with palpation over the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. There are no breaks in the skin.

Urgent Care Work-Up

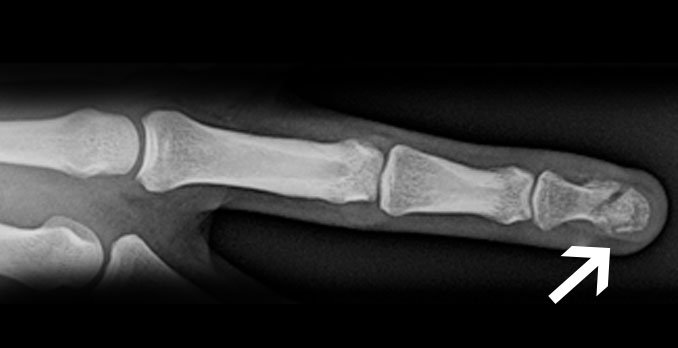

An x-ray is obtained that shows a distal phalanx (tuft) fracture (Figure 2).

Differential Diagnosis

- Mallet finger

- Joint dislocation

- Osteolytic lesion

- Osteomyelitis <

- Subungual hematoma

Learnings

A tuft fracture is the most common finger fracture, accounting for 9.6% of all adult fractures and occurring twice as often in men as in women. These fractures are typically caused by a direct blow to the distal phalanx. They can be accompanied by a subungual hematoma or a laceration, converting these fracture from closed to open.

The finger is composed of the proximal phalanx, middle phalanx, and distal phalanx. The distal phalanx is flexed by the flexor digitorum profundus and extended by the extensor terminal slip. Fractures of the distal phalanx may be isolated to the bone or may extend into the joint. The latter are termed inter-articular fractures.

The most typical mechanism for a tuft fracture is a crush injury, either as direct trauma to the finger (such as a hammer hitting the finger) or as compression trauma (such as the finger getting slammed in a door or crushed with machinery). If a fall was involved, there may be other injuries. Inquire about pain in the hand, wrist, and elbow. Injury may also occur from an axial load or laceration. If there was an altercation, inquire about other injuries, a police report, and the possibility of physical abuse. Assess for neurovascular compromise by asking about numbness or disproportionate pain. Localize the area of greatest pain, typically over the dorsal aspect of the DIP joint, and inquire about what makes the pain worse. Determine the patient’s tetanus status.

Assess for the presence of visible deformity and swelling, and check the integrity of the skin. Look for an open fracture, ecchymosis, or signs of infection if the injury is not acute. In a tuft fracture, there is typically significant swelling at the distal phalanx and often a subungual hematoma. Palpate for pain over the dorsal aspect of the DIP joint as well as the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints for tenderness. Test for strength and range of motion:

- Isolate the DIP joint and assess for strength for flexion and extension. Additionally, assess flexion and extension at the PIP and MCP joints.

- Assess passive ability to extend the finger to check for mallet finger (strain, tear, or avulsion of the extensor tendon connecting the middle phalanx to the distal phalanx dorsally).

- Assess lateral motion. If there is laxity laterally, this may indicate injury to a collateral ligament.

Assess the nail for subungual hematoma or avulsion, and determine the neurovascular status by documenting pulses and/or capillary refill, warmth and normal pink coloration, and sensation

Testing should consist of the following:

- X-rays

- Obtain three views: anteroposterior, oblique, and lateral.

- Assess for fractures:

- Fracture line

- Lucency

- Disruption in trabeculations

- Avulsion fracture

- Intra-articular involvement

- Assess for dislocation.

- Assess for soft-tissue swelling and arthritic changes.

- Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging: These are generally not indicated for diagnosis of an acute, uncomplicated distal phalanx fracture.

These are indications for transferring the patient to an emergency department:

- Visible bone

- Infection (with concern for osteomyelitis in a patient with a longer-term injury)

- Intractable pain

- Concern that a compartment syndrome is present

Treatment

In treating the fracture, start with ice, immobilization, and elevation. If there is a significant subungual hematoma (typically involving >50% of the area), trephinate the nail with an 18-gauge needle or an electric cautery device. Splint the distal phalanx and the DIP joint (while leaving the PIP joint free) for 2 to 3 weeks with a simple finger splint or a stack splint. If there is a finger laceration or subungual hematoma, consider prescribing prophylactic antibiotics to be taken for 3 to 7 days, and arrange for follow-up within 2 to 3 days with an orthopedic surgeon or hand surgeon. Note that the use of antibiotics is controversial: Some studies have shown that antibiotics decreased the rate of infection, but new studies have shown that they made no difference. Most patients with distal phalanx fractures will be treated without surgery. Provide tetanus prophylaxis if the last immunization was given more than 10 years earlier.