Published on

Urgent message: The financial health of your practice depends on a balanced approach that takes into account both increasing income and reducing expenses.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc, Experity

From an economic perspective, the independent urgent care owner/operator has a dual goal: to build the long-term value of the medical practice while maximizing cash that can be taken out of the business in the form of income.

To achieve both of these goals—to expand revenues while reducing costs—both a strong offense and a strong defense are required.

Finding Cash in the Practice

Cash is the lifeblood of any medical practice; it flows in through patient service revenues and flows out through the payment of salaries and expenses. Changing the direction of cash flow can be a difficult undertaking, but it is possible by uncovering the common “hiding places” of cash. These include accounts receivable (AR), accounts payable, inventory, and administrative expenses.

Accounts receivable days, calculated as accounts receivable divided by annual sales times 365, is the traditional benchmark for the effectiveness of cash collectionand consists of both insurance and patient balances. If your practice AR is greater than 45 days and 20% or more consists of patient balances, the answer to accelerating cash flow may be found at your front desk.

How well does your front desk staff understand insurance and medical billing terminology?

Does your front desk staff verify insurance eligibility and collect copays, deductibles, and prior balances from every patient?

And how accurately are they recording patient demographic information, including guarantors and coinsurance? These common shortcomings at the front desk translate to extra work and delays in charge entry, billing, and collections on the back end.

For example, a patient presents a PPO membership card that does not list an urgent care copay. The staff interprets this as “no urgent care copay,” allows the patient to see the doctor, and the claim gets submitted to insurance.

When the Explanation of Benefits is received 20 days later, it turns out that the patient had a $5,000 deductible policy with “no urgent care benefit.” Your billing company invoices the patient without response and only after referring the account to the collections agency—and paying a 25% to 30% commission do you get your cash about six months later.

In effect, you provided the patient with a sizable discount and “no money down, no interest, and no payment financing”—unlike car dealerships and furniture stores that make the same appeal, however, you got no marketing lift from your generosity. Worse, in a certain percentage of cases, patients will never pay the bill, resulting in a write off of the revenue in addition to billing and collections costs.

Had the front desk verified coverage and the presence of a deductible, and understood the difference between “no urgent care copay” and “no urgent care benefit,” the urgent care center could have collected the patient’s financial responsibility at time of service, thus reducing the risk of non-payment and avoiding back-end billing and collections expense.

Although it takes time at registration to contact the insurance company for every patient, doing so is critical to getting paid in today’s fast-changing insurance market.

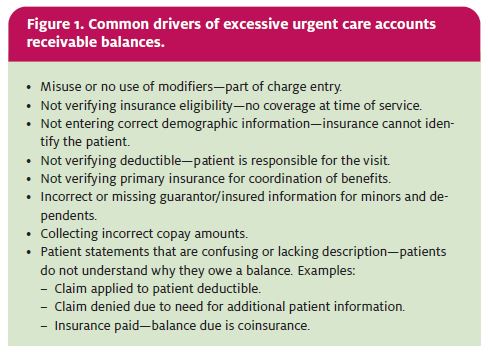

Figure 1 lists the most common reasons why urgent care accounts receivable can grow to excessive levels.

Cash may also be found by improving the efficiency of the back-office billing operation.

Charge entry delays, aging insurance balances and low gross collection ratios may indicate a shortage of billing and collections staff. If you have outgrown your ability to effectively perform billing and collections tasks in-house, evaluate whether new practice management software is in order or if an outsourced billing company can perform more effectively for the same or reduced cost.

Also, sending unpaid patient balances to a collections agency sooner (e.g., after 60 or 90 days instead of 120 days) results in lower commissions and higher collections rates.

Finding Cash in Expense Management

When starting an urgent care practice, physicians often imagine all of the different types of cases that could present at the center and, to be prepared, order a wide range of medical supplies. But supply inventories, including vaccines and injections, can grow to expensive levels when not controlled.

Do you find that a large number of supplies expire before use? Often, supplies are packaged in minimum quantities of 25, 50, or 100 per box, so it’s difficult for a start-up practice to avoid some excess inventory levels. Periodic review of expired supplies may reveal inventory that isn’t needed, however.

Supplies should represent the acuity and frequency of cases that present at the center, as well as the scope of practice.

For example, if the practice treats minors only on a limited basis, there probably isn’t a need to stock a pediatric speculum and intubation kits of various sizes. If standard procedure is to refer high-acuity cases to the emergency room, and squad service is readily available, it may also be unnecessary to stock supplies for critical care or advanced life support.

Vendors are more than willing to present the start- up urgent care with lists of “everything you need to be successful,” but remember that their objective is to sell more medical supplies. For the established practice, negotiating with vendors on a yearly basis can often yield lower prices or more favorable terms, including the ability to return expired/unused items. Existing vendors want to protect their current accounts and competing vendors want to win new business—particularly if they believe a practice is growing. Likewise, group buying organizations can secure lower prices from existing supply vendors by consolidating the demand of many medical practices.

It’s Like Money in the Bank

Banks are hungry for cash, and physician practices flow significant cash through bank services. Banks are also eager to serve doctors, who tend to borrow and invest more than the average customer. Because banks assess the value of relationships in terms of profitability, they are usually willing to negotiate lower interest rates and service charges if they can sell more services, including lines of credit, treasury management, and credit card processing.

Compare the services of different financial institutions and evaluate ways that interest paid on cash balances can offset fees. Treasury management offerings such as sweep accounts, direct deposit, in-office check scanning, and lockbox can accelerate cash deposits of third-party payments.

Online bill pay can improve the management of payables, assuring that a practice takes advantage of vendor discounts for prompt payment, avoids service charges for late payments, and stretches payments to the maximum allowed by the vendor contract.

Almost any expense can be a potential source of cash for your practice. Challenge your staff to constantly identify expenses that can be cut and processes that can be improved sharing some of the savings with staff ups the ante and aligns staff incentives to the practice ownership.

The Best Defense is a Good Offense

While it’s impossible to build a successful medical practice on cost cutting alone, managing costs is al- ways easier than growing top-line revenue. On a typical profit-and-loss statement, there are many lines that describe costs such as labor, rent, and supplies, but all revenue is typically summarized in one or two lines: “urgent care fees, net of adjustments.”

As a result, revenue is the most misunderstood and neglected measure in business. Vague statements such as a “slow flu season,” “unseasonably warm weather,” and “increasing competition,” are often used to explain away revenue that falls short of projection.

Moreover, while expenses are incurred on a day-to- day basis, daily revenues are the culmination of many decisions over time that influence consumer demand and preferences, including location, marketing/branding, and customer servicing and customer service discussion too involved to cover here; instead, let’s concentrate on the two components of charges, which are the fee schedule and physician coding.

Fee Schedules: Leave No Money on the Table

In an ideal world, an urgent care fee schedule would represent what a physician thinks his or her service is worth based on skills and training (including board certifications), office location and hours, and the clientele attracted. But this is just the retail price more important is the discount price offered to third party payors.

All too often, practices just accept whatever fee schedule is sent to them by payors, without negotiating specific volumes or payment terms.

When was the last time you met with a payor to ask what you are receiving in return for the discount you are offering them? Accepting whatever payors offer has become so routine for urgent care centers that the retail fee schedule matters little.

Insurance contracts pay the “higher of contract or billed charges,” so to assure that no money is left on the table, urgent care fee schedules are typically set at 150% to 200% of Medicare fees. In no case should billing be less than the highest paying contract for a particular CPT code. Many ur- gent care centers further discount these fees for cash pay patients.

When negotiating insurance contracts, you should examine the 20% of CPT codes that make up 80% of urgent care revenue by setting up a spreadsheet listing reimbursement by payor and CPT code. This spreadsheet will demonstrate variances between payor and the volume effect on total revenue.

Although a very favorable contract may pay an average 20% premium to Medicare, if the reimburs ment on the most frequently used CPT codes is less than that, the contract could be less “favorable” than you thought.

A $5 to $10 variance on one or two high-volume codes could result in lower revenue—perhaps thousands of dollars per year. Consequently, negotiation should focus on the codes used most frequently in your practice; if you can get a good rate on your top 20%, it may be worthwhile accepting less on the others. (Of course, good reimbursement on a CPT code is only meaningful insofar as the practice codes correctly.)

Provider Chart Review

Physician knowledge of evaluation and management (E/M) coding has a direct impact on the ability to charge accurately for the services provided. If a provider codes visits too low, or does not document visits to justify a higher potential code, then money may be left on the table.

A simple chart review, which can be either retroactive (examining past services) or proactive (before the claim is submitted), can help identify possible loss of revenue and red flags that could invite a letter of requested information from a third-party payor. Chart reviews can be conducted by a certified medical coder in your billing organization, by an outside accounting or consulting firm, or by a physician in the practice skilled in the complexities of medical billing.

The chart review identifies examples of over- and under-coding that affect level of service billing. History, exam, and medical decision making documentation must all support the selected code; when they do not, the practice should bill at the level sup- ported by the documentation, which may result in “lost” revenue if the code billed is less than what actually occurred.

If documentation and coding issues cause one physician to “lose” $10 to $15 in potential revenue per patient, over the course of a year an average urgent care practice would forego more than $100,000 in revenue. When coding and compliance issues are uncovered in the chart review, the solution is education. Urgent care physicians need to have a clear understanding of Medicare reimbursement guidelines and documentation requirements. Chart reviews should be repeated until the physician is compliant.

The process should not be punitive, but rather, focused on helping the physician attain appropriate coding levels. Another solution is to implement an electronic medical records system that includes a coding engine.

Conclusion

Consistently winning in the game of business requires both a calculating offense and a steadfast defense. Success comes from balancing revenue growth against cost savings. Successful urgent care practices constantly evaluate all aspects of their operation to find ways to improve efficiency while also increasing customer satisfaction and quality of care that assure long-term increases in volume.