Published on

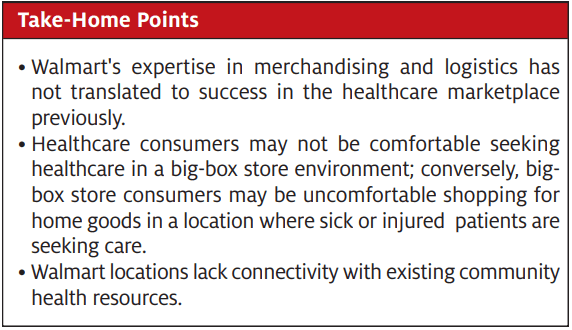

Urgent message: It’s important for urgent care to watch and learn from Walmart, which has engaged leading retail and strategic consultants to develop “Walmart Health.” However, based on Walmart’s three previous failures to penetrate any significant share of even its own stores with a retail clinic model, skepticism over Walmart’s ability to execute as a healthcare provider is warranted.

If Walmart has its way, America’s burgeoning healthcare marketplace is about to get a lot more crowded. The Bentonville, AR-based retail giant, in an ambitious attempt to grab a share of the $1.3 trillion U.S. healthcare market, has recently opened two pilot Walmart Health clinics in the state of Georgia. And unlike its three previous unsuccessful forays into delivering a viable retail clinic product, this latest iteration features a full-fledged, standalone primary care clinic alongside an array of additional health and wellness offerings.

So given Walmart’s deeply entrenched branding, vast financial resources, and formidable retail might, should urgent care be concerned about Walmart as a competitor?

Walmart Health

The launch of Walmart Health is the retail chain’s fourth iteration of its retail clinic model spanning the past 12-15 years. This latest version offers an all-in-one health center that includes the following services:

- Primary care

- Dental

- Vision services

- Hearing services

- Labs (onsite)

- Imaging (onsite)

- Mental health counseling

- Pharmacy

Walmart Health touts its pilot health centers as state-of-the-art facilities, with the appearance of a freestanding building and a separate entrance from the adjacent supercenter. With its array of services under one roof, Walmart Health is advertising itself, according to press releases, as “a supercenter for basic health services.” The new clinics promise transparent, affordable pricing regardless of insurance coverage: a $40 flat fee for a primary care visit, $45 for an appointment with an optometrist, $50 for an adult dental visit, and $1 a minute to see a therapist. Additional health professionals, as well as onsite health insurance educators, will be available to assist patients. Through partnering with local providers, Walmart Health clinics will be staffed with physicians, nurse practitioners, optometrists, dentists, and mental health professionals. In effect, Walmart Health aims to bring a one-stop-shop approach to community healthcare, and leverage its retail expertise towards providing an affordable, accessible, and convenient healthcare experience in a retail setting.

Walmart’s Latest Foray Into Retail Healthcare

Walmart currently operates 19 clinics across Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina, but those are limited in scope as to the services they provide. Walmart Health, on the other hand, with its full-service offering, signals that the retailer is attempting to make a deeper dive into the healthcare business and preparing to employ its considerable resources to do so. Walmart already operates one of the largest pharmacy chains in America, and with the introduction of its two pilot health centers in Dallas and Calhoun, GA, respectively, looks to position itself as a major player in the healthcare game over time.

With an eye on potential profits and the chance to grab a bigger slice of America’s trillion dollar healthcare pie, Walmart figures it can merge its powerful branding with the inherent trust that people place in their doctors, and make Walmart Health a preferred access point with consumers.

Although ambitious, this latest venture will stick to providing basic health services to the 80% or so of people who account for 20% of healthcare expenditures; Walmart Health is not designed to provide longitudinal care for patients who require specialist care or have chronic conditions.

Ultimately, Walmart is banking on its retail know-how to develop a consumer-friendly access point that makes seeking healthcare as simple and straightforward as heading down to the local supercenter to grab a gallon of milk or a loaf of bread. Walmart spokespeople admit that although this latest retail clinic foray is a gamble, it’s a serious strategy to which the company is fully committed. The inherent risks, they reason, are well worth the potential rewards for Walmart’s customers, the communities where Walmart operates, and of course the retailer’s stockholders.

Should Urgent Care Be Concerned?

Urgent care is already facing stiff competition for patients from retail clinics operated by the likes of CVS and Walgreens, freestanding ERs, telemedicine providers, and niche players like ortho and pediatric urgent care. Is Walmart, with its 5,300 U.S. stores and prebuilt infrastructure, now another looming threat? After all, this is its fourth retail clinic iteration, indicating that the world’s largest brick-and-mortar retailer is determined to stake a claim in America’s crowded healthcare space. Walmart already does $36 billion annually in health and wellness sales, and clearly sees the opportunity to increase that revenue.

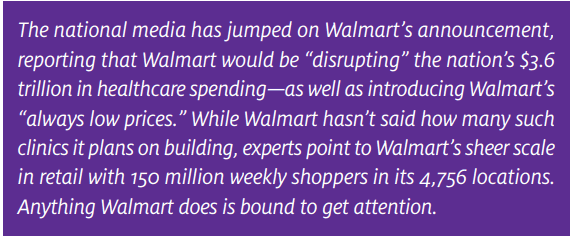

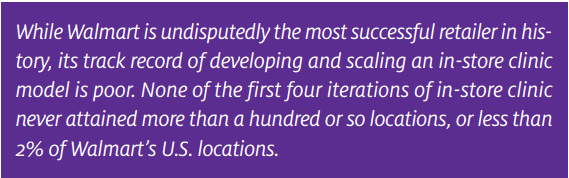

The very fact that Walmart Health is the fourth retail clinic attempt, however, may in and of itself provide important clues as to why Walmart has not been successful thus far, as well as forecast its future prospects of gaining traction in the retail healthcare game. None of the in-store clinic models Walmart has tried over the past 15 years has gained traction in more than a hundred or so locations. Given that Walmart has over 4,700 U.S. stores, a clinic in 2%─3% of locations—between 94 and 141 sites—can hardly be considered a “game changer..” But each time a new model was introduced, the press seemingly forgot about the previous iteration and reported that Walmart was on-course to “change the way healthcare is delivered.”

So the obvious question is: What went wrong with the first three interactions? We’ll briefly examine each iteration in the following sections, along with the primary reasons why they never broadly appealed to consumers.

Iteration 1: Rent Space to Third-Party Clinic Operators

Over a decade ago, Walmart announced that it would be opening health clinics in its stores, which at the time was considered innovative and revolutionary. This first iteration entailed Walmart contracting with independent third parties to operate the clinic in the Walmart store—essentially leasing retail space from Walmart. This model is a pure landlord/tenant relationship which requires the clinic operator to be profitable as a stand-alone business, while Walmart would also gain from increased foot traffic in its stores and sales of prescriptions and OTC meds. Because these third-party clinics in Walmart never attained break-even volumes, and because the clinic itself didn’t benefit from “downstream” retail sales that were going to Walmart…this first iteration quickly failed as the initial entrepreneurs pulled out and/or leases expired.

Walmart managed to open around 100 or so of these clinics, but the iteration was short-lived. After about 2 years when the initial leases on the Walmart retail space began to expire, the third-party operators closed their in-store clinics. Why? Because with the third-party independent operator model, they had to be able to turn a profit at the point of service to be a viable offering. And these clinics never achieved profitable patient volume. This issue was compounded by the fact that all of the “downstream” revenue the clinic generated—for example, the sale of the over-the-counter medication like the $20 Mucinex or the $18 Robitussin, or the filled prescriptions from the pharmacy—was all going to Walmart, and not the independent clinic operator. So as it turned out, this first iteration was not a sustainable model.

Iteration 2: Engage Hospitals and Health Systems

The second iteration had the same economic model as the first—a tenant/landlord relationship with Walmart—but this time the tenant would be hospitals and health systems rather than entrepreneurs. The difference is that a hospital can make a business case for a clinic that loses money at the point of service, so long as either greater costs are avoided elsewhere (eg, in shifting low-acuity Medicaid patients out of the emergency room) or “downstream” revenues are realized in primary care, specialty and facility-based practices through the capture and processing of medical referrals.

The hospitals and health systems were more concerned with building their brand than realizing point-of-sale profits. They would attract patients into the clinic, and then refer those patients to the hospital’s facilities, specialist, and primary care providers—in other words, downstream revenue. The clinics would also serve to ease the burden placed on the hospital’s emergency department by Medicaid patients who were crowding the ED. And again, the Walmart store would benefit from all the OTC and pharmacy sales generated by the clinic.

With this second clinic iteration, a couple of the more successful health systems with Walmart tenancy created consulting businesses to help other health systems replicate their Walmart “success,” although in the end, no more than a hundred or so locations opened. Even when a health system creates a business case for a physical “brand presence” in Walmart—one in which margin will be realized elsewhere—long-term, hospitals still have little tolerance for low patient volumes.

After a couple of years of this model, which never got to more than 100 or so locations, the clinics again began to close. The culprit was a lack of patient volume in the Walmart store, same as before.

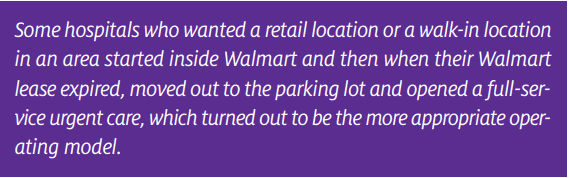

A helpful anecdote underscores the root issue: we know of a couple of hospitals that desired a walk-in clinic in a retail area, opened up in Walmart under the second iteration clinic model, and when the Walmart lease was up, opened a full-service urgent care basically in the parking lot. Interestingly, this turned out to be a more viable and appropriate model than the Walmart in-store clinic.

Perhaps one problem is that Iterations 1 and 2 were both “retail clinics” from the standpoint they were staffed by nurse practitioners with a predefined set of services and prices, limitations in the scope of care due to the clinic’s physical set-up and capabilities, and also limitations on the nurse practitioner’s scope of licensure. Retail clinics diagnose and treat the most basic of medical concerns like pink eye and sore throat, lack x-ray and any substantive laboratory testing required for diagnosing more complex conditions including pneumonia, and also lack a sanitary table and lighting to perform procedures like laceration repair and abscess drainage. The clinics also could not treat workers’ compensation injuries. Mostly retail clinics are effective at administering vaccines including flu shots, which can also be done directly from the pharmacy. The issue with limited services is that retail clinics address only a very small portion of the total market, compared with the full scope of services offered in more conventional urgent care settings. T

Retail clinics are also a very seasonal business and “flu epidemics” are unpredictable. Treating low-level conditions—like those associated with seasonal cold, flu or allergy symptoms—results in a more extreme seasonality of patient visits than a full-service urgent care that can treat a range of patient conditions year-round. The seasonal nature of limited scope care leads to complications in recruiting and staffing the clinic, which is exacerbated by high turnover of nurse practitioners who can become bored working by themselves and within only a very narrow range of their training.

When the services of a retail clinic are too limited to be practical, that clinic becomes an excellent referral source to urgent care as opposed to being urgent care’s direct competition.

Iteration 3: Walmart Would Operate the Clinic Itself

Even after two previous unsuccessful forays, Walmart’s determination to have some form of in-store retail clinic never wavered. So for its third iteration Walmart itself would own and operate the clinics. Only this time, the clinics would primarily serve Walmart employees.

The third iteration saw some major operational improvements such as greater square footage, an exterior entrance into the clinic from the parking lot, and an expanded scope of services including primary care, immunizations, and lab testing. Most significant is that Walmart, rather than an entrepreneurial or hospital operator, would operate the clinic itself, including employing the providers. The strategy behind the way this iteration can be illustrated by examining the Dallas/Ft. Worth, TX market, where Walmart opened its initial third iteration clinic.

In North Dallas, there are over 20 Walmart supercenters, with each store having 350-500 employees. The pilot third iteration clinic was opened in Carrollton, TX. Based on the 20 or so centers in this market, Walmart would have around 10,000 employees within a 15─20- minute drive. By opening a clinic that would primarily serve Walmart employees, the retailer had in effect created an employee near-site, or an onsite clinic that would also serve the general public by offering $40 cash paid visits. Once again, though, this clinic iteration stalled out, having never even reached 20 locations. And judging by the fact that the only insurance accepted by the clinic is the Walmart health plan, United HealthCare, and Medicare, the major insurance payers were never really onboard with the concept.

Walmart’s Foray as an EMR Vendor

So, three total launches over a 12-year period, all receiving “game-changing” media coverage, and not one gained significant traction. Also noteworthy is the fact that Walmart retail health clinics have not been the retailer’s only unsuccessful attempt at carving out a real niche in the healthcare market. Back in 2009, Walmart-owned Sam’s Club, eClinicalWorks and Dell announced that they would be partnering to develop a turnkey electronic medical record and practice management solution geared toward small physician practices. As cost and complexity had remained a significant barrier to entry for small practices with limited capital, this cost-effective EMR package was touted as a game-changer that would have a profound effect on the market. Based on press releases at the time, this package was guaranteed to increase adoption rates which would improve patient care.

Not all the press this Walmart-spearheaded collaboration received was positive. Many prominent industry voices sounded warning alarms, as there was widespread concern and skepticism about whether Walmart had the expertise and competence to develop a product that would securely safeguard patient privacy, and whether a retailer could properly handle having access to such sensitive medical information and patient data. These questions went unanswered, as the entire venture abruptly went away, with no warning or real explanation as to why.

Walmart’s Strength Is in Procurement and Logistics—Not Operating Healthcare Facilities

Walmart’s strength has always been in its procurement and logistics. In order to fulfill its promise of “always low prices” to consumers, Walmart scours the globe for the best prices, which it brings to its stores through the industry’s most sophisticated logistics and transportation system. In fact, Walmart has been called a “logistics company” not a retailer and its long-term value (in rural America especially) is to be an outlet for any product that can be procured on the internet. Walmart has been called the “Amazon of rural America” for this reason.

Walmart’s strength in procurement applies not only to the products it sells, but also to services for its 1.5-million-plus U.S. employees. Walmart is the largest private sector employer that is also self-insured for its employee health plans. To assure high-quality medical outcomes for the lowest price, Walmart has created relationships with leading academic medical centers like the Cleveland Clinic (for cardiac care), Mayo Clinic (for cancer care and transplants), Johns Hopkins (for joint replacements) and Geisinger (for weight loss surgery). Walmart procures excess capacity from, or assures a minimum level of revenue to, these medical centers and in exchange gets significant discounts for treating its employees. By picking the “best of the best,” Walmart also assures strong clinical outcomes—supported by data—which saves money over time by avoiding complications and re-admissions. Walmart employees who take advantage of these “Centers of Excellence” do so with company-paid travel and all out-of-pocket responsibility waived.

Likewise, on a local level, Walmart steers employees to prescreened physicians in specialties like primary care, cardiology, and obstetrics, whom its data say deliver the highest quality for the lowest price. Primary care copays are capped at $35 to assure employees seek care early, before a minor problem evolves into something more serious (and costly) to treat. Walmart has even added healthcare “concierges” to help its employees navigate their community’s health resources. Employees with more complicated histories may also be assigned to a “personal online doctor” who helps manage chronic conditions and coordinates specialty care when needed.

Using hard data to negotiate the best prices and clinical outcomes for its employees at the most reputable medical centers nationally seems far more in-line with Walmart’s retail procurement and logistics excellence. But despite this success in procurement and logistics, Walmart has never demonstrated its success as a healthcare operator (or provider of any other service, for that matter).

Walmart Heath Faces Obstacles

Can Walmart’s fourth retail clinic iteration succeed where the first three failed? Based on their enthusiastic pronouncements, the retailer’s execs and spokespeople firmly believe so. Although innovation in healthcare is risky and difficult to pull off generally, Walmart is aiming to prove that their brand of retail healthcare specifically—infused with their retail expertise and Infrastructure—will appeal to consumers in a big way. And while this latest launch has been accompanied by the same ample media coverage as the first three iterations, it’s being regarded with an equally healthy dose of skepticism from healthcare academies and other experts in the field. While they loved Walmart’s ambition, there seems to be a general consensus that Walmart Health will have to overcome the following obstacles to really take off:

- Walmart’s store slogan is, “Low prices. Always.” And they’re synonymous with that guarantee. Research shows, however, that when it comes to healthcare, people are more interested in quality than rock bottom prices. So where Walmart’s low price mantra helps them sell consumer goods, if people associated Walmart Health with ideas like “bargain” and “discount” it may lend to the perception that Walmart Health services are of inferior quality compared with their healthcare-focused competitors.

- Trust in this case overlaps with branding that has worked in healthcare with established health systems. The Mayo Clinic, for example, is renowned nationwide and associated with the best doctors, specialists, and facilities. So the experts rightly wonder aloud whether a big-box retailer can even achieve that level of trust with consumers. This may have been the downfall of the first three Walmart clinic iterations, and remains a significant obstacle for Walmart Health.

Beyond the brand, trust goes to much more than the name on the front of the building. People place implicit trust in their personal physicians first, and the facility second. For most patients, their relationship with their doctor matters more the medication or the procedure. So if a Walmart physician leaves the store, will the patients follow? And, while mental health counseling likely won’t account for a significant amount of patient volume, will people really trust what they regard as a Walmart employee with their most intimate mental health issues?

Can Walmart Change Consumer Behavior?

Perhaps the greatest elephant in the room when discussing Walmart and healthcare is whether it’s “consumer behavior” to seek care in a Walmart store. Ask some consumers and they will say that Walmart is cluttered, dirty, crowded, or simply too large to comfortably navigate. In many communities, Walmart is the epicenter of the area’s crime rate. If Walmart is going to be in the healthcare business, there’s also concern when not ill about frequenting a store that attracts sick and contagious people.

The public is used to getting healthcare in traditional ways—going to a hospital or related facility, doctor’s office or urgent care center—so to be successful, Walmart must change the entire way people view and receive healthcare. This acceptance factor of Walmart as a healthcare brand creates a significant barrier out of the gate that isn’t necessarily present with more traditional healthcare delivery channels.

Healthcare diversifies Walmart’s revenue away from merchandising, especially as Walmart now competes online, where internet retailers aren’t burdened with Walmart’s brick-and-mortar costs. The ability to drive revenue in the winter months when (post-Christmas) retail sales are typically their slowest, could complement Walmart’s total corporate cash flow. Healthcare is also historically exempt from recession and other economic pressures that adversely affect retail sales. So, not only does healthcare represent a multibillion revenue growth opportunity for Walmart, it can also have a “smoothing effect” on Walmart’s financial performance.

And last, a big problem is there is little to no connectivity of Walmart Health with the community’s health resources (vs, say, an urgent care that is affiliated with and shares the same electronic medical record with a local or regional hospital or health system). Many of Walmart’s employees and customers suffer from comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, and COPD that need to be managed in a primary care medical home, where the patient can be referred to various specialists as needed. By contrast, Walmart’s approach is more transactional, focused on selling single visits and one-off services from a “menu,” than on providing a continuum of care.

Walmart Is Not a Threat to Urgent Care

Walmart has embarked upon four iterations of its retail clinic model over the past 12-15 years. Given that Walmart has over 5,300 stores, and not one of these iterations has reached more that 100 or so locations, the logical conclusion is that consumers simply don’t seek urgent care in Walmart. The retailer has undoubtedly learned valuable lessons from its first three iterations that it can apply to Walmart Health. But people are accustomed to receiving healthcare from traditional providers in traditional settings. For Walmart to be successful, they would have to change the entire way people view and receive healthcare, which has proven a tall task so far.

What Walmart has proven highly successful at is global procurement. They expertly and efficiently build scale in purchasing to secure the lowest prices, which includes, ironically, innovative approaches to purchasing healthcare for its own 1.5 million employees. But the retail powerhouse has yet to demonstrate competency as a healthcare operator or in delivering healthcare services.

Conclusion

Walmart is undisputedly the world’s most successful retailer, driven by its deep expertise in procurement and logistics. When this expertise is applied to healthcare, Walmart has created an innovative and cost-efficient benefits program for its own employees producing remarkable clinical outcomes. But as a “merchandiser” of goods—and specifically a provider of services—Walmart has a dismal track record in scaling a viable clinic concept. Urgent care should therefore watch this newest iteration of “Walmart Health” with skepticism while also learning what it can from the world-class expertise Walmart has put behind the project.