Published on

Urgent message: Urgent care centers must dispose of fully depreciated office equipment such as computers, copiers, fax machines, and telephones containing protected health information in a manner that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. How this column helps you: gives you guidelines for protecting your patients’ privacy.

Introduction

Since 2009, 42 million patients have been affected by privacy breaches entailing their protected health information (PHI).1 Many of these breaches stem from the improper disposal of fully depreciated office equipment that may retain digital PHI in its memory. Realizing that disposing of this equipment poses risks of fines and damage to their practice’s reputation, but not having a plan in place to dispose of equipment properly, many urgent care operators simply let old equipment accumulate in their storage closets. This practice not only creates unsightly clutter but introduces risk of theft and future breach or damage from fire or water, because this old equipment is rarely inventoried and tracked over time. Worse yet, some centers donate, sell, or re-purpose equipment without taking the proper steps to remove its digital PHI. A better practice is for urgent care centers to devise a plan and dispose of equipment in a manner that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) as soon as it is removed from service in the business.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule

HIPAA’s Privacy Rule created national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other PHI. This rule from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) applies to health-care providers who conduct certain health-care transactions electronically. The Privacy Rule requires urgent care centers to implement appropriate safeguards to protect the privacy of PHI, including its disposal.2

In addition, the HIPAA Security Rule mandates that covered entities implement policies and procedures to address the final disposition of electronic PHI, as well as the hardware or electronic media upon which it is stored. In the same light, covered entities must implement procedures for removal of electronic PHI from electronic media before the media is made available for reuse.3 Finally, covered entities must provide their staff with training and then make sure staff members follow the disposal policies and procedures.4 HHS states that any staff member (including volunteers) who is involved in disposing of PHI—or who supervises those who dispose of PHI—must receive training on its proper disposal.5

The PHI on a computer, copier, or cell phone can be disposed by destroying the entire piece of equipment or by destroying just the digital medical information stored on it and then reusing the equipment. The touchstone for these criteria is “reasonable safeguards,” because the HHS does not provide precise parameters but instead states that appropriate safeguards are based on the specific circumstances of the covered entity.

Physical Safeguards for Disposal

The Security Rule defines physical safeguards as “physical measures, policies, and procedures to protect a covered entity’s electronic information systems and related buildings and equipment, from natural and environmental hazards, and unauthorized intrusion.” This standard covers the proper handling of electronic media, including receipt, removal, backup, storage, reuse, disposal, and accountability. In this context, electronic media means “electronic storage media including memory devices in computers (hard drives) and any removable/transportable digital memory medium, such as magnetic tape or disk, optical disk, or digital memory card . . .” Any PHI that an urgent care center stores on a computer, computer system, or remote drive will be included in this definition.6 This includes laptop computers, computer workstations and servers, copiers, digital scanners, fax machines, digital cameras (including SD [secure digital] cards for data storage), cell phones, tablets, phone systems, laboratory and x-ray clinical equipment, and electronic media (disks, CDs, microfilm).

Disposal Methods

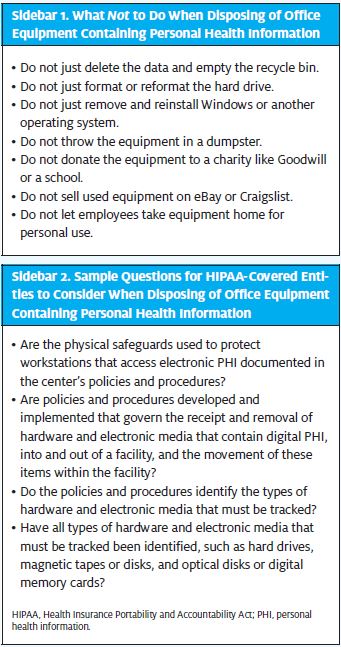

Although the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule do not require or endorse a particular disposal method, an urgent care center obviously cannot just abandon PHI or dispose of it in the trash (Sidebar 1), which may be accessed by unauthorized persons. The HHS advises covered entities such as urgent care centers to review their own circumstances to determine what steps are “reasonable to safeguard PHI through disposal,”6 and to develop and implement those policies and procedures necessary to carry out those steps (Sidebar 2).

However, it appears that in judging what is reasonable, HHS will look at whether the urgent care center thoroughly assessed the potential risks to patient privacy and took into account issues such as the form, type, and amount of PHI to be disposed. Adherence to the urgent care center’s written policies, along with thorough documentation of the process and actions taken, should go a long way to satisfying the letter and spirit of the law contained in the HIPAA Privacy Rule and Security Rule. When covered entities dispose of any electronic media that contains electronic PHI, HHS guidelines are they should make sure it is “unusable and/or inaccessible.”

However, it appears that in judging what is reasonable, HHS will look at whether the urgent care center thoroughly assessed the potential risks to patient privacy and took into account issues such as the form, type, and amount of PHI to be disposed. Adherence to the urgent care center’s written policies, along with thorough documentation of the process and actions taken, should go a long way to satisfying the letter and spirit of the law contained in the HIPAA Privacy Rule and Security Rule. When covered entities dispose of any electronic media that contains electronic PHI, HHS guidelines are they should make sure it is “unusable and/or inaccessible.”

Covered entities are encouraged to consider the steps “that other prudent health care and health information professionals are taking to protect patient privacy in connection with record disposal.”7 This indicates that there is somewhat of an industry standard to be followed, or that HHS is leaving the details of appropriate disposal to the urgent care centers and other covered entities themselves to determine what is sufficient.

Depending on the circumstances, proper disposal methods for electronic PHI at an urgent care center may include (but are not limited to) clearing, purging, or destroying the media.

- Clearing: This entails using software or hardware tools to overwrite digital media with non-PHI-sensitive data. Disk-wiping software will completely erase the information, overwriting each individual sector on a hard drive multiple times to erase the data from the entire hard drive. Microsoft suggests KillDisk8 or DP WIPE,9 both of which are free and designed to meet government standards.10

- Purging: This is degaussing or exposing the media to a strong magnetic field to disrupt the recorded magnetic domains. Degaussing will totally erase the data.

- Destroying: Without a doubt, physically destroying a hard drive is by far the most effective method to ensure safe disposal of PHI. This can be via disintegration, pulverization, melting, incinerating, or shredding. One can smash a hard drive with a sledgehammer, drill holes into the drive, tear the drive apart and destroy the platters, or shred the drive—any of which will make the data inaccessible.11

The most careful approach is to use more than one or all three of these procedures (clearing, purging, and destroying) when practical. If a drive is wiped, degaussed, and destroyed, recovering the data is near to impossible.11

Disposal by a Business Associate

The HHS rules state that a covered entity is permitted (but is not required) to hire a contractor to appropriately dispose of its PHI. Under HIPAA, contractors who deal with PHI are considered business associates who must demonstrate their own compliance with the Privacy Rule and Security Rule. If an urgent care facility uses a contractor, it must sign a contract stating that the business associate, among other things, will appropriately safeguard the PHI through disposal.12 For example, an urgent care owner may hire an outside vendor to pick up PHI on electronic media from its facility, purge or destroy the electronic media, and throw the deconstructed material in a landfill.

Fines and Penalties

Failing to implement reasonable safeguards to protect PHI when disposing of equipment can result in fines and penalties to the urgent care center. Discarding PHI without its destruction is a violation that qualifies for the highest level of HIPAA fines. Penalties can range from $50,000 to $1,500,000 per incident, and the fines are between $10,000 and $50,000 per record when the HHS determines that unsecure disposal of computers is the result of inadequate policies or training.13 In addition, state attorneys general have the authority for state-level enforcement of HIPAA and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, and these offices are allowed to keep any of the fines they assess.14

Conclusion

In effect, equipment with PHI may be thrown in a dumpster—but only if the PHI has been made unreadable, indecipherable, and unreconstructable before being thrown in the trash. Your urgent care center must to take the steps necessary to create and implement the disposal policies, procedures, and training to comply with HIPAA regulations, and ensure that these safeguards are reasonable for your center’s circumstances.

References

- McCann E. Biggest HIPAA breaches of 2014. Healthcare IT News. 2014 December 26. Available from: http://www.healthcareitnews.com/slideshow/biggest-hipaa-breaches-2014

- S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. Health information privacy. Washington DC: U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services [published 2009 February 18; accessed 2015 May 15]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/580/does-hipaa-require-covered-entities-to-keep-medical-records-for-any-period/index.html

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45, part 164.310 (Physical safeguards), (d)(2)(i) and (ii). Washington DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office. Available from: http://www.ecfr.gov

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45, part 164.306 (Security standards: general rules), (a)(4); part 164.308 (Administrative safeguards), (a)(5); and part 164.530 (Administrative requirements), (b) and (i). Washington DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office. Available from: http://www.ecfr.gov

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45, part 160.103 (Definitions). Washington DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office. Available from: http://www.ecfr.gov

- S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. HIPAA Security Series, vol. 2, paper 3, p. 10. Washington DC: U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services [published 2005 February; revised 2007 March; accessed 2015 May 15). Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/physsafeguards.pdf. [The security series of papers provide guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on the rule titled “Security Standards for the Protection of Electronic Protected Health Information,” found at Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, part 160 and part 164, subparts A and C.]

- S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. Health information privacy. Frequently asked questions: What do the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules require of covered entities when they dispose of protected health information? Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [published 2009 February 18; accessed 2015 May 16]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/faq/safeguards/575.html

- KillDisk [software]. Mississauga, Ontario, Canada: LSoft Technologies Inc. Available from: http://www.killdisk.com/eraser.htm

- DP WIPE [software]. Bucharest, Romania: Softpedia. Available from: http://www.softpedia.com/get/Security/Security-Related/DP-WIPER.shtml

- Microsoft Safety & Security Center. How to more safely dispose of computers and other devices. Redmond, WA: Microsoft [accessed 2016 August 14]. Available from: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/safety/online-privacy/safely-dispose-computers-and-devices.aspx

- Hasting M. Deleting hard drive data vs. physically destroying hard drive. PC Hell [original accessed 2015 May 16; found now only via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20160206071034/http://pchell.com/hardware/destroyingdataonaharddrive.shtml

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45, part 164. 308 (Administrative safeguards), (b); part 164.314 (Organizational requirements), (a); part 164.502 (Uses and disclosures of protected health information: general rules), (e); and part 164.504 (Uses and disclosures: organizational requirements), (e). Washington DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office. Available from: http://www.ecfr.gov

- Office of the Federal Register and U.S. Government Printing Office. HIPAA administrative simplification: enforcement. Federal Register. 2009 October 30;74(209):56123. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/enforcementrule/enfifr.pdf

- S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. HIPAA: Compliance enforcement: State attorneys general. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [accessed 2015 May 16]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/sag/index.html