Differential Diagnosis

- ST-Elevation MI (STEMI)

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) with strain

- Hyperkalemia

- Left bundle branch block (LBBB)

- Ventricular tachycardia

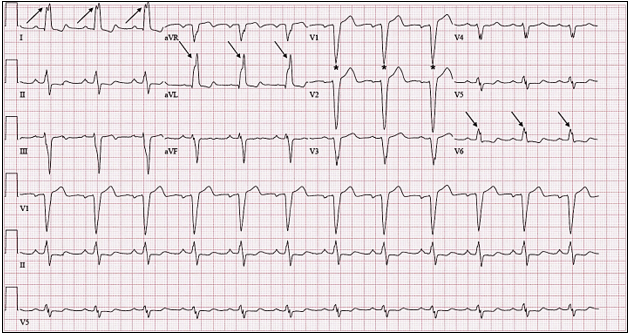

Figure 2. The wide QRS (>120 msec), dominant S wave in V1 (asterisks), broad notched R wave in the lateral leads (arrows) and absent q waves in lead I, V5, and V6 indicates the presence of a left bundle branch block.

Diagnosis

This patient was diagnosed with left bundle branch block.

The ECG reveals a regular, wide-complex, sinus rhythm at a rate of 75 beats per minute. The wide QRS complex (>120 msec), dominant S wave in V1, broad-notched R wave in the lateral leads (I, aVL, V6), and left axis deviation indicates the presence of an LBBB.

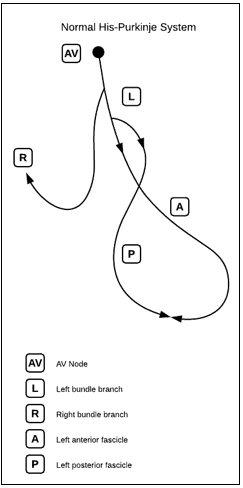

Our current conceptual understanding of the trifascicular framework of the intraventricular conduction system derives from a series of seminal papers by Rosenbaum, et al from 1969 to 1973. These works elucidated three conduction terminals—one in the right ventricle (the right bundle) and two in the left ventricle (the anterior and posterior divisions of the left bundle) (Figure 3).1-3 Conduction disturbances of any or all three conduction terminals may result from structural abnormalities of the His-Purkinje system caused by necrosis, fibrosis, calcification, infiltrative disease, electrolyte disturbances, or impaired vascular supply.4 When conduction is impaired to both left ventricular terminals, the result is an LBBB. Electrocardiographically, the presence of an LBBB can be established via the criteria listed in Table 1.

| Table 1. Abbreviated electrocardiographic criterial for complete LBBB4 |

| QRS duration ≥120 msec in adults |

| Broad notched or slurred R wave in leads I, aVL, V5, and V6 |

| Absent q waves in leads I, V5, and V6, but in the lead aVL, a narrow q wave may be present in the absence of myocardial pathology |

| R peak time >60 msec in leads V5 and V6 but normal in leads V1, V2, and V3 |

| Associated features: ST and T waves usually opposite in direction to QRS Left axis deviation |

Figure 3. The Normal His-Purkinje Conduction System

Image used with permission from ddxof.com

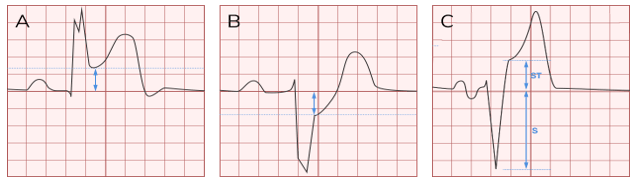

Historically, LBBB was thought to prevent accurate recognition of acute myocardial infarction, resulting in poor allocation of reperfusion therapy.5 In fact, for many years (until 2013), new or presumed new LBBB was considered equivalent to an ST-elevation myocardial infarction.6 We are now able to utilize the Sgarbossa/Modified Sgarbossa criteria to help identify underlying myocardial infarction in patients with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome and an LBBB (Table 2, Figure 4).

| Table 2. Modified Sgarbossa criteria for determining myocardial infarction in the presence of a LBBB.7 |

| ST-segment elevation ≥1 mm and concordant with the QRS in at least 1 lead |

| ST-segment depression ≥1 mm in any of leads V1–V3 |

| Excessively discordant ST-segment elevation in any one lead Defined by most negative ratio of ST/S and at least 1 mm of STE Cut point for ST/S ratio < -0.25 |

Note that the presence of any one of the three criteria rules in for myocardial infarction.

Figure 4. Panel A shows concordant ST-segment elevation. Panel B shows concordant ST-segement depression in leads V1, V2, or V3. Panel C shows excessively discordant ST-segment elevation. Images used with permission from ddxof.com.

The patient in our scenario does not meet any Sgarbossa criteria, nor does the clinical presentation suggest acute coronary syndrome. She has a LBBB, which indicates significant conduction disease, but urgent action is not indicated, and this patient is appropriate for outpatient referral to a cardiologist.

Learnings/What to Look for

- Electrocardiographic findings of LBBB include a wide QRS and a notched or slurred R wave in leads I, aVL, V5, and V6 (see Table 1 for additional criteria)

- Apply Sgarbossa/modified Sgarbossa criteria in patients with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome with LBBB

- Always compare with prior ECGs

Pearls for Initial Management and Considerations for Transfer

- Acutely symptomatic patients with symptoms concerning for acute coronary syndrome should be transferred to an emergency department immediately for evaluation

- A new LBBB in and of itself does not indicate the need for emergent reperfusion; however, the provider must always consider the entire clinical picture

References

- Rosenbaum MB. The hemiblocks: diagnostic criteria and clinical significance. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1970;39(12):141-146.

- Rosenbaum MB, Elizari MV, Lazzari JO, et al. Intraventricular trifascicular blocks. Review of the literature and classification. Am Heart J. 1969;78(4):450-459.

- Elizari MV, Acunzo RS, Ferreiro M. Hemiblocks revisited. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1154-1163.

- Surawicz B, Childers R, Deal BJ, Gettes LS. AHA/ACCF/HRS Recommendations for the Standardization and Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram. Part III: Intraventricular Conduction Disturbances A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009.

- Cai Q, Mehta N, Sgarbossa EB, et al. The left bundle-branch block puzzle in the 2013 ST-elevation myocardial infarction guideline: from falsely declaring emergency to denying reperfusion in a high-risk population. Are the Sgarbossa criteria ready for prime time? Am Heart J. 2013;166(3):409-413.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction – Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). Circulation. 2004;110(5):588-636.

- Meyers HP, Limkakeng AT, Jaffa EJ, et al. Validation of the modified Sgarbossa criteria for acute coronary occlusion in the setting of left bundle branch block: a retrospective case-control study. Am Heart J. 2015;170(6):1255-1264.

Acknowledgment: Images and case provided by Jonathan A. Giordano, DO, MS.