Urgent message: Attracting and retaining urgent care patients entails more than reducing the total duration of patient waits. It also requires understanding and managing patient expectations and perceptions of waiting.

MICHAEL BURKE, MBA, and GARRETT BOMBA, MD

People often respond irrationally in waiting situations. How else can we explain the fact that people are routinely more satisfied with a clearly explained 30-minute wait than with an uncertain 20-minute wait? It is not rational, but it is how we are wired as human beings to respond. Reaction to the experience of waiting—while on hold trying to schedule an appointment, in line at the grocery store, or sitting in the waiting room—is defined less by the overall length of the wait and more by the psychology of waiting. To create the sort of experience that attracts and retains patients, urgent care operators must look at the source of patient expectations and perceptions about waiting rather than focusing solely on reducing its duration.

There has been quite a bit of important research on this topic:

- In 1985, operations expert David Maister, formerly of Harvard Business School, articulated a simple formula to explain satisfaction with the wait experience, S = P – E (satisfaction = perception minus expectation), and proposed a model for the psychology of waiting1 that would be later validated by the research of others.

- In 2002, Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his groundbreaking work in behavioral economics, a science that shows the limits of the assumption of rational behavior. Kahneman and Amos Tversky uncovered cognitive biases that explain quite a bit about perceptions and behavior in waiting situations.2

- Richard Larson from Massachusetts Institute of Technology noted that “the real problem isn’t just the duration of a delay. It’s how you experience that duration.” 3,4

- In health care, researchers have established a clear link among perceived wait times, level of service, and satisfaction.5 This link affects more than just satisfaction with the wait; it colors the patient’s entire experience with the urgent care center.6

What Does the Research Tell Us?

We now know quite a bit about what sets people off when it comes to waiting, and how to transform the experience of waiting into a competitive advantage. First, here are a few items from Maister’s work that illustrate what urgent care patients really hate about waiting:

- Waits of an uncertain duration: The perceived opportunity cost of an open-ended wait triggers loss aversion. Human beings respond about twice as strongly to the possibility of loss as they do to the possibility of gain. That is why an uncertain wait artificially magnifies the stress of waiting more than it should, and more than we would otherwise expect. It is also why Disney always lets you know how long you will wait in line.

- Waits perceived as unfair: Waits with no visible order, such as waiting for a subway train, can create tremendous anxiety. However, that is nothing compared with the reaction when there is a visible order but that order appears to have been violated. Think about your own reaction when someone cuts in line. Even if they cut in line behind you, it is still upsetting.

- Unexplained waits: If an emergency requires the reordering and delay of patients’ visits, explaining this to patients fundamentally changes the context of the situation. When patients hear “emergency,” their context and their expectations immediately shift—usually to a much more tolerant and understanding perspective.

- Unoccupied time: The classic example is the Houston airport that received complaints about the wait at baggage claim.7 The airport decreased the wait time, but complaints persisted. Finally, they decided to increase the distance between the arrival gates and baggage claim. When passengers arrived at baggage claim after the long walk, their luggage was ready, and complaints vanished. By the way, a television in the lobby showing Judge Judy reruns does not qualify as occupied time. Letting patients wait at home or go get a cup of coffee nearby does.

Larson expands on the dangers of unoccupied time. He points to Disney as experts in occupying the time of guests waiting for rides. However, it is much more difficult to make your waiting room an engaging environment than it is to simply let your patients wait somewhere else.

Larson also notes that people generally overestimate the time they spend waiting. To address this, give customers easily accessible, realistic estimates of wait time. This greatly improves the accuracy of the customers’ own guesses at how long they actually waited, and it subsequently has a positive effect on satisfaction levels.

Kahneman and Tversky note that many cognitive biases are rooted in an overall bias for negativity. That is, humans are wired by evolution to respond more strongly to a threat than to a positive experience. A negativity bias is useful if you are trying to avoid a saber-toothed tiger, but in modern life it often creates unnecessary discomfort. That is why the amount of frustration we experience when the line moves slower than expected is much greater than the amount of pleasure we feel if we are lucky to choose the fast line.

Kahneman and Tversky also noticed that the final moments of a waiting situation make the most meaningful impression. If the wait ends positively, as when a health-care provider sees the patient earlier than expected, patient satisfaction goes up. Disney leverages this by overestimating wait times for their attractions so that customers are pleasantly surprised when they wait less than expected. If you do not have a reliable system to keep track of lobby waits, setting accurate expectations can be difficult to do.

People are sensitive to the value of the thing they are waiting on. In environments where patients have options among urgent care centers, perceived value can increase with the popularity of a center.8 The higher the perceived value, the more the customer will be willing to wait. However, once the part of the visit perceived as valuable—usually the time with the health-care provider—is over, patients may have less tolerance for paperwork, for waiting on a prescription, or for waiting for an extended discharge procedure.

In waiting situations of identical durations, people prefer a shorter but slower-moving line to a longer but quicker-moving one.9 This is just one more example of irrationality with waiting. In traditional economic theory, we should be neutral to the two options, but in practice we are not. On the surface, this appears to conflict with the idea that busy centers may have higher perceived value, but it does not have to. The busy center just must make sure to offer patients options other than sitting in the waiting room.

Results

Pentucket Medical is a multispecialty group with more than 50 health-care providers that is part of the Partners HealthCare System. Its two area ExpressCare clinics implemented a wait-management virtual-queuing system to address the following challenges:

- Inability to directly measure wait times

- Incorrect estimation of wait times by front-desk staff

- Patients unable to manage their own wait experience

- Day-to-day fluctuations in wait times

- Inability to balance the load between two area facilities

Features of the system include the following:

- Wait-at-home patients sign in online (Figure 1), choose a time to come in, then arrive when notified.

- Walk-in patients can provide a mobile phone number, and then leave and come back when notified.

- Patients are notified in real time about their specific wait times by text message.

- A lobby television screen (Figure 2) shows the order of patients who are waiting, the estimated wait time, and online versus walk-in status.

- There is a tracking board in the nurse area.

- A post-visit survey is delivered by texting.

- Patients can view wait-time options across facilities and choose the best option on the basis of proximity and wait.

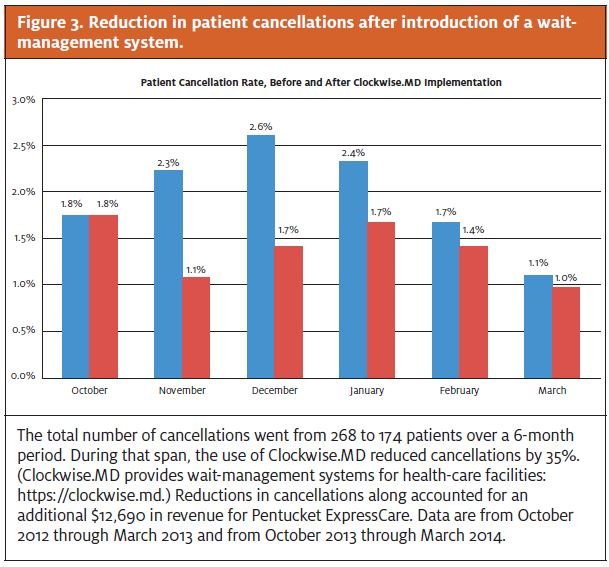

One measure of satisfaction with wait times that Pentucket monitored was the number of patients who decide to leave before being seen. After introducing the wait management system, Pentucket saw a 35% decrease in cancellations (patients who decided not to wait). This reduction accounted for more than $25,000 in additional revenue (Figure 3).

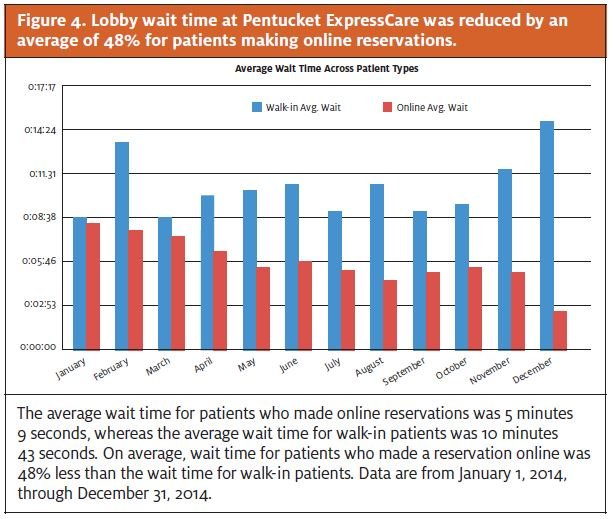

Pentucket managers also noticed that time spent in the lobby was reduced by 48% for patients who made an online reservation (Figure 4).

Post-visit text-delivered patient surveys documented an average satisfaction score of 9.5 out of 10. Ninety percent of patients using online sign in indicated that the ability to make a reservation influenced their decision to use Pentucket Medical.

Table 1 summarizes recommendations for several aspects of wait management. If you are offering reservations (similar to call-ahead seating at a restaurant), then creating appropriate expectations is critical. Do patients think they are creating an appointment or a flexible reservation, or do they think that they are simply joining a first-in, first-out line? Communication in this context is important. If someone believes that they have an appointment, they will be happy to wait up to the appointment time, but any time spent waiting after the perceived appointment can quickly become intolerable.

Table 1. Recommendations for Wait Management |

|

Managing perceptions about wait is an important topic that applies not just to busy urgent care centers. For many patients, especially millennials (people born between 1980 and 2000), patient perceptions start forming early in the process, well before they have shown up at your center. It may begin with your website, or a mobile application, or an online review site.11 If your competitors are skilled at managing waiting psychology, then you must be proactive to ensure the appropriate initial impression, even if your center is new and has low volume. If patients believe they have some measure of control over the waiting process, their satisfaction increases.

This is a fact: in an environment of uncertain, unexplained, or unfair waits, satisfaction drops precipitously, especially as waits get longer. In the age of online reviews, this can quickly sink a center’s reputation. The good news is that you can dramatically improve overall patient satisfaction with your urgent care center, without the necessity of making the actual wait any shorter. You simply must understand and address the sources of patient expectations and perceptions related to the waiting experience.

References

- Maister D. The psychology of waiting lines. In: Czepiel JA, Solomon MR, Surprenant CF, eds. The Service Encounter: Managing Employee/Customer Interaction In Service Businesses. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. 1985.

- Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

- Larson R. “Dr. Queue” helps you avoid rage in line. [Talk of the Nation]. National Public Radio. November 24, 2009. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId= 120769732.

- Stevenson S. What you hate most about waiting in line. Slate. 2012 June 1. Available from: http://www.slate.com/articles/business/operations/2012/06/queueing_theory_what_people_hate_most_about_waiting_in_line_.single.html

- Camacho F, Anderson R, Safrit A, et al. The relationship between patient’s perceived waiting time and office-based practice satisfaction. N C Med J. 2006;67:409–413.

- Ayers A. Improving your clinic’s wait times. Presented at: Annual meeting of the Urgent Care Association of America; March 13, 2009; Chicago, IL. Available from: http://www.alanayersurgentcare.com/Linked_Files/UCAOA_Length_of_Stay_2009_03_13.pdfStone A. Why waiting is torture. New York Times. 2012 August 18. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/19/opinion/sunday/why-waiting-in-line-is-torture.html

- Koo M, Fishbach A. A silver lining of standing in line: queuing increases value of products. J Mark Res. 2010;47:713–724.

- Raz O, Ert E. “Size counts”: the effect of queue length on choice between similar restaurants. In: Lee AY, Soman D, eds. NA—Advances in Consumer Research. Vol 35. Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research; 2008:803–804.

- Satmetrix Systems. The Net Promoter Score and system. Redwood City, CA: Satmetrix Net Promoter Community; © 2015. Available from: http://www.netpromoter.com/why-net-promoter/know

- PNC Healthcare: five ways tech-savvy millennials alter health care landscape. From a survey conducted by Shapiro+Raj in January 2015 and commissioned by PNC Healthcare. Reported in Rappleye E. 5 trends in healthcare inspired by millennials. Becker’s Hospital Review. 2015 March 23. Available from: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-trends-in-healthcare-inspired-bymillennials.html