Urgent message: One of the occupational medicine provider’s most difficult challenges is when a patient with a work-related injury or illness is judged ready to return to full duty, but the patient resists going back to work.

Max Lebow, MD, MPH, FACEP, FACPM

INTRODUCTION

This article will address the problem of difficult-to-discharge patients who resist returning to full duty when their work-related injury/illness has resolved. We will discuss the process of early identification of work-reluctant patients while monitoring them through the treatment process, and identify ways to return patients to full duty in a compassionate, straightforward way that is consistent with good medical care and recognized occupational medicine guidelines.

THE CASE

Your patient is a 28-year-old male plumbing assistant 28 days status post minor soft-tissue injury, which occurred when a coworker opened a door and struck him on his right shoulder. He completed his shift but presented the next day with 10/10 right shoulder pain. At that time, all diagnostic x-rays were negative. However, physical exam revealed tenderness and decreased range of motion secondary to pain.

The treatment plan, following American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine guidelines, was nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, physical therapy, and home exercise. Because his job duties include lifting up to 40 pounds, he was placed on modified duty.

Now, after 4 weeks, the patient no longer has objective findings of the injury. However, he continues to insist that he is unable to return to full duty due to continued severe pain, with no change from the first day of injury.

What is your next step?

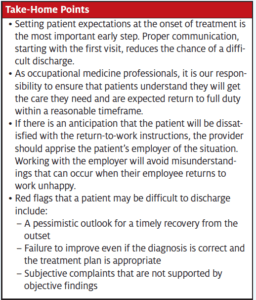

BEGIN DISCHARGE PLANNING ON THE FIRST VISIT

Reducing the chance of a difficult discharge can be mitigated by proper communication at the beginning of the case—starting with the first visit. Setting patient expectations at the onset of treatment is the most important early step. Remember, employees are bombarded by conflicting messages. Television and billboard Workers Compensation plaintiff attorneys are ubiquitous, promising that any workplace injury can turn into a financial windfall. Our job as occupational medicine professionals is to set realistic expectations so patients understand that they will get all the care they need and should return to full duty within a reasonable timeframe.

The timing of this discussion is important. Only after a thorough history and physical and completion of diagnostic testing, and after reviewing the diagnosis with the patient, should the subject of the time frame of resolution and discharge be discussed.

The occupational medicine provider who shows true empathy from the beginning of the case will have more effective communication. Building trust is essential. This sensitive discussion should be done in a reassuring and therapeutic way that lets the patient know the provider has their best interests as their guiding principle. However, making sure that the patient understands that you believe the injury/illness is self-limited, when that’s the case, is essential.

The provider may get some clues of difficulties to come even at this early stage. If the patient disputes or is overly pessimistic that they will get better in a reasonable timeline, it may represent an early red flag that you are dealing with the employee with thoughts of secondary gain from their injury.

Follow-up Care—Monitoring Recovery

Most contusions and strains will begin to resolve within the first 7–14 days. If the patient contends that they are having no improvement, it is important to review the history, physical, and mechanism of injury to assure that the diagnosis is correct. The provider should keep an open mind and be ready to seek additional information if indicated. This process may include additional diagnostic testing, such as MRI, and should include talking with the employer to find out if there are circumstances at the worksite that may affect response to treatment. A recent poor performance or conflict with coworkers or managers may help explain the patient’s reluctance to return to work.

If the patient fails to improve even though the diagnosis is accurate and the treatment plan is appropriate, especially if subjective complaints are not supported by objective findings, this may be a clue that the patient will resist returning to full duty when the time comes.

The best way to approach all patients with work-related illness/injury is through close monitoring, encouragement, and reaffirming that the patient will be better soon.

An important step to returning the patient to full duty is to review the patient’s modified duty restrictions at each visit. The goal should be a graded increase in duties at work, both to prevent deconditioning and to avoid the patient becoming “too comfortable” in their light-duty assignment. The occupational medicine provider must understand the patient’s job description and job duties to best craft a modified duty position for the injured employee.

Preparation for D-Day (Discharge Day)

Up to this point, our goal has been to first prevent, then identify, cases of the potential work-adverse patient/employee, and to closely monitor their recovery process. However, at a certain point, using medical judgment and recognized occupational medicine guidelines, the difficult task of discharging the unwilling and uncooperative patient will present itself.

Since this is part of the occupational medicine landscape, every occupational medicine provider must have a plan to deal with the situation. If there is an anticipation that the patient will be dissatisfied with the return-to-work instructions, the provider should contact the patient’s employer and apprise them of the situation. Working with the employer will avoid misunderstandings that can occur when their employee returns to the worksite unhappy.

Talking with the patient

The return-to-work conversation with the patient needs to be done in a nonjudgmental manner that stresses medical facts and deemphasizes medical judgment. The patient needs to know that it is not the provider’s sole decision that determines when the patient returns to full duty, but rather the medical facts of the case, that the human body is always healing and repairing; referencing published occupational medicine guidelines may be helpful.

If the patient still claims pain that is out of proportion to objective findings and inconsistent with the mechanism of injury, this must be acknowledged and discussed. The provider should not question whether the pain is real or imagined, but rather stress that persistent pain after a relatively minor injury is unusual.

If the patient truly is still in significant pain, there may be a cause that is not related to the original workplace injury. The provider should discuss and document in the record that continued pain is no longer considered to be caused by the injury and should be worked up by his primary care physician. Referring the patient back to the PCP for nonindustrial conditions is also an important risk management tool.

CONCLUSION

There will always be patients who will resist returning to work. These cases need not result in conflict and frustration, however. As we’ve discussed, there are specific steps that can be taken from the first clinic visit to the day of discharge that can assure that the patient receives the medical care they need, and is returned to work when it is medically indicated. The key is to use solid patient communication and medical care throughout the process.

Max Lebow, MD, MPH, FACEP, FACPM is board certified in emergency medicine and preventive/occupational medicine, and is President and Medical Director of Reliant Immediate Care Medical Group. He also sits on the Urgent Care Association Board of Directors.